Before the Holiday: Remembering Child Labor in West Virginia

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.September 5th, 2018

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Assistant Curator for WV Books & Printed Resources & Rare Book Librarian

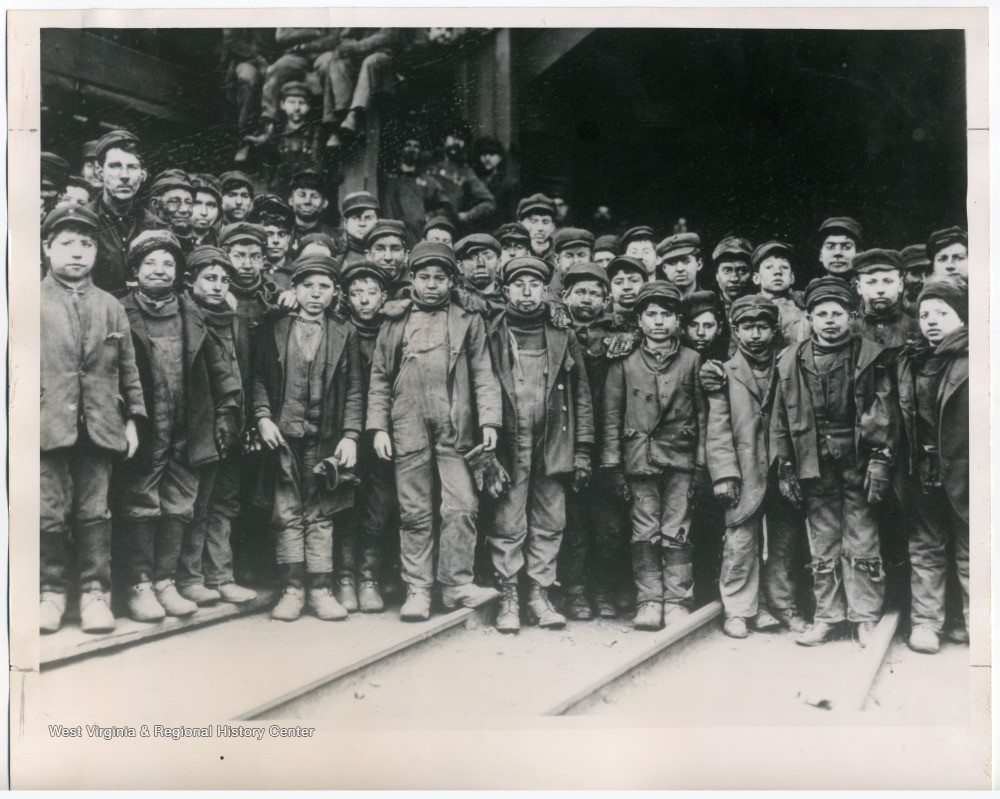

Faces smudged with coal dust, clothing torn and dirty, hands cut and bruised from reaching down to pick slate from chutes beneath them; this was the fate of the young boys who worked in the mines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and elsewhere in the United States.

