Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.May 21st, 2019

Blog post by Jane Metters LaBarbara, Assistant Curator, WVRHC

Please note, this post mentions the suicide of a fictional character.

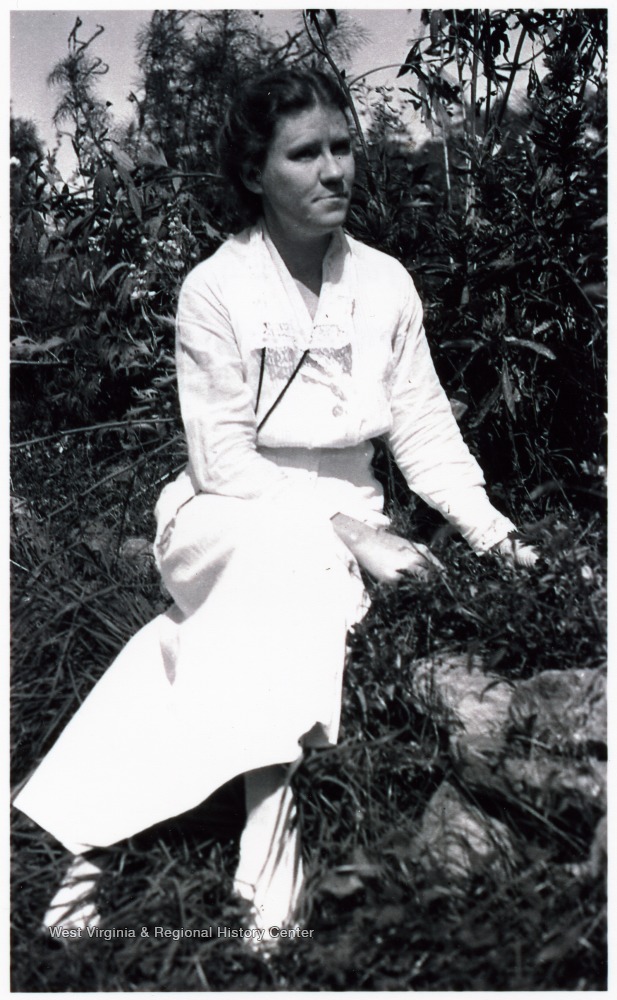

While reprocessing the collection of Margaret Prescott Montague, a West Virginia-born author, I discovered that one of her stories was made into a movie when I found a large folder of clippings about it. I wanted to know more about what this White Sulphur Springs native had written that would make it to the big screen.

“Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge” first appeared as an 11-page short story Atlantic Monthly in June 1920. Later that year, Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge was published by Doubleday, Page & Company as a small, 60 page book (with generous margins). You can read it here: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433076044944;view=1up;seq=9

To summarize the story for you, a boy named Sam lost his father to the Civil War, and that event instilled in him a grand sense of patriotism and of being part of a great nation. He followed those values like they were a religion. Upon the death of his wife, he raised his son to the same standards. His son enlisted, fought, and died in World War I. Sam, who by then was dressing up as Uncle Sam for war rallies and was referred to as such, was able to cope with the loss of his son because he knew the boy had died fighting in a war that was meant to end all wars and bring everlasting peace.

Because of his strong patriotic values, Uncle Sam supported the League of Nations, and was dismayed when the nation’s patriotism faded after the war. When the Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles for the final time, Uncle Sam took his own life to atone for the sins of the nation.

Following his death is a call to return to the noble ideals that had united the country during the war, a sense of community over self, supporting ones allies, and striving for peace. The story comes across as non-partisan and expresses disdain for party loyalties and party divisions. In an uncomplicated way, Montague highlights the patriotic spirit that Uncle Sam inspired in the people in his community, until the war was over and everyone got caught up in their own lives again, and she ended her tale with an undeniable moral message.

