Farmers’ Repository and Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository

Posted by Jessica McMillen.July 20th, 2020

By: Rachael Barbara Nicholas, WVRHC

A flourishing newsprint culture bloomed in the streets of Charles Town, West Virginia, before the Civil War. The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository (VFP&FR), one of several antebellum newspapers, devoted itself to a series of political topics, including slavery, congressional representation, and internal improvements. Richard Williams and William Brown edited its predecessor, the Farmers’ Repository, from April 1, 1808, to February 28, 1827, before merging it with the Virginia Free Press in March. The new editors, John S. Gallaher and J. T. Daugherty, opposed the incumbent president, Democrat Andrew Jackson, and promoted the National Republican Party.

Gallaher was professionally and politically qualified to oversee the newspaper. He had previously edited the Virginia Free Press and the Ladies’ Garland, an early example of a women’s magazine. Gallaher assumed full control of the paper after Daugherty “disposed of his interest” on October 6, 1830.[1] Just two weeks later, Gallaher won a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates with Edward Lucas, a future superintendent of the Harpers Ferry arsenal. The paper quietly mentioned Gallaher’s political victory, noting the number of votes awarded without highlighting his role as editor. [2] Astute readers understood the connection, and they accepted the paper as Gallaher’s official mouthpiece. Within its pages, Gallaher shared his opinions on presidential candidates and internal improvements, advocating for the expansion of the railroad through Charles Town. The routing of railroads through the Eastern Panhandle would influence the county’s subsequent inclusion in West Virginia.

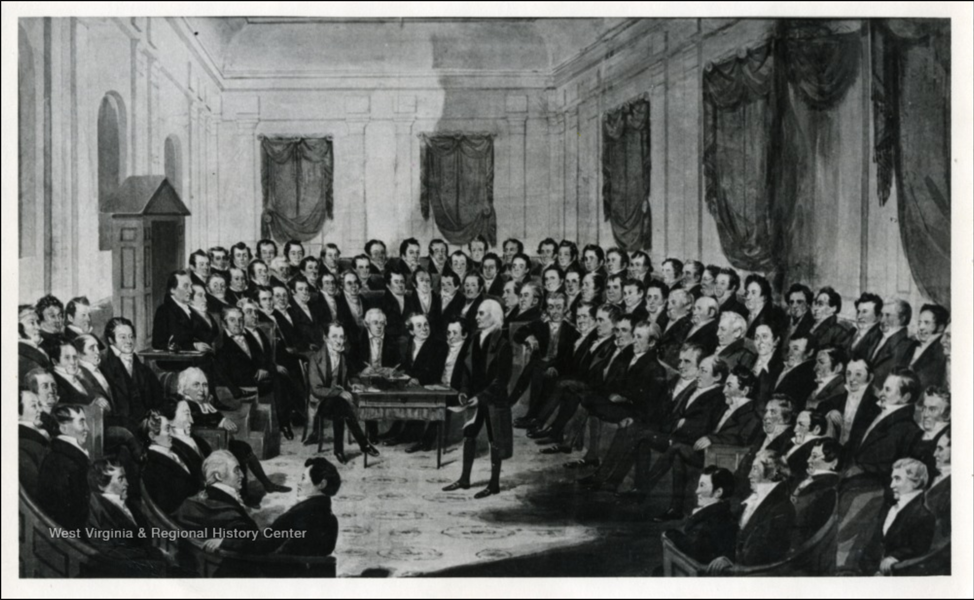

Another issue that facilitated divisions between eastern and western Virginia was congressional representation. The paper was at its peak in 1830 when Virginia was revising its state constitution. Two concerns dominated the proceedings of the Constitutional Convention: representation and suffrage. Western delegates petitioned for apportionment in the General Assembly on a white basis; they opposed a system of “federal numbers” that included slaves as three-fifths a person, thereby granting additional representation to the eastern slaveholding counties. A “common man” writing for the VFP&FR deemed the system unjust. It is “the wish of the majority for representation to be uniform, according to the white population of the whole State, and not with regard to wealth,” he wrote. “In other words, not for slaves, who, as property, can be considered no more than so many cattle to give a man, where slaves are possessed, greater preponderance in the scale of politics, than one where there is little or no slavery.”[3]

