Broadsides in the History Center

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.June 1st, 2018

Blog post by Jane Metters LaBarbara, Assistant Curator, WVRHC.

The way people communicate is evolving along with technology. Today, we have event pages on Facebook to alert friends and customers to upcoming activities, and blog posts and newspaper editorials on the web to share our political feelings. What filled these communication needs before the internet? In some cases, the answer was broadsides! A broadside is “a single sheet with information printed on one side that is intended to be posted, publicly distributed, or sold” (according to the Society of American Archivists). The WVRHC’s broadsides collection includes posters, handbills/flyers, and other types of advertisements and announcements.

Speaking of the internet, not all of the WVRHC’s glorious collections are available on the web. The broadsides collection is not available online, but it is partially cataloged in the card catalog we have at the Center. The broadside catalog cards are arranged in chronological order, from the 1770s-2007; beyond that, we have some yet-to-be-cataloged broadsides for intrepid researchers to explore. Some of our broadsides are originals and some are facsimiles. Below are a few examples to give you an idea of what this collection contains.

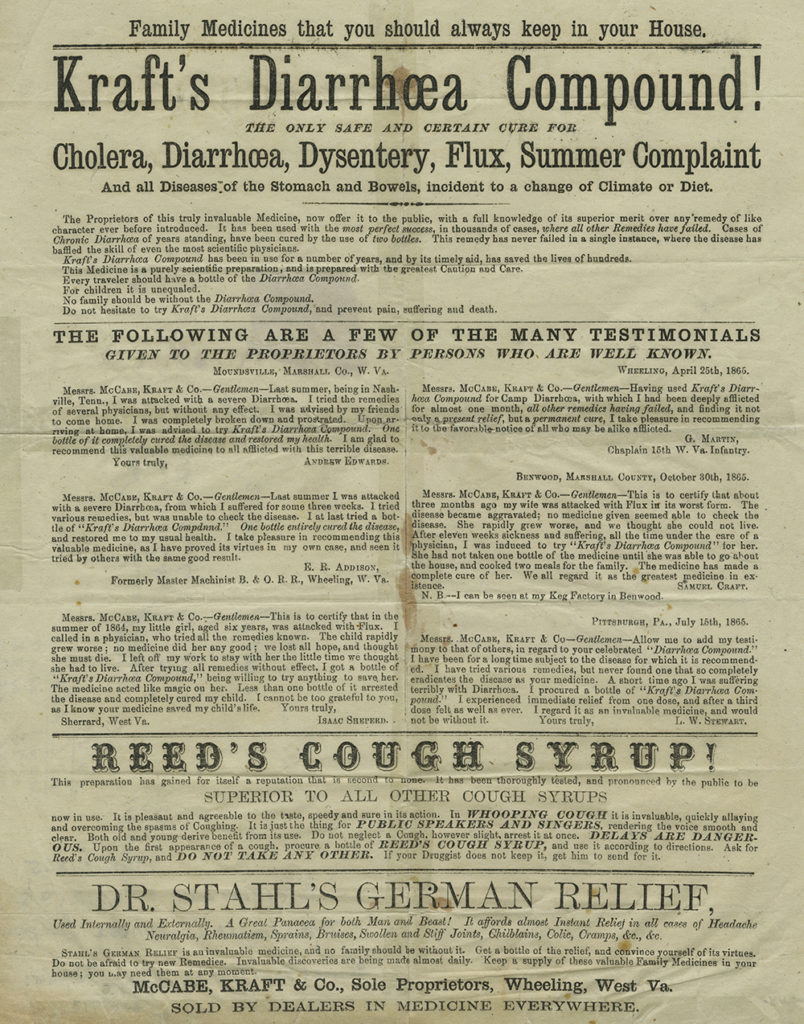

More than 60 of the broadsides dating from 1860-1865 have been scanned, most of which pertain to either the Civil War or West Virginia statehood. One of the few that pertains to neither subject is this one from 1865, which demonstrates how medicines and cure-alls were once advertised. I especially enjoy the text about “Dr. Stahl’s German Relief”–it works inside and out, for humans and animals, and helps everything from nerve pain to gas. This kind of advertisement for medicines wouldn’t fly today, but this broadside reminds me of products advertised on TV that seem to do it all (“But wait! There’s more!”).

