Camouflage: Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, by Abbot Handerson Thayer

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.May 23rd, 2016

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Rare Book Librarian.

Can you find the peacock?

We might think that camouflage has been around forever. The ubiquitous mottling of colors, usually in shades of greens, browns, blacks and yellows, was designed to mimic elements of the natural world, such as sunlight and shadow on leaves, whether on the tree or the forest floor. So in some ways, camouflaging coloration has always been around. But the promotion of concealing coloration or camouflage as a tool for human use was proposed much more recently.

Abbot Handerson Thayer (August 12, 1849 – May 29, 1921), considered the father of camouflage, was an accomplished portrait painter of great skill and delicacy. He is far better known for his idyllic portraits of beautiful angels, women, and children than he is for the introduction of an artistic design used to conceal.

Abbott Handerson Thayer, Self-Portrait

Among his best known works are portraits of Thayer’s own family who served as models for his paintings. The Virgin, painted in 1892 – 93, shows one of his daughters, Mary, in the center, with two of his younger children, Gladys and Gerald, on either side.

Thayer’s angel portraits evoke an ethereal and dreamlike state. These paintings were designed to embrace his belief in the virtuous nature inherent in all women by placing them spiritually on a higher moral plane of existence. The first of these portraits was called Winged Figure. His daughter Mary posed for this portrait at age 11.

Thayer’s interest in concealing coloration, as he called it, in the animal kingdom began at age 15. Thayer grew up in Keene, New Hampshire, where he developed a childhood interest in the natural world. He became an outdoorsman and woodsman, hunting, trapping, and developing taxidermy skills to aid in his study of wild birds. Audubon’s book, Birds of America, a masterwork of ornithology, became one of his favorite books and he used it as a guide. Audubon too, hunted the birds he depicted, drawing them in the wild from freshly killed specimens. Just as Audubon painted the birds he discovered, Thayer too, eventually began to paint the birds he captured in watercolor.

As a student, Thayer’s formal study of painting included enrolling in the Brooklyn Art School, the National Academy of Design and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His work focused on animal and landscape painting. After his return from Paris, Thayer opened his own portrait studio and began to take on apprentice painters, one of whom, Rockwell Kent, would become a well-known author, book illustrator, adventurer and painter in his own right.

Around 1892, Thayer began studying the effects of light and shadow in the animal world. He began to appreciate the disruption of form, such as an animal’s body, through the effects of countershading. He also took note of nature’s mimics, such as insects that resemble twigs or butterflies that resemble their poisonous counterparts to avoid being eaten. His study of birds included brightly colored peacocks and flamingos. Birds that would not, at first thought, appear to be camouflaged, like a deer in the wild, but in their natural settings blended seamlessly with their surroundings.

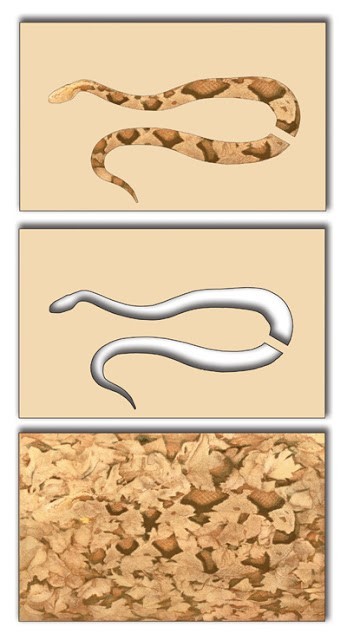

Thayer’s early work on camouflage was published as an article in a naturalist journal, The Auk. Later, continuing his studies, he published a book on camouflage, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom in 1909. His apprentice, Rockwell Kent, assisted in one of the most arresting images in the book, a portrait of a copperhead. Designed in two parts, the copperhead illustration consists of two pages, the first was a page that overlaid the illustration with a cut out section designed to reveal the snake. Once the overlayment was lifted by the reader the copperhead becomes nearly invisible in the illustration among the fallen leaves on the forest floor.

Thayer was so ardent about camouflage that he proposed its use on battleships to both the British and American military during World War I. British battleships were then painted a khaki color. Thayer proposed that the military repaint them in a disruptive camouflage pattern. Though the British opted against this move, the American military followed Thayer’s advice, painting battleships white to make them disappear on the horizon while at sea. Although battleships are no longer painted white, the groundbreaking effects of camouflage in military operations have been a staple since Thayer proposed its use in 1915.

Today, camouflage has become essential dress for hunters of all seasons, whether they’re in the woods or headed to the Mossy Oak store at the mall. It’s even made its way into high fashion in a variety of colorations, including shades of pink.

You’re invited to make an appointment to see Abbott Handerson Thayer’s trailblazing book, Concealing Coloration in the Animal Kingdom on the study of camouflage in the Rare Book Room in the West Virginia and Regional History Center – if we can find it . . .

Sources:

Abbot Handerson Thayer: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abbott_Handerson_Thayer

Peacock image: http://www.galaide.org/2006/02/05/

Thayer self- portrait: https://xliang1.wordpress.com/2012/09/19/snite-art-museum-analysis-of-self-portrait/

Winged Figure image: http://www.amylind.com/blog/216

Copperhead illustration image: http://camoupedia.blogspot.com/2011/03/henry-adams-on-art-and-camouflage.html