Soup Beans and Archives Month

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.October 23rd, 2018

Blog post by Jane Metters LaBarbara, Assistant Curator, WVRHC.

Beans mean a lot of things to a lot of people. Growing up outside Appalachia, I remember seven-bean soups being prepared, glass jars full of artfully layered dry ingredients, and sold by church ladies for charity purposes, frequently around the holidays. When my family bought a jar, it always felt like a treat. The other bean-treat of my youth was our neighbor’s chili. I’m fairly certain that it contained multiple kinds of beans, plus a few green veggie bits, and such a good flavor. (I invite you to imagine my dismay when we moved to Texas and I was told that “real” chili contained no beans at all.)

For people across the country and across the globe, beans are a staple food. You can have baked beans, beans on toast, falafel, hummus, refried beans, red bean paste, red beans and rice, succotash, lentil soup, shiro, etc. As I grew up, I learned about and tried a variety of bean-related dishes. Then I moved to West Virginia and I heard about soup beans. Not bean soup—soup beans. Like many modern-day armchair researchers, I started my research into soup beans on the internet, but I was not satisfied. My next step was to take a look at what library resources we had on soup beans.

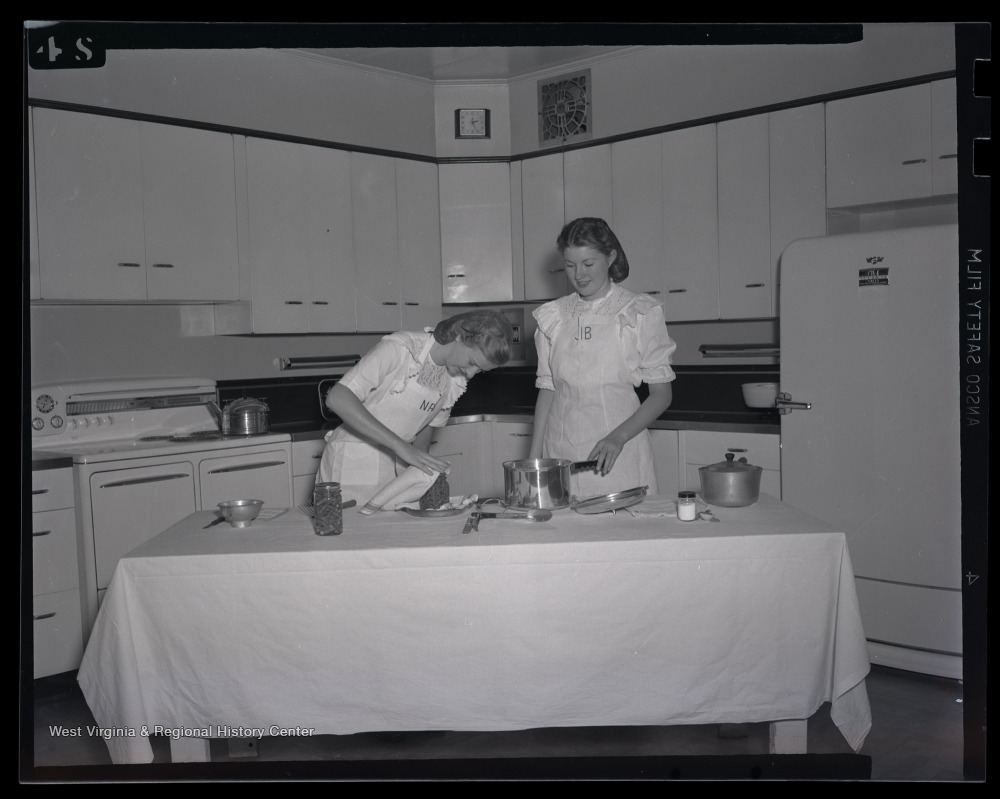

Two Women Demonstrate How to Can Beans at State 4-H Camp in Jackson’s Mill, Lewis County, W. Va.

