To There and Back Again: The Many Moves of John Brown’s Fort

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.October 19th, 2020

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Associate Curator for WV Books & Printed Resources & Rare Book Librarian

October 16, 2020, was the 161st anniversary of John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. Over 160 years after the event, John Brown, and the people and events surrounding him, remain a powerful topic for depiction such as the new program currently airing on Showtime, “The Good Lord Bird” starring Ethan Hawke as John Brown.

The last couple of years have seen several books published on figures that were involved in the raid including the story of an escaped enslaved person, The Untold Story of Shields Green by Louis A. Decaro, Jr., Five for Freedom: The African American Soldiers in John Brown’s Army by Eugene L. Meyer, The Zealot and the Emancipator: John Brown, Abraham Lincoln, and the Struggle for American Freedom by H.W. Brands, and of course, the book that inspired the Showtime series, James McBride’s novel, The Good Lord Bird.

While Brown remains the subject of much interpretation, little has been said about the multiple moves of the Harpers Ferry building Brown and his men occupied on that fateful raid, the Arsenal Engine House, later to called John Brown’s Fort.

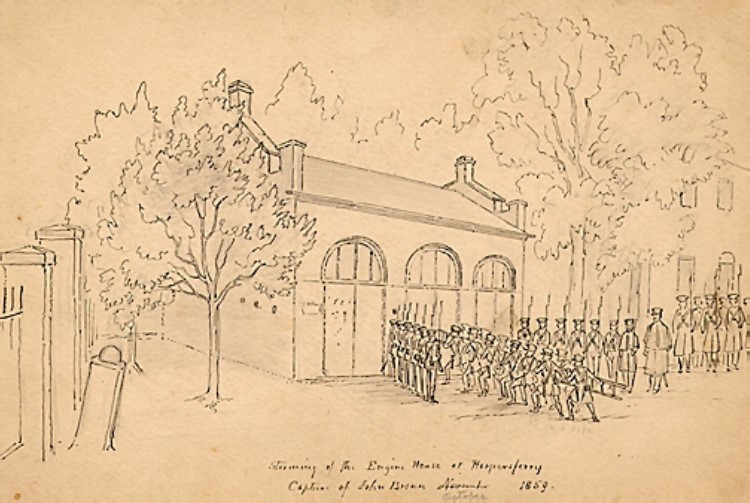

At the time, the engine house served as the government arsenal where guns and ammunition were stored. Brown’s plan was to capture the armory and the engine house, using the ammunition inside to supply a hoped for uprising of enslaved people he believed would join him to fight for freedom following his initial strike. This did not happen. Brown and his small band of men were left to fend for themselves. The following day, U.S. Marines arrived to storm the engine house, led by Col. Robert E. Lee and his aide, J.E.B. Stuart. Brown and his surviving men were captured, tried and executed.