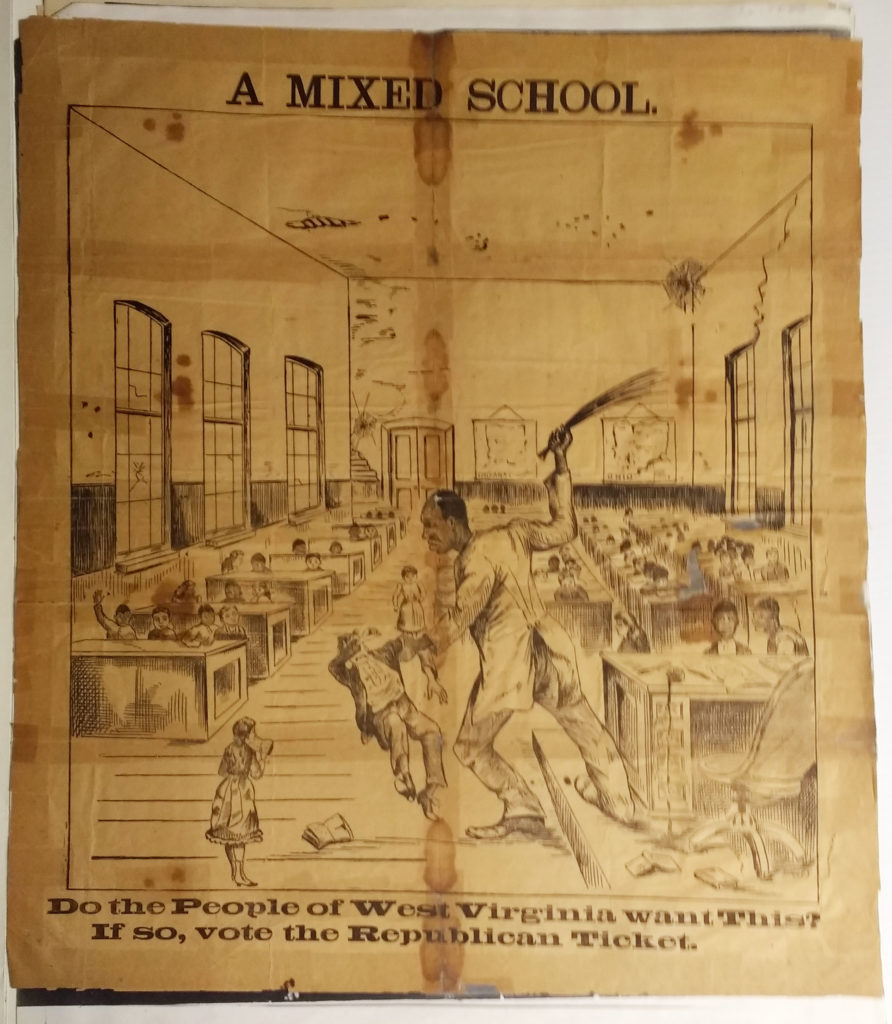

This broadside surprised me, both in its graphic depiction of the beating of a white child by a black teacher, and by the date, 1880, which is recorded in pencil on the reverse. While the image and sentiments behind it are disturbing, this is a part of West Virginia’s past. We can draw parallels between the racism and fearmongering in this old broadside and similar sentiments shared on social media and reported by news outlets today.

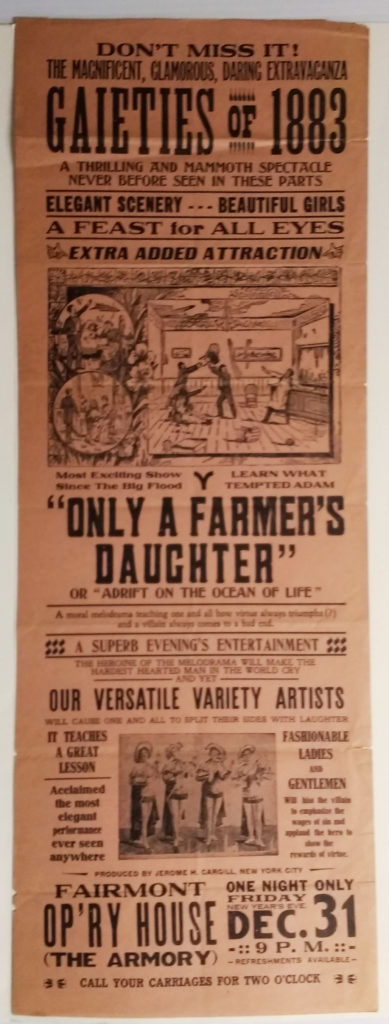

This 1883 broadside advertises a show coming to Fairmont, which apparently included a wide variety of entertainment. It sounds like an exciting way to spend New Year’s Eve–“learn what tempted Adam” and “the heroine of the melodrama will make the hardest hearted man in the world cry” are interesting selling points.