QUICK HISTORY

A few books and articles later, I know a little more about soup beans and their place in Appalachian foodways. The most common bean used to make soup beans was historically the pinto bean (brown bean), and in some contexts “soup beans” can mean dry pinto beans rather than the soup itself. Apparently, it is usually a pork-flavored dish which can be made with as little as three ingredients: pork, beans, and water. I am told by a colleague, and books have confirmed, that soup beans ought to be eaten with cornbread, which can be crumbled into the soup beans to thicken them. A variety of other foods have been suggested as traditional sides, from wilted (“killed”) lettuce to chow chow to fried potatoes.

“Simple, traditional, and mountain through and through, soup beans are a silky smooth, pork-flavored dish of pinto beans usually free of bean soup ingredients such as peas, potatoes, parsnips, tomatoes, carrots, and celery.” (Sohn 70)

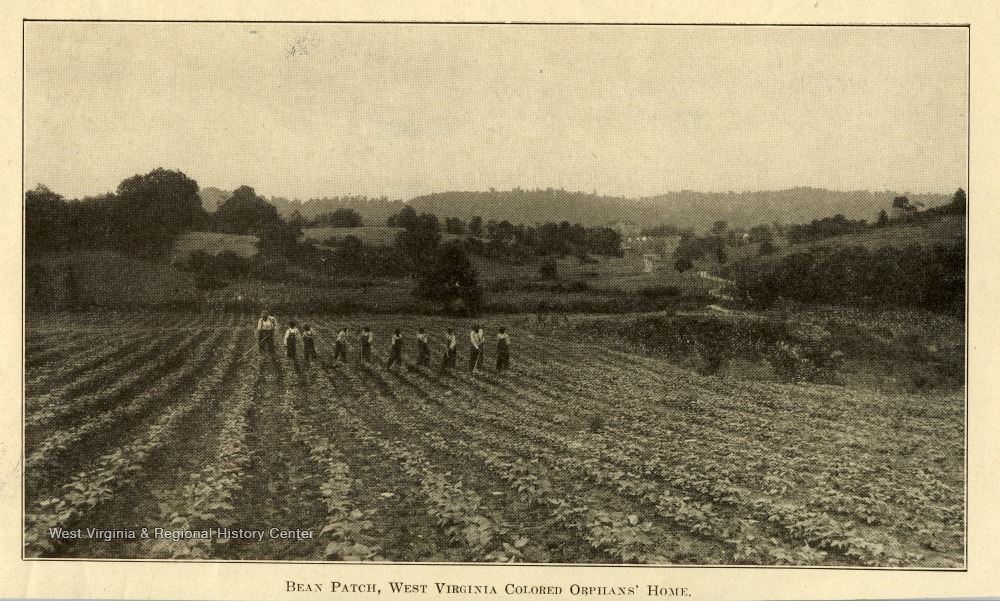

Several boys working in the bean patch at the West Virginia Colored Orphan’s Home in Huntington, West Virginia, June 1914. I do not know enough about bean plants to speculate on what kind of beans these boys are working with.

FOOD IN THE ARCHIVES

October is American Archives Month, where we celebrate the value of archives and remind people what archives have and how they can be used. From archives, we can learn what and how people ate, how they cooked, how they harvested, and how they valued and sold various foodstuffs. Materials in archives that tell us about food can include recipes, advertisements, cookbooks, oral histories, ledgers, photographs, and more. It is worth noting that, as far as images go, our descriptions are only as good as our knowledge. A researcher pointed out that some of our photos of plowing may not have accurate/specific names of farm equipment used—if anyone wants to volunteer to help us evaluate the accuracy of our farm-related photo descriptions, let us know!

This photo is titled “Horse Plough Team Harvesting Crops,” but I am not sure if that’s really what is happening here.

I quickly searched for mentions of beans or soup beans in our archives, and I haven’t found anything yet. I have several theories about this, which relate to important truths about archives. First, people donate what they think is worth donating—people aren’t likely to donate things they want to pass on to the next generation (this can include recipe cards about soup beans) or things they don’t think are important enough. Second, the things that are solicited by archivists and described in archives tend to reflect what archivists think will be important and useful to tell our history to researchers of the future—basic recipes of staple foodstuff may exist in our collections but may not be called out in the finding aids.