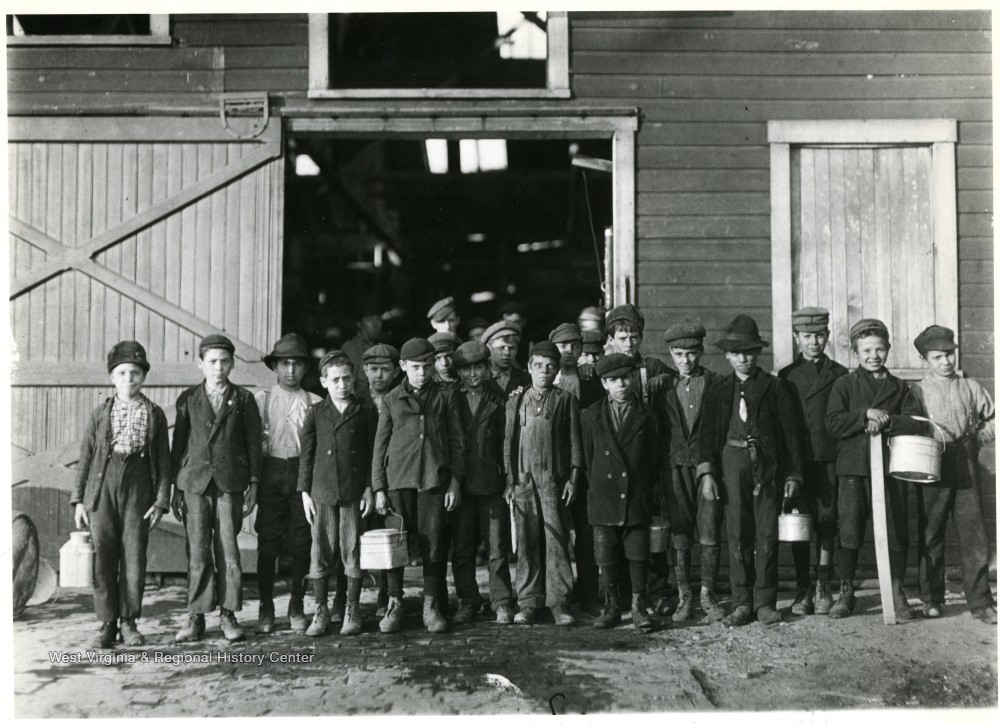

The photo above, captioned “No Time for School in 1911,” portrays a group of young boys, aged nine to fourteen, at the end of their ten-hour shift in a West Virginia coal mine. The “breaker boys” pictured here worked long hours, the same shifts as adults, six days a week, and earned less, an average of 50-75 cents an hour, because they were children. It was photographs like these, of young children with dirty faces, scarred hands, and bent backs, that led to the passage of effective child labor laws to prohibit the exploitation of young workers in mines, mills and factories throughout the United States.

Lewis Hine, (1874 – 1940) one of the most prominent photographers of the Progressive Era, dedicated much of his career to capturing scenes like this one. A sociologist, Hine had a long history in photography. During his years as an educator, Hine used photography as a means to teach his students. After photographing immigrants as they arrived at Ellis Island, Hine realized that photography could also be used to document current issues thereby providing images to support argument. After a stint with the Russel Sage Foundation, Hine joined the National Child Labor Committee, (NCLC) where he spent over a decade photographing children at work. A great deal of his time was spent in West Virginia photographing children working in coal mines and glass factories. During his years with the NCLC, Hine’s photographs developed into an extensive body of work documenting child labor. Hine’s career as a sociologist and educator, coupled with his interest in photography, ultimately changed the way people viewed child workers and influenced legislation.

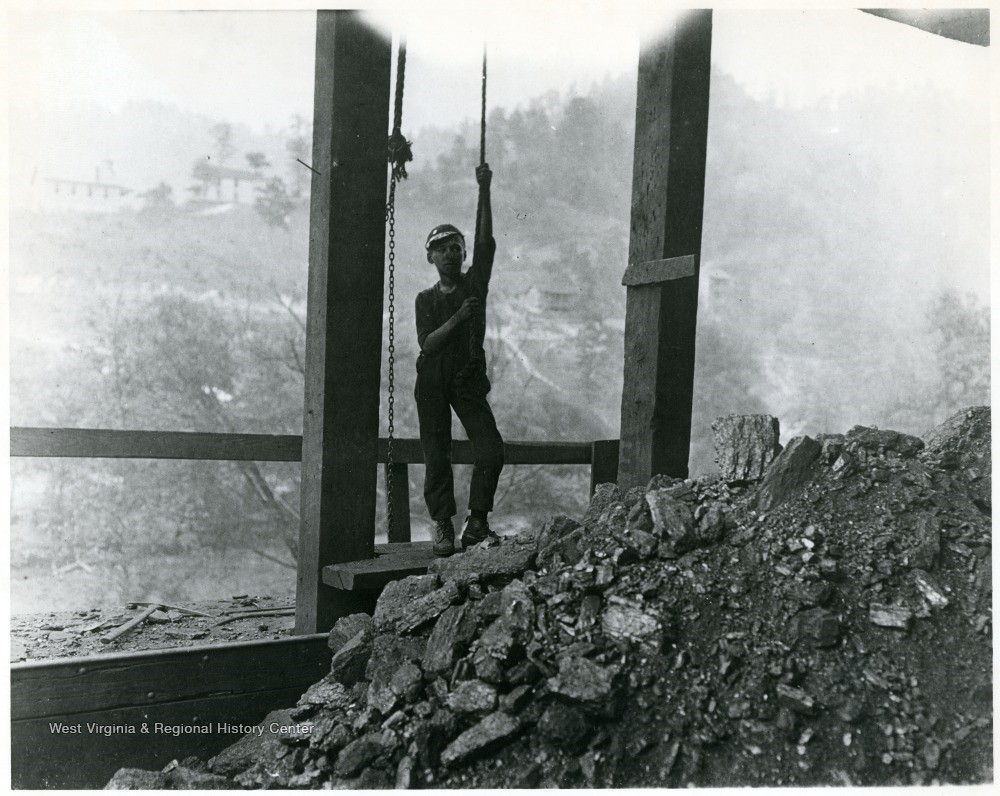

Small boy running the trip rope, Welch Mining Co., Welch, W. Va. Credit National Archives 102-LH-70. Photo by Lewis Hine.