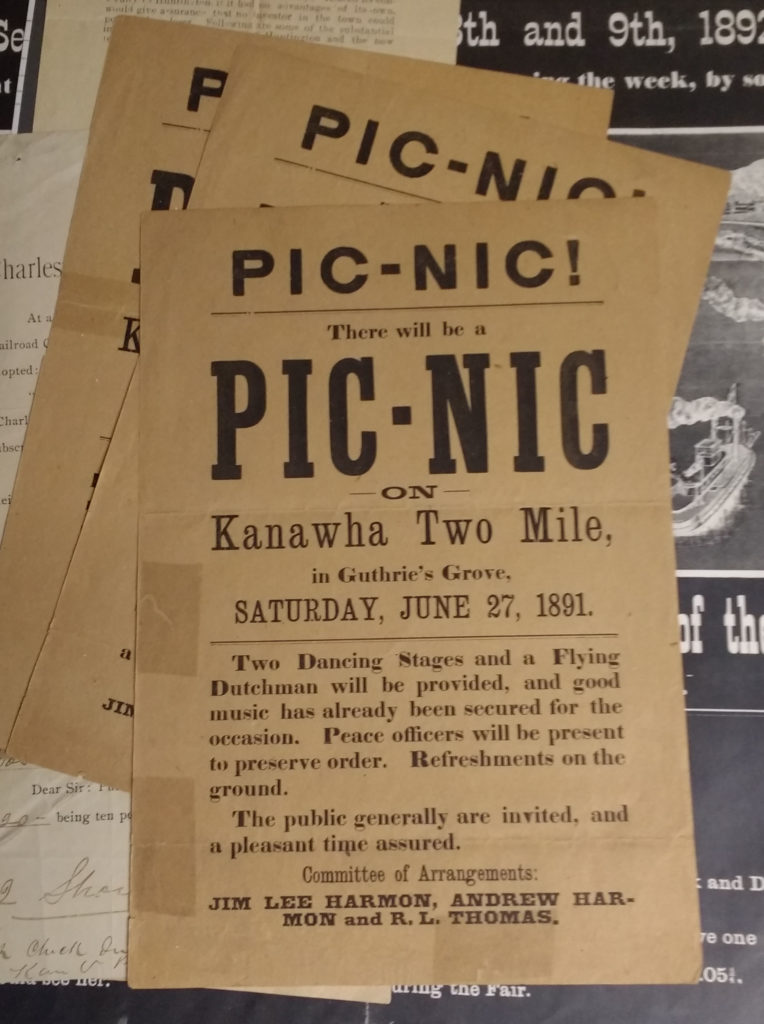

This 1891 broadside is another typical, and more tame, example of how events were advertised. I am not sure what a Flying Dutchman is in this context, but it was advertised as “a pleasant time.” [Editor’s Note: After an inquiry on the Center’s Facebook page, a department-wide email, and some quick research, we have determined that in this context, “Flying Dutchman” mostly likely refers to a type of Polish polka dance. If you have additional insight about this, please reach out to us!]