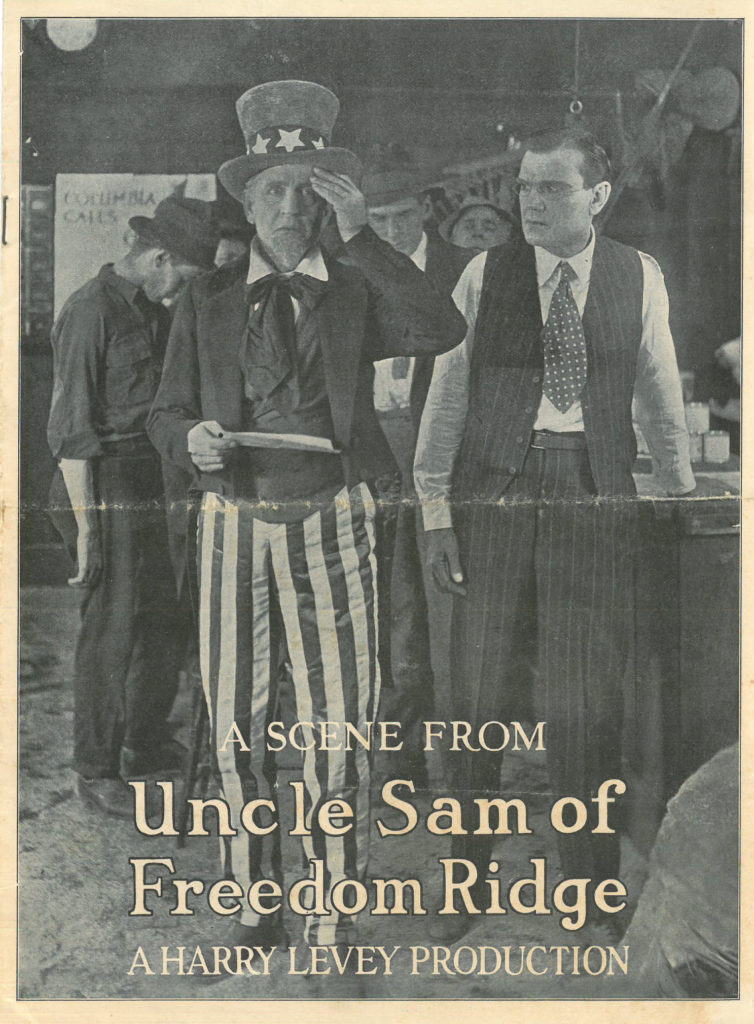

The story appears to have struck a chord with people. In the folder of correspondence we have pertaining to that work, in addition to letters from fans and a few letters from publishers seeking to know more about her, are two letters asking for the rights to make her story into a motion picture. I am not sure if either of those was the successful party, but according to IMDB, the resulting movie was released in late September of that year, 1 hour and 10 minutes of silent, black and white footage. While I cannot find any evidence that the film footage survived, at least one copy of the script exists, at the Academy Library in California.