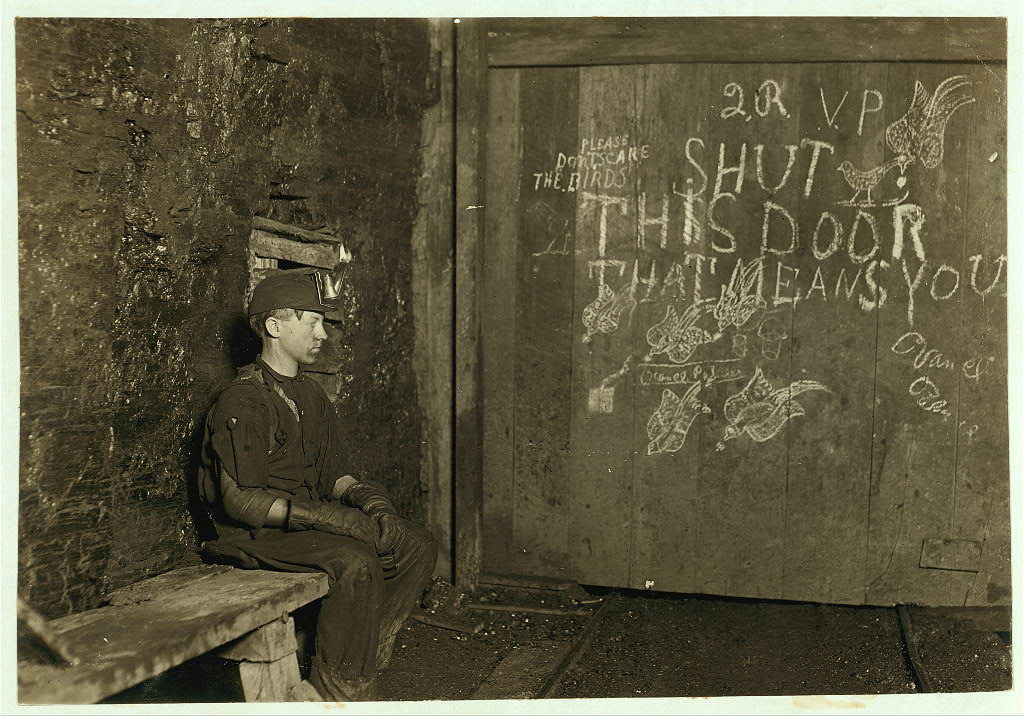

When viewing Hine’s images today, we see an undeniable quality that is evocative of their era. They are often compelling and also deeply moving, like the one below. The young boy in this undated photograph has been identified as Vance Palmer, believed to be about 15 years old. He worked as a door boy or trapper boy in an unnamed coal mine located in Harrison County. Lewis Hine’s caption for this photo reads:

“Vance, a Trapper Boy, 15 years old. Has trapped for several years in a West Va. Coal mine. $.75 a day for 10 hours work. All he does is to open and shut this door: most of the time he sits here idle, waiting for the cars to come. On account of the intense darkness in the mine, the hieroglyphics on the door were not visible until plate was developed.”

This photo of Vance Palmer was taken by Hine one hundred and ten years ago, September 1908. Originally, when Hine wrote his caption, he failed to include Vance’s last name. It went unknown for 101 years until Joe Manning, an author, historian, and genealogist in Massachusetts, discovered this image on the Library of Congress website. Intrigued, he was able to identify Vance from the initials he saw among the birds and notices Vance drew on the mine door, described by Hine in his caption as “hieroglyphics.” You can see his initials, V.P., in the upper right hand corner of the photograph.