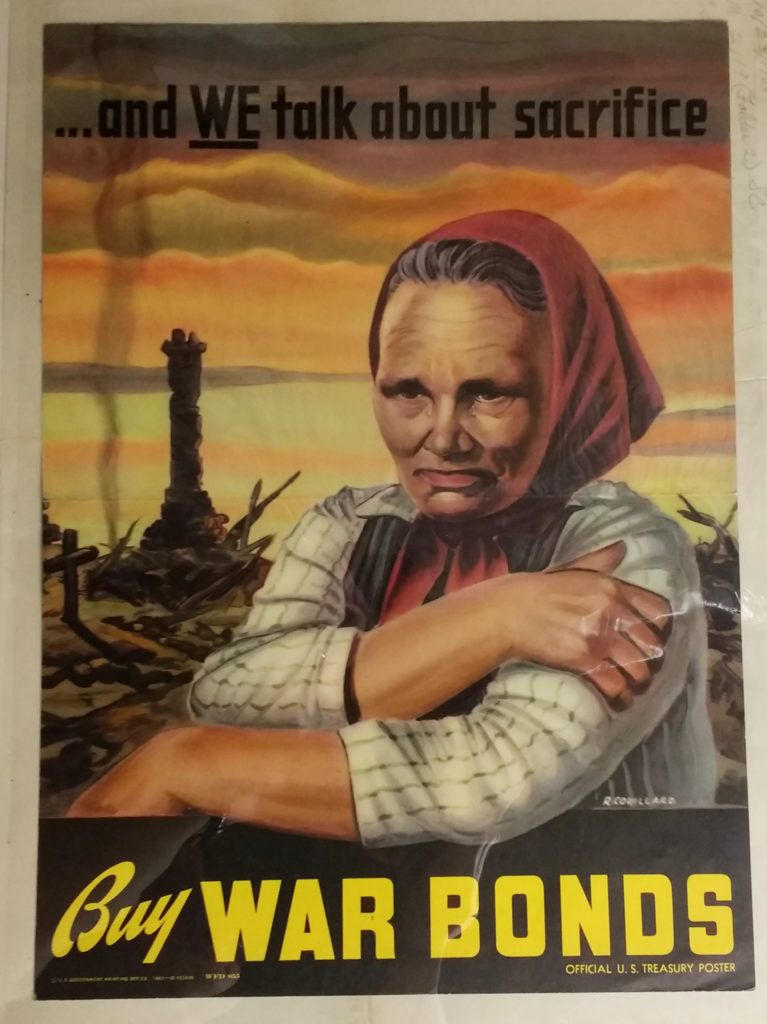

This broadside is in full color, from 1943, encouraging us to buy war bonds by making us think about our European comrades who had to deal with destruction firsthand.

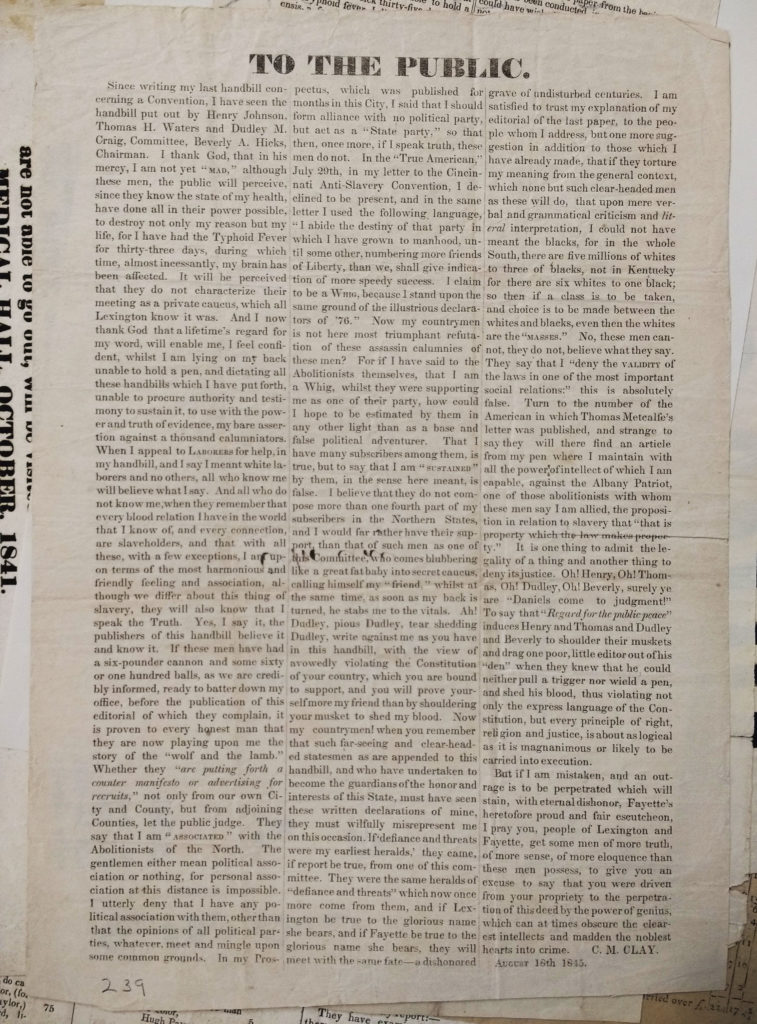

The Center also has broadsides scattered throughout our archives and manuscripts collections, with one large group of broadsides in A&M 1209, the John M. McCalla Papers. The collection includes about 258 broadsides that mostly pertain to Kentucky, especially Lexington, from the 1790s through the 1840s. These broadsides were also cataloged onto cards, which are organized by subjects, ranging from the formation of Lexington to local feuds and duels to local entertainment.