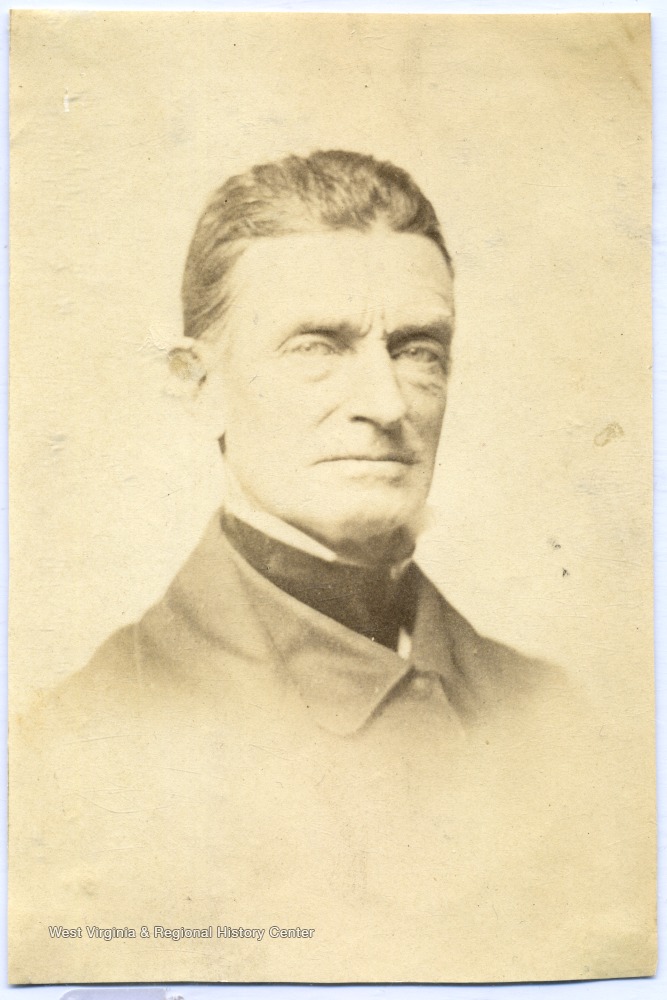

This drawing was made on the scene by David Hunter Strother, a journalist, artist and illustrator, from Martinsburg. Strother, pictured below, who used the pen name, Porte Crayon, often wrote articles and provided illustrations that frequently appeared in the pages of Harper’s Monthly magazine.

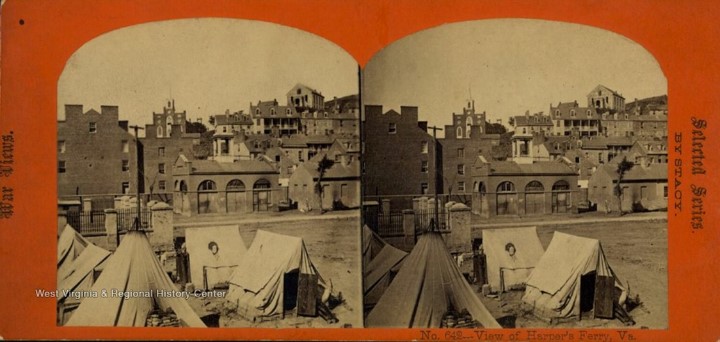

During the Civil War, the engine house was the only part of the armory to survive. This stereograph card shows the tents of Union troops stationed in front.

By 1885, still in its original location in downtown Harpers Ferry, the engine house was used as a tourist attraction. The words “John Brown’s Fort”, seen here, were painted over the arches where windows were formerly.

First Move:

In 1891, the engine house was purchased by a group, headed by Iowan, A. J. Holmes, a former confederate soldier and congressman, with plans to make it an exhibition at the upcoming World’s Columbian Exposition, to be held in Chicago in 1893. The fair was planned as a celebration of the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in America.

This was to be the first move for John Brown’s fort. Since Chicago is a long way from Harpers Ferry, the engine house was dismantled and shipped via railroad. Once it arrived in Chicago, it was reconstructed inside one of the fair buildings. Unfortunately, it drew little attention. Reports state that only 11 people came to view John Brown’s Fort in 10 days.

Second Move:

Unhappy with the turnout, the second move for the building occurred when the fort was dismantled once again and moved to an empty lot where it was abandoned.

The following year, a Washington D.C. journalist, Kate Field, publisher of Kate Field’s Washington, a weekly magazine, began a fund-raising effort to save John Brown’s Fort and move it back to Harpers Ferry.