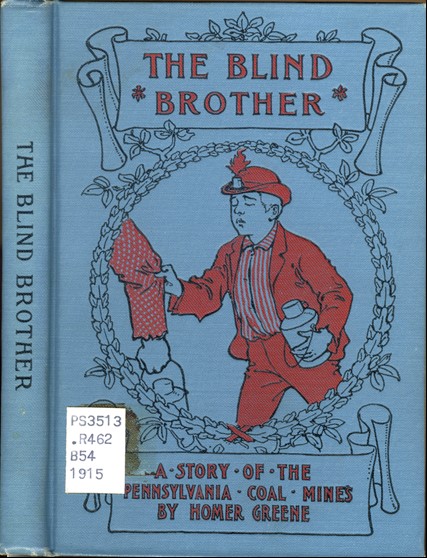

Stories reflecting real life, such as this one, were translated into fiction and made available to children who were educated and had the ability to read. Homer Greene’s story, The Blind Brother: A Story of the Pennsylvania Coal Mines, centers around two brothers, Bennie and Tom. Bennie, the younger of the two, is blind, yet he can still work in the mine as a door boy and make a few cents a day in order to help support his family. Although the focus of the book’s cover is on Bennie, we can see him clutching his brother’s elbow as he leads him to his job, then taking him home again when the working day is at its end.

Books also told stories about the “breaker boys,” or “slate pickers.” Two books that explored the lives of young boys working in coal mines are pictured below, Tom Martin: The Breaker Boy (1926) by R.P. Phelps, and Ben Burton, The Slate Picker, by Harry Prentice (1888). Stories like these illuminated the real life travails of working children.

Although Tom Martin: The Breaker Boy, is a work of fiction, the story was all too representative of reality. The difficult life led by children working in the mines is explored through the character of Tom Martin, who takes his first job as a breaker boy at the age of ten. From this job, Tom moves to his next position as a Fan Boy, an extremely important job requiring him to keep the fans moving in order to circulate air within the mine. To maintain the constant rotation of the fans was a manual job and it would be exhausting. Failure to keep the air moving meant that the air quality would suffer; gas would be allowed to accrue in the mines resulting in an explosion. When Tom is a little older he is given the job of coal pusher, keeping the coal moving down the chute as fast as the miner with him could work it out. When he is not quite twelve years old, Tom is employed on the rotary hand screen. The rotary screen was used to sort coal after it had been brought out of the mine. His next job is driving the mules hauling coal along the mine gangway. At thirteen Tom was hired as a miner’s helper. It is at this job that Tom learns how to mine, becoming familiar with all the miner’s tools and their uses, and how to make a cartridge for blasting. In Phelps’ story, Tom reaches the top of his profession, working as a miner, at the age of 14.

This was the typical work pattern of children in the mines. A boy would spend his entire life, moving from job to job within the mine system, finally becoming a miner as an adult.

The story of Ben Burton, the Slate Picker, relates the tragic life of Ben, the son of David Burton, a miner who was injured in a blast in the Wyoming coal region of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. As the story unfolds, Ben bravely shoulders the burden of the family’s upkeep and joins the ranks of the breaker boys. Prior to his father’s death, his parents hoped he wouldn’t have to work in the mines. Ben had been allowed to go to school, where he proved to be a good student. This point is established when he publishes a poem of his own composition in the local newspaper, the Anthracite Weekly Miner. But as with all hopes and dreams in the coal fields, it was not to be. Ben, too, would spend his life in the mines.

Several factors led to the alignment of forces to legislate child labor: the tenets of the Progressive Era, (1890s – 1920s) which supported social activism and political reform, the use of photography as a documentary tool, and government legislation to prohibit the abuse of child workers.

One of the challenges facing the proponents of child labor regulation can be found in a 1905 article published by the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science by Owen R. Lovejoy.

In his article, Lovejoy reported one of the difficulties facing legislation was the disparities that arose between states with similar industries. For example, Lovejoy points out that the age of a child can determine how long and on what days the child may work which varied by state. He cites a study of the glass industry in Western Pennsylvania, Eastern Ohio, and the panhandle of West Virginia regarding child age limits. In this study it was found that Ohio had the highest age limit, fourteen, for working children. From this high point the limits decrease to thirteen in Western Pennsylvania and twelve for West Virginia. The study further found Ohio prohibited children under sixteen from working at night, Pennsylvania permitted children of thirteen to work at night, while West Virginia allowed children as young as twelve to work at night. When a manufacturer was confronted with age limitations for night work, he threatened to move his manufacturing facility to West Virginia in an attempt to avoid intended legislation.

Group portrait of boys going home from Monongah Glass Works, Fairmont, W. Va. Photo by Lewis Hine. Credit National Archives 102-LH-185.

As Lovejoy states, the study showed that legislation of child labor should be based on the broader perspective of similar working conditions rather than the local perspective of state boundaries. Looking at these photographs today, we might wonder why children were allowed to work under such conditions. The answer is a complex one, but the key word in this equation is small. Industry and manufacturing owners alike employed children as young as three years old because they were small. Their size allowed children to handle tools that were too small for adults to use effectively and they could work in spaces that were too small for adults. Poverty stricken families relied heavily on the pay earned by their children to support them. Even if the wages were small, their contribution was large. Childhood as we know it today was not guaranteed and education was largely neglected.

