#ChronAmParty: Nurses

Posted by Jessica McMillen.July 6th, 2020

Blog post by Rachael Nicholas, WVRHC.

Earlier this year, May 6-12, we celebrated #NationalNursesWeek. To further that celebration, we examined the pages of historic West Virginia newspapers in Chronicling America, the historic newspaper project, #ChronAm, for nursing stories.

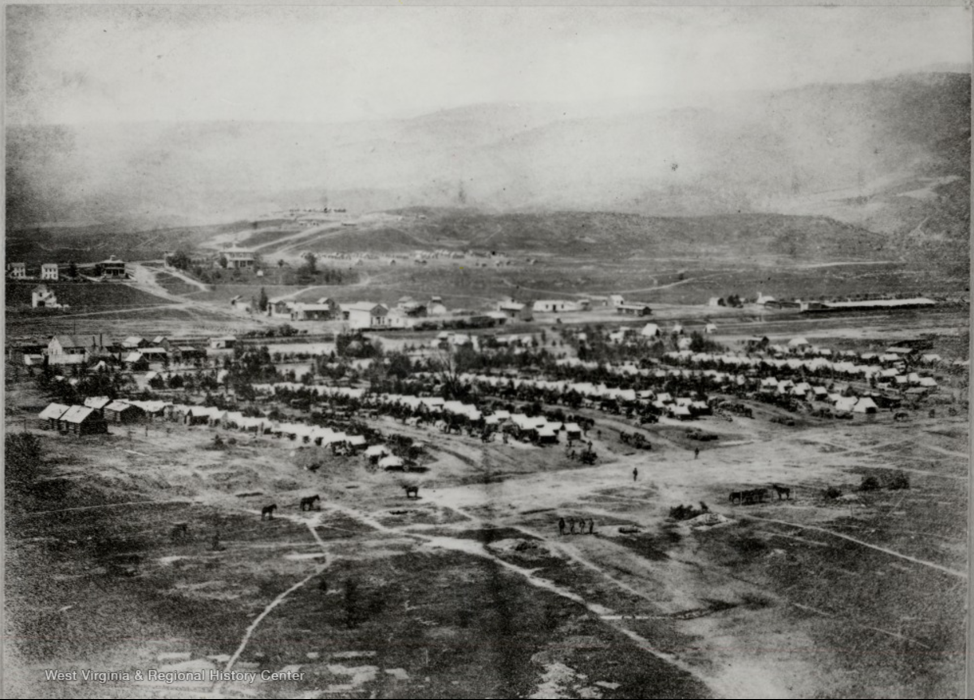

The American Civil War marked a period of significant strife for nurses. The unprecedented times facilitated the enlistment of female nurses, both Union and Confederate, to care for the sick and wounded. They oversaw diets and food distribution, managed supplies provided by the United States Sanitary and Christian Commissions, and offered emotional and spiritual care.[1] Nurses regularly encountered sick men within the ranks. Soldiers suffered from acute diarrhea, typhoid, dysentery, small pox, measles, and scarlet fever.[2] Two out of three soldiers died from disease instead of wounds. Nurses and surgeons treated 400,000 wounds in comparison to 6,000,000 cases of sickness.[3]

Nurses put themselves at risk whenever they helped an ailing soldier or civilian. They lived in a time and place that did not recognize germ theory; doctors preferred “humoral theory,” cutting into infected areas to let “tainted blood” flow out.[4] A poor understanding of germs and disease rendered nurses vulnerable but not defenseless. Nurses who recognized the link between “malarial miasmas” and sickness pursued an assiduous sanitation policy to restrict the spread of disease.[5] Cornelia Hancock, a nurse present at Gettysburg, labored tirelessly to keep her ward clean—so much so that she was accused of secreting additional supplies. “There is one woman here who has the clothes department. They call her ‘General Duncan;’ she is the terror of the whole camp,” Hancock wrote. “She came and blew me up sky high for having my ward so clean, said I must get more than my share of clothes. I answered her very politely and held my tongue. I can get along with her if anyone can.”[6] Hancock did not allow petty disputes to interfere with her diligence. The battles nurses waged against disease could become literal. After the First Battle of Winchester, a Confederate victory, Union nurses succumbed to a human enemy—not germs. One Daniel J. Martin, writing from New Creek, [West] Virginia, informed the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer that Dr. Peale, the head surgeon at Winchester’s Union hospital, “and five nurses belonging to the same establishment were made prisoners at the recent defeat of Banks.” Even “the humane old [hospital] steward Dideren was shot dead.” Martin felt melancholy at the news, which “causes many of us great inquietude,” but he continued his work. His hospital in New

Creek was expecting “three hundred sick and wounded, this day, from Petersburg.” Martin and his men had to “do their utmost endeavors to take care of them kindly and properly.”[7] The Civil War permitted little rest for those who healed the living and buried the dead.

[1] Daniel John Hoisington, introduction to Our Army Nurses: Stories from Women in the Civil War, by Mary Gardner Holland (Roseville: Edinborough Press, 1998), v.

[2] Gordon Dammann, Pictorial Encyclopedia of Civil War Medical Instruments and Equipment (Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, 1983), 44.

[3] George Worthington Adams, Doctors in Blue: The Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War (Dayton, Ohio: Press of Morningside, 1985), 194.

[4] Dammann, Pictorial Encyclopedia of Civil War Medical Instruments and Equipment, 35.

[5] Ibid., 197.

[6] Cornelia Hancock, South after Gettysburg: Letters of Cornelia Hancock, 1863-1868, ed. Henrietta Stratton Jaquette (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1937), 23-24.

[7] Daniel J. Martin, “From New Creek,” The Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, Wheeling, [West] Virginia, June 5, 1862, p. 3.