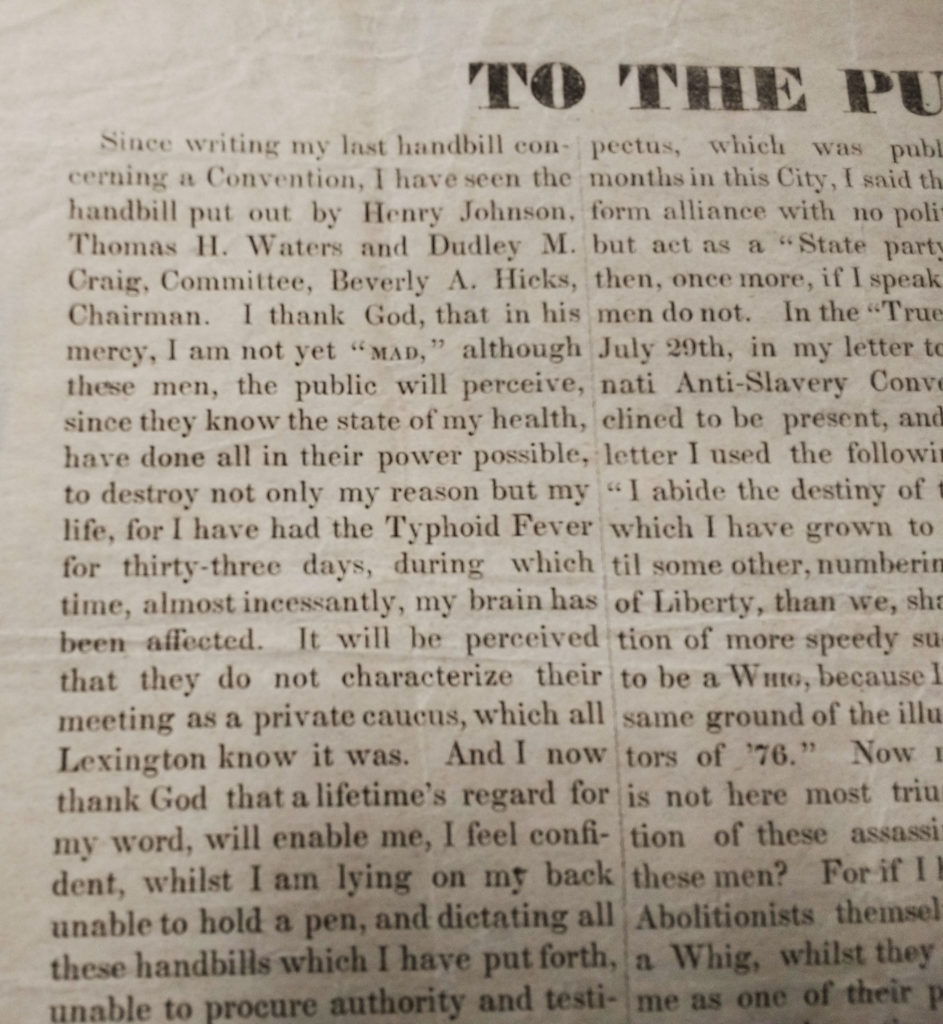

One of the many handbills in the McCalla broadsides is from Cassius M. Clay (the Kentucky politician, not the boxer). In this handbill, he defends himself from accusations made in someone else’s handbill. While the language is not quite what we’re used to today, it reads like a combination between a newspaper editorial and a modern-day political tweet (albeit significantly longer). Below is a closer view of the beginning of the handbill, where he refutes his opponents’ suggestion that he is mentally unwell and begins to defend himself against the assertion that he was “associated” with the “Abolitionists of the North.” Clay was about 34 years old when he wrote this, and already known for his anti-slavery opinions.

These and many more broadsides are available to view in the Center. Any staff member can point you to the card catalog where many of the broadsides are described, and we can also make available the boxes of undescribed broadsides. They touch on a vast array of subjects and opinions, and they have a lot to teach us about who we were and how we communicated.