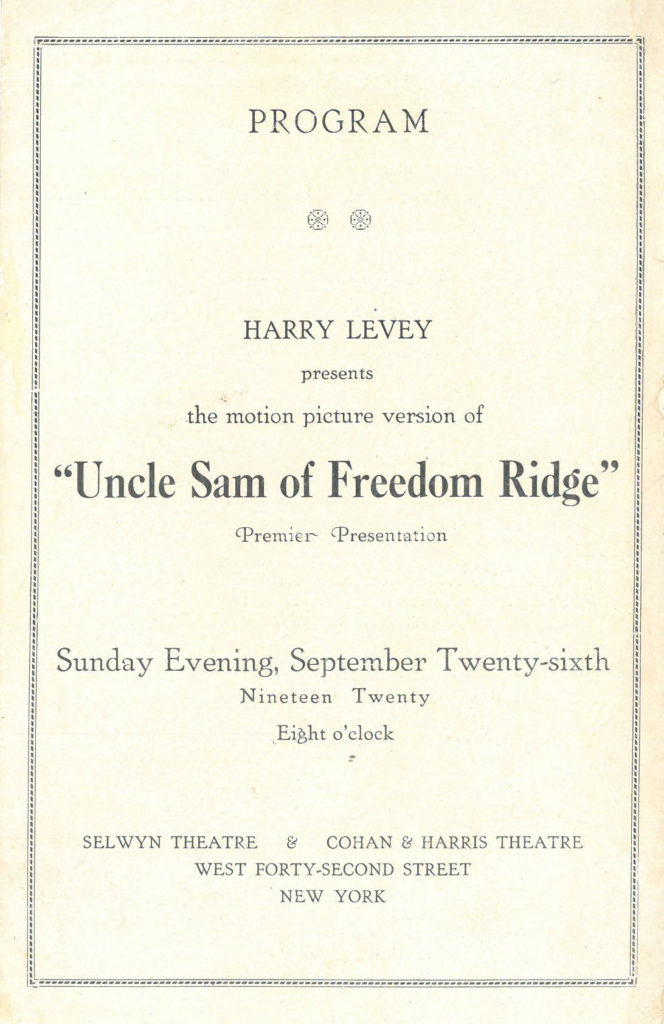

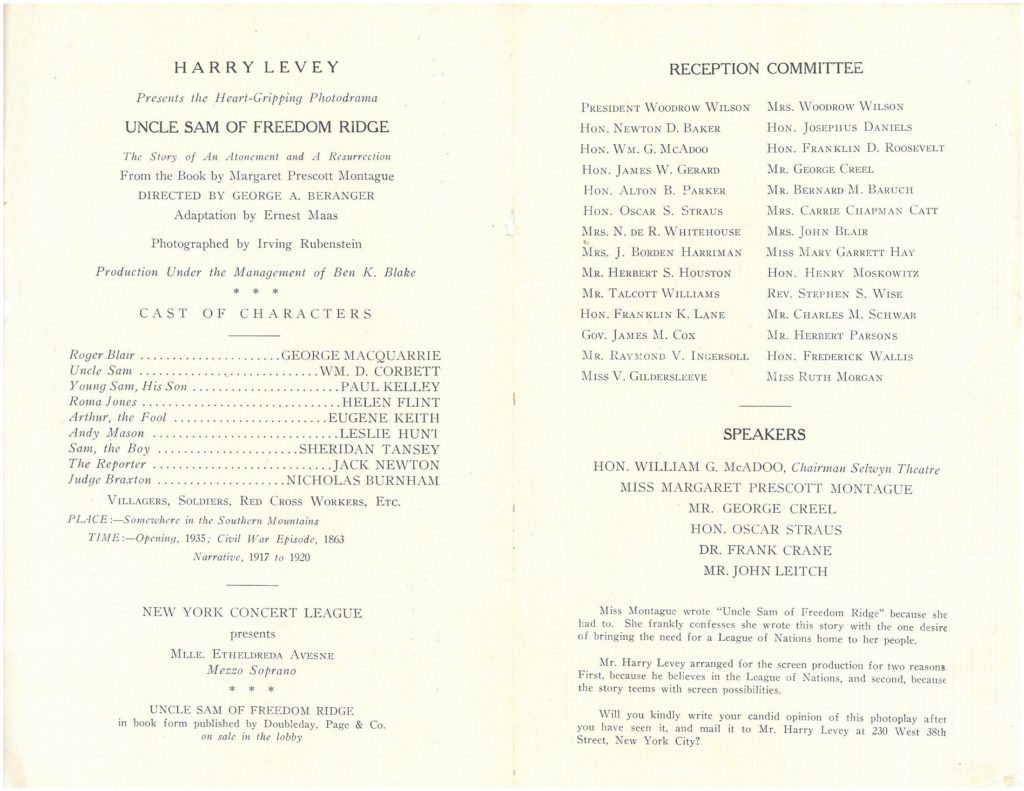

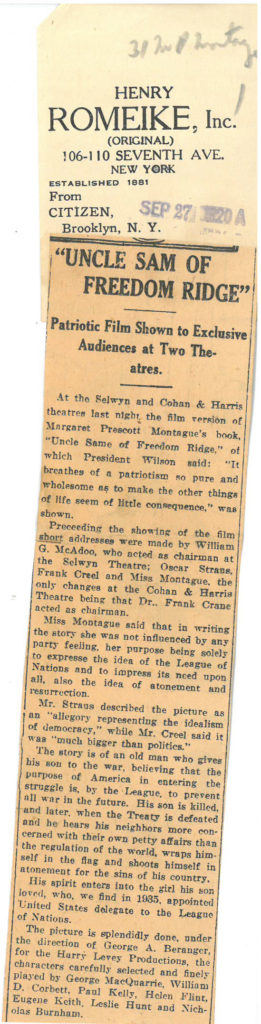

As you can see from the program above, the film enjoyed a screening on September 26, 1920, which was attended by the likes of President Woodrow Wilson, former Secretary of the Treasury Hon. William G. McAdoo, and steel magnate Charles M. Schwab, among others. According to a news clipping from the Brooklyn Citizen (Sept. 27, 1920), President Wilson said the movie “breathes a patriotism so pure and wholesome as to make the other things of life seem of little consequence.” The article also notes “Miss Montague said that in writing the story she was not influenced by any party feeling, her purpose being solely to expresse [sic] the idea of the League of Nations and to impress its need upon all, also the idea of atonement and resurrection.”

While Montague’s story clearly seems to be pro-League of Nations but non-partisan, it did become a part of the Democratic Party’s propaganda. A September 1, 1920 article from the Chicago Herald and Examiner about a Senate subcommittee on presidential campaign expenditures (titled “Chief Cox Aid Admits Shady Propaganda” and subtitled “White Planned to Distribute League Tract Disguised as Novel”) says that a congressman “intimated” that Montague’s story “has been paid for by persons who will benefit by a Democratic victory.” “Manager McMillen also had admitted that the paid-for plate [of “Uncle Sam of Freedom Ridge”] was to be published in such a fashion that the farmer and small town readers would be unable to guess that it was political propaganda or advertising.”

Another article (from the Richmond Times-Dispatch, September 5, 1920) states that the allegations from that subcommittee meeting earlier in September, especially the suggestion of English money financing this pro-League propaganda, were unproven. However, the article also notes that the early October wide release would give the film at least four weeks to try to sway people’s opinions before Election Day on November 2, 1920. It strikes me as funny that a story about patriotism, rising above political party lines, and doing the right thing on a national scale became part of a partisan ethics dispute.

Anyone interested in examining the political effects of this story through clippings, or in learning more about how it made its way from story to film (apparently, it was purchased from the author at $200 per word) are welcome to browse through the folders of clippings that Montague collected, housed here at the West Virginia & Regional History Center.

July 20th, 2019 at 1:55 pm

Very interesting research.