The Constitutionalist

Posted by Jessica McMillen.July 13th, 2020

By: Rachael Barbara Nicholas, WVRHC

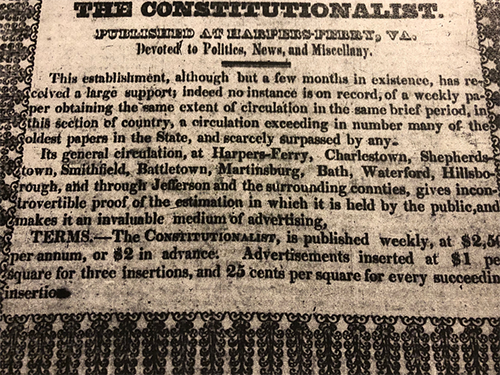

The bustling armory town of Harpers Ferry welcomed a new political paper in spring 1839. The proud editors, James R. Hayman and William S. Smith, offered a prospectus in subsequent volumes, describing their intentions: “As a political paper THE COSTITUTIONALIST will advocate the principles of the present [Democratic] Administration,” those of President Martin Van Buren, “and lend its support to carry out the various measures of political economy advanced by it.” Both Hayman and Smith revered the Constitution, “believing that ‘all powers not clearly granted to the General Government are reserved to the grantors,’” and they named their paper accordingly. As strict constructionists, they opposed any liberal interpretations or “latitudinous constructions of the Constitution as detrimental to State sovereignty.”[1] The debate between loose or strict constructions of the Constitution had shaped political discourse since the Constitution came into existence. The ghosts of Thomas Jefferson and Alexander Hamilton lingered on, with Democrats claiming Jefferson as their muse.

Opposition to Hamilton’s legacy manifested in hostility towards a national bank. The Constitutionalist regularly berated the “Bank Aristocracy” and praised Andrew Jackson, “the sage of the Hermitage,” for denouncing the Second Bank of the United States.[2] Although Jackson won the “Bank War” by vetoing its recharter bill, debates for and against a national bank did not abate. Democrats and Whigs continued to clash in their respective newspapers throughout the Jacksonian Era. The Constitutionalist’s Jacksonian politics and its hatred for national banks fueled its dedication to covering local and national elections.

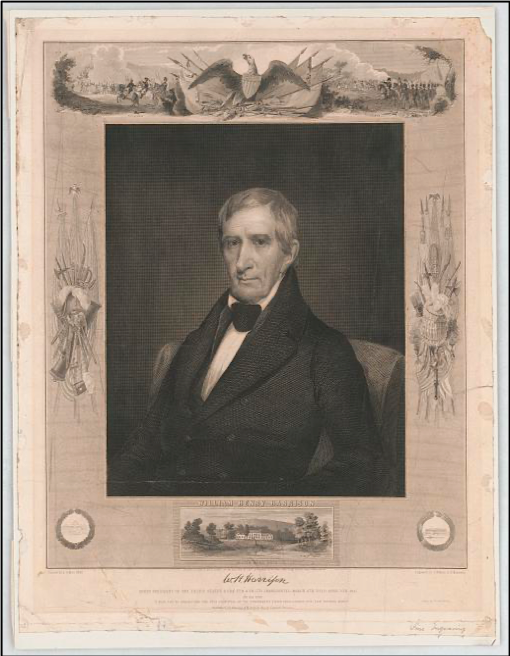

The most important election to occur during the Constitutionalist’s existence was the Election of 1840. The presidential election pitted Jacksonian darling, Martin Van Buren, against William Henry Harrison, a Whig. The Constitutionalist took an immense interest in the election, replacing the poems and light literature that traditionally occupied its front pages with political commentary.[3] It not only condemned Harrison for being a Whig, and, by association, a moneyed power in league with banking interests, but also an abolitionist sympathizer.[4] In an era of building sectionalism, the word “abolitionism” crackled across party lines, sparking heated debates. Democrats who patronized newspapers like the Constitutionalist believed it was on the rise. “The abolitionists are not dead—they only sleep,” they warned. “Their stillness is of that awful kind which announces the forthcoming of some mighty evulsion of nature.”[5] The nomination of Harrison for the Whig Party seemed to confirm their suspicions.