Although that was true for western delegates, the rest disagreed. Apportionment according to the total white population failed by two votes, as did universal white male suffrage.[4] Two western delegates, John R. Cooke and Richard H. Henderson, received backlash for voting against western interests. As late as 1910, historian Charles Ambler accused Cooke and Henderson of “disloyalty, approaching treason” for supporting the Gordon compromise, which gave the east a 24-person majority in the House of Delegates.[5] Cooke countered similar claims in a series of letters reprinted in the VFP&FR. He argued “that Gen. Gordon’s plan, adopted on the 19th of December… was the successful rival of the plan of white population and federal numbers, instead of being the plan itself,” adding that he “supported the plan of representation now submitted to you, because I thought it the nearest approximation to the ‘white basis’” in a second letter.[6] Gallaher and Daugherty did not challenge Cooke’s assertions, indicating some level of agreement. They thought the new constitution was better than its predecessor, even though it did not “give the West all which we were justly entitled.”[7]

The integral nature of slavery to political representation may have influenced Gallaher’s stance on another critical issue: colonization. Americans like Gallaher who promoted colonization believed the settlement of slaves in Africa could eliminate the problems associated with American slavery, including political representation. It was not uncommon for writers to denounce the violence of slaveholders or even slavery itself in the VFP&FR. One correspondent did not mince words when he said the “Eastern gentlemen… should hail with pleasure the arrival of the period when Virginia should get rid of the evil of slavery.”[8] Such powerful words, recalling Jefferson’s own objections to slavery, did not suggest any real love for racial equality. Advocates of colonization were keenly interested in the removal of slaves and free African Americans. Hoping for a whiter society, Gallaher offered his solution: “Let the State provide ways and means for transportation to Liberia, of all negroes who were entitled to freedom previous to 1806… And let it be made the duty, by law, of all persons who hereafter emancipate slaves, to provide the means of their removal from the commonwealth.”[9] Gallaher’s advice complied with the 1806 law that mandated the emigration of freepersons within a year of their manumission. Although seemingly calculated to assist African Americans, his declaration betrayed a greater desire to help white Virginians than emancipated slaves. Gallaher and likeminded men hoped their fellow citizens would support the American Colonization Society after Nat Turner’s rebellion in Southampton, a topic that received much attention in the VFR&FR.[10] The slaughter of slaveholding families probably bolstered Gallaher’s belief that slavery was a threat to white Americans that could only be alleviated through colonization.

Gallaher continued to promote colonization in the pages of the VFR&FR until May 1832, when he announced impending changes for the paper. “We desire, about the first of October next, to make an addition to our form, and some general improvement in the appearance of the paper,” Gallaher wrote. “This improvement is contemplated, in order to keep pace with the increasing patronage extended to the FREE PRESS, and to give it a character worthy of competition with any weekly paper in Virginia.”[11] He was wrong in but one respect. Within two months, the Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository had become the Virginia Free Press, beginning a new chapter in Gallaher’s publishing history.[12]

[1] J. T. Daugherty, “The Free Press,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, October 6, 1830, p. 3.

[2] John S. Gallaher, “Jefferson Election,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, October 20, 1830, p. 3.

[3] A Common Man, “For the Virginia Free Press,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, February, 3, 1830, p. 1.

[4] Ronald L. Heinemann, Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607-2007 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 173-174.

[5] Charles Henry Ambler, Sectionalism in Virginia from 1776 to 1861 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1910), 166, 163.

[6] John R. Cooke, “The New Constitution,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, February, 3, 1830, p. 2; John R. Cooke, “The New Constitution,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, February, 10, 1830, p. 2.

[7] J. T. Daugherty and John S. Gallaher, “The Free Press,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, February 17, 1830, p. 3.

[8] Correspondent, “The Legislature,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, December 22, 1831, p. 2.

[9 ] John S. Gallaher, “The Free Press,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, October 27, 1831, p. 3.

[10] Unknown author, “Colonization Society,” reprinted in The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, September 22, 1831, p. 1.

[11] John S. Gallaher, “Virginia Free Press,” The Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, Charles Town, West Virginia, May 3, 1832, p. 1.

[12] John S. Gallaher, The Virginia Free Press, Charles Town, West Virginia, July 19, 1832, p. 1.