A Two-Faced Villain: John J. Davis and the Political Ideology of the West Virginia Statehood Movement, 1861-1863

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.April 17th, 2017

By Casey DeHaven, Graduate Assistant, WVRHC.

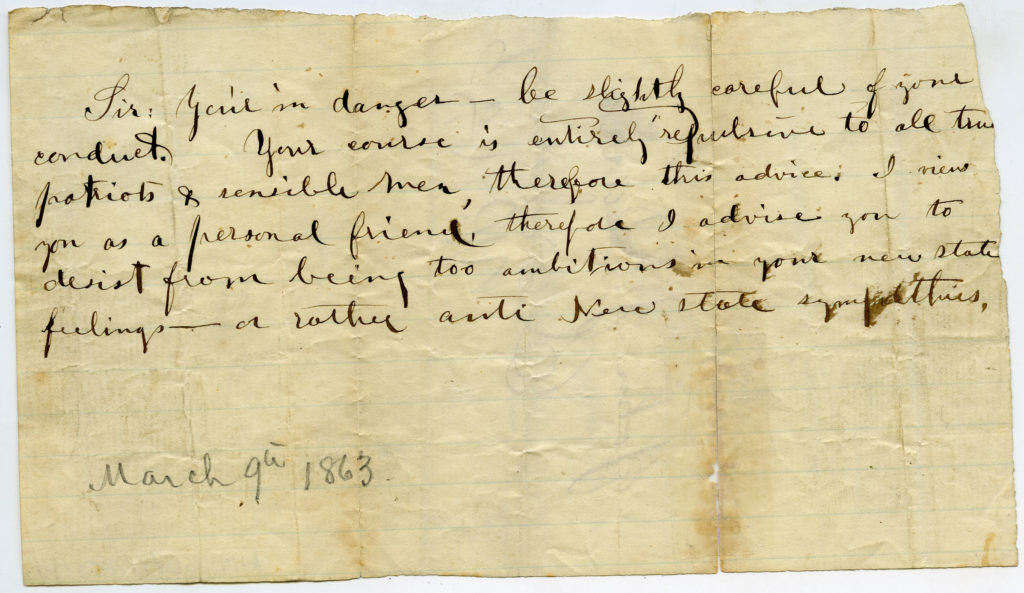

In March 1863, an anonymous author penned a foreboding letter to Harrison County delegate John J. Davis, warning the politician that his opposing stance on the West Virginia statehood movement was not well received among his constituency. “Sir, you’re in danger…your course is entirely ‘repulsive’ to all true patriots & sensible men…I advise you to desist from being too ambitious in your new state feelings – or rather anti-new state sympathies.”[1] Conceptualizations of loyalty during the West Virginia statehood movement became incredibly skewed as politicians and their constituents struggled to balance law and reason with moral principles. The movement created a fire storm that forced western Virginia citizens to redefine democracy, which consequently became so convoluted in nature that politicians at the helm of the movement began to lose former constituents and even turn on one another.

For politicians like Clarksburg native John James Davis, the movement toward statehood resulted in such a complex relationship between private and public ideals that the binding of the two were nearly untenable. In a region where Unionism was linked to pro-state sentiments, virtues such as loyalty became synonymous with being a Unionist. Any rebuttal against the new proposed state of West Virginia was subsequently deemed treasonous. For John J. Davis, his “anti-new state sympathies” became a rallying cry among his constituents who began to feel abandoned and misled by their representative.

Undated portrait of John J. Davis

At the onset of 1861, Davis, a former lawyer and newly minted democratic member of the Virginia House of Delegates, was confounded at the thought that his home state of Virginia could ever secede from the Union. The “southern fire” of the “secession spirit” was spreading rapidly throughout the Old Dominion after South Carolina was the first to make the bold move. Davis conceded his disgust for the looming endeavor in a letter to his future wife, Anna Kennedy written on January 23, 1861 stating that “peaceable separation is a delusion…secession means revolution and the latter is never peaceable.”[2] The controversy for western Virginia began in earnest during a preliminary meeting in Clarksburg on April 22, 1861. The First Wheeling Convention met shortly after the Clarksburg Convention from May 13-15, 1861.

In writing to Anna from Clarksburg on May 17, Davis divulged his personal feelings and opinions on the proceedings of the convention:

“You have no doubt seen the proceedings of the Wheeling Convention – I was a member of that body – Mr. [John] Carlisle’s [Carlile’s] resolution for immediate separation did not command my approval – I thought hasty action would not do. But at the proper time I believe our section of the State will be bound in self defense and abandon the East…the sentiment in the North West is pretty unanimous in favor of remaining where we now are – in the Union. We have no intercourse with the East – our commerce & trade is all with Maryland and Pennsylvania. You can form no idea of the strength of public sentiment in the N West on the question of separation…my hope & prayer is that the ordinance may be defeated & that Va. may remain one & indivisible.”[3]

Upon Virginia’s issuance of the Ordinance of Secession on May 23, the proposed Second Wheeling Convention was to meet June 11-25, 1861 to determine a plan of action for western Virginia. Though this convention arguably paved the way toward statehood, John J. Davis was one of few delegates to refuse to bend his anti-abolitionist views for the sake of separate statehood. Davis’s personal conundrum was one felt by many western Virginians at the time. Up until then, despite regional tensions and sectionalism, they had all been Virginians. The Southern traditions of honor and loyalty to their state were among the highest priorities, yet they were Virginians who had always remained loyal to the Union; a Union their forefathers had fought so hard to preserve just decades before. When Virginia heeded the call of secession, Davis and many of those in his constituency no longer knew precisely where their loyalties fell.

While Davis’s stance on slavery and statehood never changed, he still was determined to see that the new state of West Virginia functioned as a proper democratic entity. He was elected to the West Virginia House of Delegates in 1869-1870 and was then elected as a member of the 42nd and 43rd Congress from 1871-1875. After failing to secure candidacy for re-nomination in 1874, he went back home to Clarksburg where he continued to practice law until his death on March 19, 1916.[4]

John J. Davis in later years

[1] John J. Davis, (1835-1916). Papers, A&M 1366, Box 4, Anonymous letter addressed to John J. Davis, March 9, 1863, West Virginia and Regional History Center, Morgantown, West Virginia.

[2] John J. Davis, (1835-1916). Papers, A&M 1366, Box 1, Davis letter to Anna Kennedy, January 23, 1861, West Virginia and Regional History Center, Morgantown, West Virginia.

[3] John J. Davis (1835-1916). Papers, A&M 1366, Box 4. Letter from Davis to Anna Kennedy from Clarksburg, May 17, 1861, West Virginia and Regional History Center, Morgantown, West Virginia.

[4] John James Davis. “Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, 1774-Present”, accessed April, 2016, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=D0.