As you can see, I didn’t have much luck with my research on soup beans in the archives. If you find yourself hitting a wall in your research, too, do not despair. Ask an archivist! Sometimes we can help people understand why their research isn’t yielding results, and how to get answers to their questions in new and different ways.

RECIPES

Even once I moved my search from the History Center’s archival collections to our collection of professional and community-compiled cookbooks, it was harder than I thought to find recipes for soup beans. While I didn’t check every cookbook, a review of more than ten likely contenders brought up very few results. I assume that this is because a lot of people living in West Virginia in the past half-century already knew all about soup beans. Why submit a recipe for something almost as simple and common as buttered toast when you could share your special recipe for deer bologna or shattered glass salad? Alternatively, it could be that soup beans are found in more cookbooks than I thought, just not in the soup section—in one book, it was listed in the ”Vegetables and Side Dishes” section, in another it was in with “Starchy Vegetables.” A request from me to all future cookbook creators: put a recipe index in the back! Below I have copied three recipes, two for soup beans and one for soupy beans.

Soup Beans (from Appalachian Home Cooking, 2005, p. 222-223)

Preparation Time: 10 minutes

Start to finish: 20 to 24 hours

Yield: 10 to 12 servings

1 pound dried pinto beans, washed and picked over for pebbles

7 cups water

8 ounces salt pork or 2 smoked ham hocks to equal about 1 pound

Step 1. Soak the beans in the 7 cups of water overnight. Use a glass or china container and do not drain.

Step 2. Place the beans and all the water in a saucepan and add the pork. Simmer covered for 6 to 8 hours. Add water as needed to keep the beans covered. When cooked, the beans hold their shape but are soft throughout. Remove the pork and serve it as a side dish.

Step 3. If desired, thicken the broth by boiling it down and mashing in some cooked beans, or puree a cup of the beans in a food processor and return the puree to the soup.

Soup Beans (from Victuals, 2016, p. 154)

“The smell of the first winter pot of soup beans simmering on the back of the stove filled our house with warmth and a sense of great comfort.”

Serves 8

1 pound dried pinto beans

½ pound salt pork

1 small onion

1 garlic clove

2 teaspoons salt

The night before, sort the beans to make sure there are no small rocks, twigs, or clumps of dirt. Rinse them well in a colander, then put them to soak in a big bowl with cold water at a level a couple of inches higher than the beans. Leave them at room temperature overnight.

When you are ready to cook, skim off and discard any skins or funky beans that have floated to the top. Put the beans and any soaking water into a heavy pot with a lid, and add more water to reach about an inch above the beans. Nestle the salt pork into the beans.

Peel the onion and garlic clove, and nestle them into the beans as well. Bring the water to a boil on high heat, then turn it to a simmer and cover the pot. Cook the beans at a simmer until they are very soft and tender. Depending on the age, and therefore the dryness, of the beans, this can take from 1 to 2 hours.

Remove the seasoning meat, the onion, and (if you can find it) the garlic from the pot and stir in the salt. Allow the beans to simmer, covered, for another 15 minutes or so to let the salt soak in. Taste, and add more salt if needed. Serve hot. I like to crumble my cornbread in the bowl and pour the beans over it.

[Both of the above recipes were shared along with variations for those who don’t want to use pork in their food, which amounts to adding oil and spices—vegetarians rejoice!]

Soupy Beans, by Mary Hicks (from Farm Women’s Cookbook, 2003, p. 33)

1 lb. dried white beans, such as northern, navy or cannellini

1 ham hock, split or about ½ lb. smoked pork necks, ham bone or ham

1 med. onion, halved

Salt and freshly ground pepper

Water

Place the beans in a medium saucepan and cover with 3 inches of cold water. Soak overnight (or as a shortcut, simply cover beans with cold water and cook over high heat just to the boiling point; remove from heat, cover and let sit for 1 hour). Drain the beans and return to the pan. Cover with 2 inches of cold water. Add ham hock and onion and bring to a boil over high heat. Reduce heat, cover and simmer until beans are very tender. (Some of the beans will fall apart and form a thick sauce.) This will take anywhere from 1 ½ to 3 hours, depending on the age of the beans. (If desired, remove ham hock from beans. Pull off meat, cut it into bits and return meat to beans. Discard bone and gristle.) Taste beans and adjust seasonings with salt and plenty of pepper. Soupy beans are best served hot with Leroy’s pickled cabbage. The beans will keep, and even improve, for several days in the refrigerator.