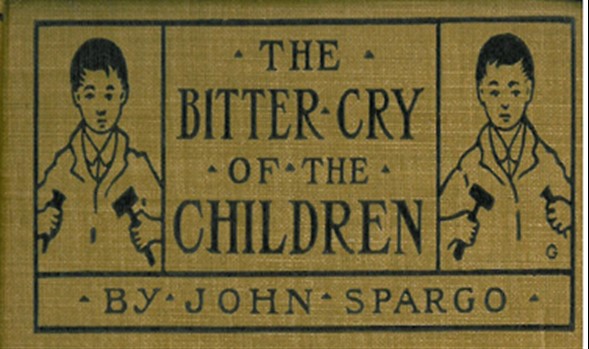

Books, such as exposés like John Spargo’s The Bitter Cry of the Children, were also credited with influencing legislation. Spargo, a reformer of the Progressive Era, wrote about the poverty faced by the American child in 1906. While Spargo’s book focused on child poverty, he recognized that poverty itself stems from a variety of causes. The cover design of Spargo’s book is representative of one of his most compelling chapters, “The Working Child.” The book’s cover portrays two little boys, tools in hand, who must work, but whose work does nothing to raise them or their families out of poverty.

Hine’s photographs, in conjunction with the social reforms of the Progressive Era, coupled with government legislation, all came together to put an end to the conditions faced by working children in the United States. If you would like to explore this subject further, please make an appointment with me, Stewart Plein, to see the books mentioned in this blog post. To see these photographs and others depicting child labor in West Virginia, please stop by the West Virginia and Regional History Center or visit the website, West Virginia History OnView: https://wvhistoryonview.org/

Resources:

Articles and websites:

- Lovejoy, Owen R. “The Test of Effective Child-Labor Legislation.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 25, Child Labor (May, 1905), pp. 45-52. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1010928 Accessed: 27-03-2018 21:14 UTC

- Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Labor_Day

- Sullivan, Ken “Holidays and Celebrations.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 17 August 2015. Web. 04 September 2018.

- Wikipedia: Progressive Era: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Progressive_Era

Photographs:

- Images of books taken by the author, Stewart Plein, Rare Books Curator, from her paper: From Hopelessness to Hope: Stereotypical Images of Children in Appalachia. Publishers’ Bindings: 1879 – 1926. Paper presented at the Thirty-Third Annual Appalachian Studies Conference, Friday, March 19 – Sunday, March 21, 2010.

- Group photo of breaker boys, boy pulling rope, and boys at glass factory from West Virginia History OnView, West Virginia and Regional History Center.

Blogs:

- Photo of Vance Palmer (1893 – 1945) and information about Lewis Hine and Vance Palmer from the blog: “Mornings on Maple Street: A Collection of Articles, Stories, Photographs, the Lewis Hine Project, and much more by Joe Manning.” https://morningsonmaplestreet.com/2014/11/26/vance-palmer-page-one/

- Mashable blog post: “1908-1911 Child Miners: The photos that helped abolish child labor in the U.S.,” by Alex Q. Arbuckle: https://mashable.com/2015/10/05/child-miners/#8ijFGl8_9Oqq

Books:

- Greene, Homer. The Blind Brother. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell & Co., ©1915. Call number: R462 B54 1915. RBR

- An audiotape of Homer Greene’s book, The Blind Brother, is available on YouTube: https://www.google.com/search?hl=en&tbm=isch&source=hp&biw=1186&bih=916&ei=oeeOW9-aA-LA0PEP_vKiqAc&q=blind+brother+book&oq=blind+brother+book&gs_l=img.12…1625.5789..7705…0.0..0.129.2134.0j18……0….1..gws-wiz-img…….0j0i5i30j0i8i30.yfQjXeRnNFA#imgrc=Jw4wJ_KCvhNauM:&spf=1536092073612

- Phelps, R.P. Tom Martin, The Breaker Boy. New York, Cupples & Leon Company [©1926]. Call number: PS3531.H38 T6 1926. RBR

- Prentice, Harry. Ben Burton, The Slate Picker. New York, A.L. Burt, [©1888]. Call number: PS2655 .P42 B4 1888. RBR

- Spargo, John. The Bitter Cry of the Children. New York, Johnson Reprint Corp., 1969. Call number: HV713 .S7 1969