It's Green-up Time: the Arrival of Spring and Louise McNeill's The Milkweed Ladies

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.March 23rd, 2017

Blog post by Lori Hostuttler, Assistant Director, WVRHC.

As of Monday, spring is officially here! Every year when the time changes and we have evening light, I look forward to blooming buds and the appearance of leaves on the trees, also known as “green-up time.” I was not familiar with this colloquialism until I read poet Louise McNeill’s memoir, The Milkweed Ladies. McNeill describes all the activity that took place on the farm just before and during springtime in the chapter, “Green-up Time.” It is nostalgic and beautiful, revealing a routine unknown to most in our modern times.

“Soon after sassafras time, it was green-up time, with the first shoots coming up out of the ground. We watched the sprouts hopefully, for this was the time of year for Granny to go to the fields and woods to pick her wild greens, the “sallets” of the old frontier. Granny Fanny taught us all the plants, and how to tell the good greens from the bad. We gathered new poke sprouts, always being careful not to snip them too close to their poison roots; and we gathered “spotted leaf,” leaves of “lamb’s tongue,” butter-and-eggs, curly dock, new blackberry sprouts, dandelions, and a few violet leaves.” — The Milkweed Ladies, page 45.

“Green-up time was also ramp season, but Mama wouldn’t let a ramp come into the house, for the ramp is a vile-smelling wood’s onion whose odor, like memory, lingers on. Some of our neighbors and cousins hunted ramps every spring and carried them home in gunnysacks to boil and fry. In the spring down at school, the teacher would sometimes have to throw the windows wide open to air out the smell of ramps, wet woolen stockings, and kid sweat.” — The Milkweed Ladies, page 46.

“When we saw our first dandelion, we could take off our long winter underwear. When we saw our first bumblebee, we could go barefoot.” — The Milkweed Ladies, page 48.

West Virginia Poet Laureate Louise McNeill (1911-1993) was born on her family’s farm on Swago Creek in Pocahontas County, West Virginia. Her ancestors had lived and farmed there since 1769 and her connection to the land, people, and traditional folkways entered deeply into her writing.

“Until I was sixteen years old, until the roads came, the farm was about all I knew.” Louise McNeill, The Milkweed Ladies, page 5.

McNeill achieved success early in her career with Gauley Mountain, a collection of poems that describe Appalachian life through rich characterizations and natural language. She published poems throughout her life was also a teacher of history and English at West Virginia University, Potomac State College, Concord College, and Fairmont State College. In 1939, she married Roger Pease and is sometimes identified with his surname. Governor Jay Rockefeller appointed her as poet laureate in 1979 and she held the title until her death in 1993.

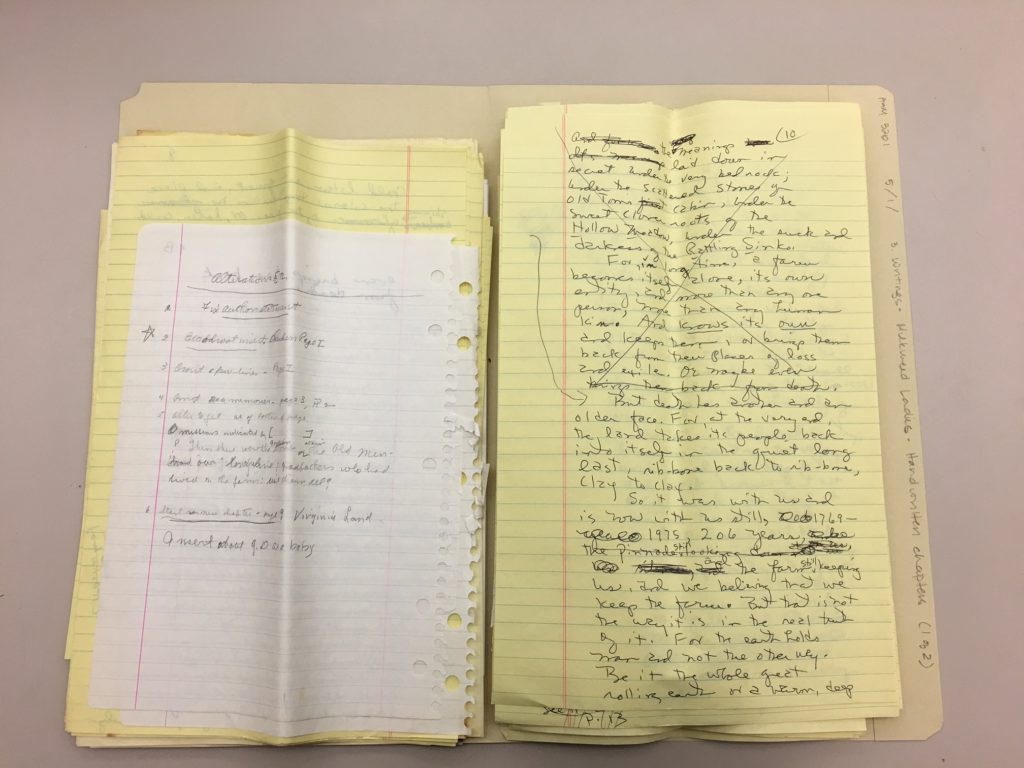

The West Virginia & Regional History Center holds Louise McNeill’s papers (A&M 2215 and A&M 3201). These collections include correspondence, photographs, and literary manuscripts. Among them are handwritten and typescript versions of The Milkweed Ladies.

From A&M 3201. The handwritten text at the bottom of the page on the right appears on page 5 of The Milkweed Ladies edited slightly more:

“Still it was with us, and is with us still, over two hundred years and nine generations of the farm keeping us, and we believing that we keep the farm. But that is not the way it is in the real truth of it, for the earth holds us and not the other way. The whole great rolling earth holds us, or a rocky old farm down on Swago Crick.”

The Milkweed Ladies is Louise McNeill’s only work of prose and turns out to be one of my favorite books. Although it is autobiographical, it is still poetic and profound. I savor it just as I cherish “green-up time” every year.

A more detailed biography and additional items from the McNeill manuscripts collection are available in this blog post from 2014: Remembering Louise McNeill Pease.