William Lucas, a U.S. congressman, certainly thought so. Shortly before the election, Lucas had shown “beyond the possibility of a doubt, that the [Whig] party were playing into the hands of the Abolitionists”—or so the Constitutionalist claimed.[6] Hayman had other reasons to report favorably on Lucas’s speech, which were decidedly local. Lucas’s brother, Edward, was the civilian superintendent of the Harpers Ferry armory.[7] As superintendent, Lucas dismissed competent Whig armorers and replaced them with fellow Democrats.[8] Angry employees accused him of “Loco-Foco tyranny” and establishing a partisan newspaper, the Constitutionalist, while providing its editors with free public housing.[9] Whether he funded it or not, the Constitutionalist definitely favored Lucas’s interests. Hayman and Smith printed toasts in his name, supported his brother, and censured his opponents.[10]

On one memorable occasion, they reprinted an address from Richard Barton, dated October 16, 1830, in which Barton denounced the “JACKSON MEN” who were “directly or indirectly concerned in the INFAMOUS attempt to SULLY MY HONOR” when he ran for state senator. Hayman and Smith responded tersely: “Comment on the above is useless; it will go to the reflections of all [intelligible] and democracy will stand appalled at the idea of supporting a man who could utter such sentiments.”[11] The editors added that Barton had been campaigning against Hierome L. Opie, but they failed to mention the Democratic candidate for the House of Delegates: Edward Lucas.[12] It was not a coincidence that Hayman and Smith used Barton’s speech against Edward’s party to support William’s bid for the House of Representatives in 1839. Local readers would have implicitly understood the connection between Barton and the two Lucases.

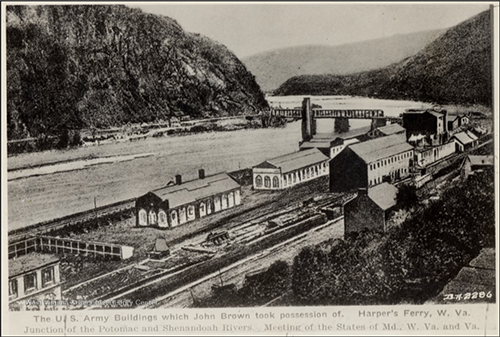

They probably understood why Hayman shuttered the Constitutionalist, as well. The newspaper lasted two years before its closure in 1841. The presidential victory of William Henry Harrison had facilitated Lucas’s removal from the armory as superintendent, and Henry K. Craig, a military superintendent, took his place in April 1841.[13] Hayman put his Shenandoah Street home and the newspaper press up for sale in March and May, just as Lucas was preparing to leave.[14] Without Lucas’s patronage, Hayman must have recognized the tides of political change. This may have cemented his decision to leave Harpers Ferry, especially in the absence of William Smith, who had ceased to be a contributing editor between June 12 and September 11, 1839.[15] With Hayman’s departure, the Constitutionalist finished its brief but influential run.

[1] James R. Hayman and William S. Smith, “Prospectus of the Constitutionalist,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, May 1, 1839.

[2] “Truth is Mighty and Will Prevail,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, May 23, 1839.

[3] Compare Volume I, no. XXXVIII (January 8, 1840) to Volume I, no. II (May 1, 1839).

[4] “Harrison and Abolitionism: The Maine Election,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, September 24, 1840.

[5] “Abolitionism,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, June 12, 1839.

[6] “Shepherdstown Address,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, September 24, 1840.

[7] Merritt Roe Smith, Harpers Ferry Armory and the New Technology: The Challenge of Change (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1977), 262.

[8] Ibid., 261.

[9] Ibid., 262.

[10] “Democratic Dinner,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, June 5, 1839.

[11] “Virginia Elections,” The Richmond Enquirer, Richmond, Virginia, October 26, 1830.

[12] “Democrats Read,” The Constitutionalist, Harpers Ferry, Virginia, May 23, 1839.

[13] Smith, Harpers Ferry Armory and the New Technology, 268.

[14] Jill Y. Halchin, ed., Archaeological Views of the Upper Wager Block, a Domestic and Commercial Neighborhood in Harpers Ferry (Washington, DC: National Park Service, 1994), 2.10.

[15] Smith’s name had been dropped from the acknowledgments in the intervening months.

October 7th, 2023 at 10:44 am

Mr. James R. Hayman is related to me through the marriage of his daughter, Hannah Hayman, to Armistead Mason Ball. Do you know what happen to James Hayman AFTER he left Harpers Ferry in 1841???

Thank you. Pete