…AND MORE

My research into soup beans my be done for now, but Archives Month is not over yet. Archives are living things, made up of the ever-increasing history that we put into them. In celebration of Archives Month, I encourage you to think about the histories that you have to pass on, whether that includes oral history, photos, old business papers, or a box of Appalachian recipe cards. How to you want these things to be remembered? Who do you want to have access to those stories? This could be your month to teach your nephews how to make memaw’s soup beans, to donate your grandpa’s business records to an archive, to label all your family photos, or even to shred those tax returns you’ve saved since the 1980s. Happy Archives Month!

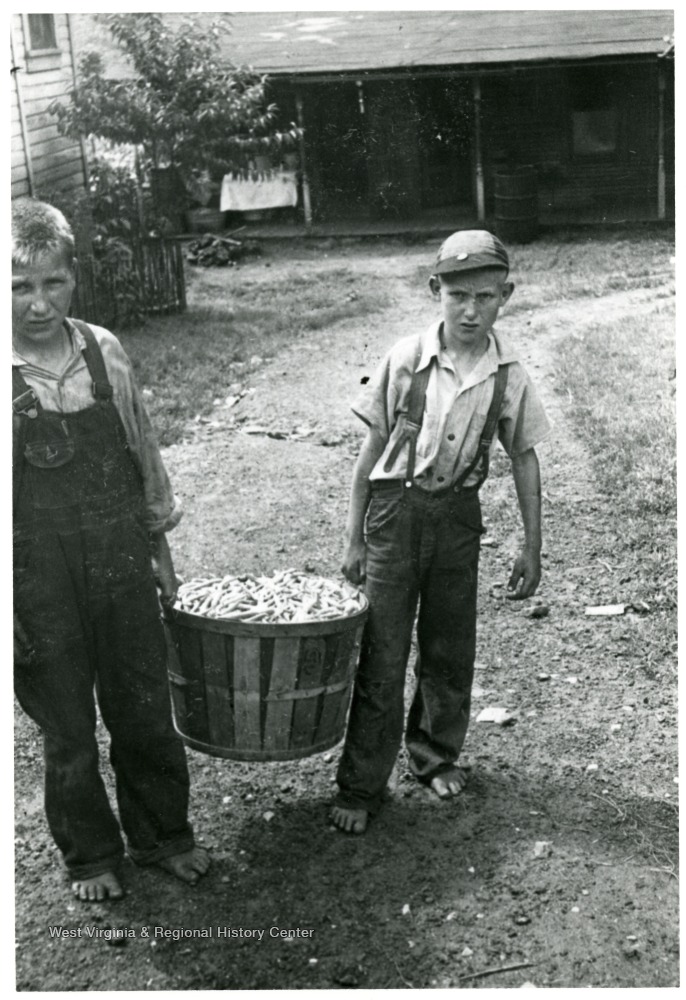

Scott’s Run Boys Carrying Beans

Side Note:

During my research, I found an article that might be of interest to those who are more food-science oriented:

Bonorden, William R, and Barry G Swanson. “Thermal Stability of Black Turtle Soup Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris) Lectins.” Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, vol. 59, no. 2, 1992, pp. 245–250., doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740590216.

Sources Used:

Helvetia Farm Women (Helvetia, W. Va.). Farm Women’s Cookbook: Helvetia Family Favorites. Morris Press Cookbooks, 2003.

Lundy, Ronni. Victuals: An Appalachian Journey, with Recipes. Clarkson Potter, 2016.

Sohn, Mark. Appalachian Home Cooking: History, Culture, and Recipes. University Press of Kentucky, 2005.