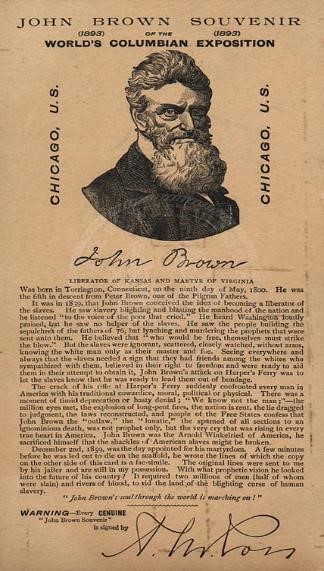

Although, no photographs could be found documenting John Brown’s Fort as an exhibition at the Columbian World’s Fair, or dismantled and abandoned on the vacant lot, the newspaper, the Wheeling Intelligencer, reported on June 21, 1893, an article entitled “OUR STATE BUILDING,” referring to the West Virginia building constructed on fair grounds. Each state was responsible for building a site to exhibit their state’s products and industries. The article touted the 30th anniversary of the state and reported memorabilia on display, “There are a number of interesting relics to be found in the building, among which are the chair and safe used by Lee in writing his terms of surrender to Grant, and several John Brown relics.” Fair goers visiting the West Virginia building could have picked up this John Brown Souvenir ticket, pictured below.

Third Move:

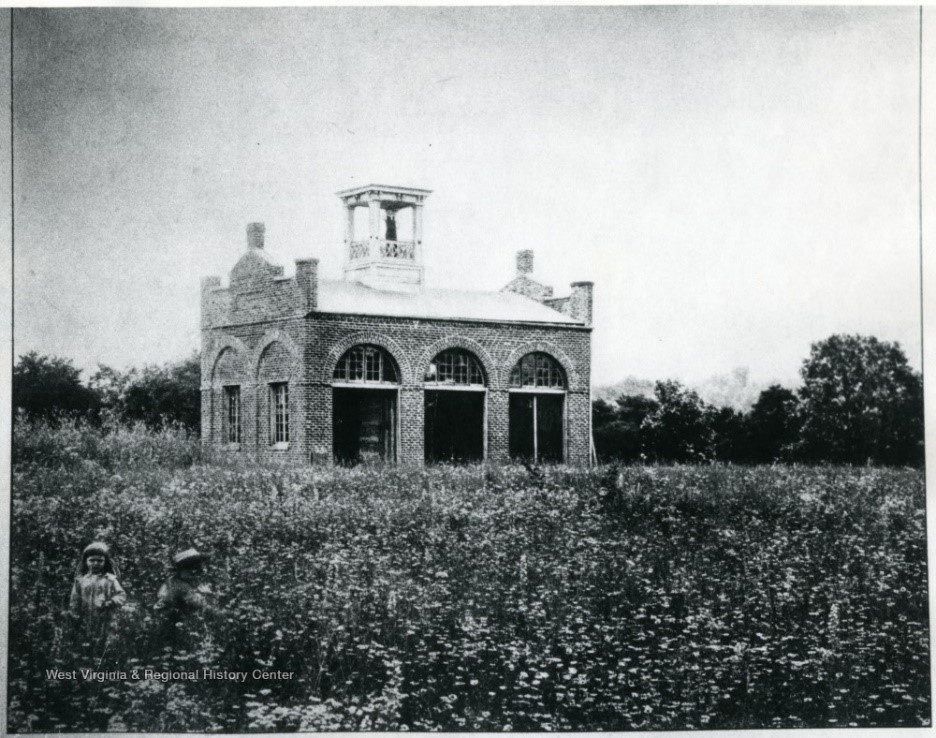

Things began to look up for John Brown’s Fort when a local farmer, Alexander Murphy, encouraged by Kate Fields fundraising efforts, donated five acres of his property for the site. The Baltimore and Ohio railroad stepped in and agreed to ship the building at no charge. In move number three, a mere two years after it was shipped to Chicago, John Brown’s Fort was successfully returned to Harpers Ferry, and reconstructed on the Murphy Farm.

Photograph approximately 1900

Although it remained on the Murphy Farm for a number of years, the building had no purpose. Positioned out of town, it failed to serve as a tourist destination. Things took a turn for the worse when it was used as just another farm building to store fertilizer.

Move Four:

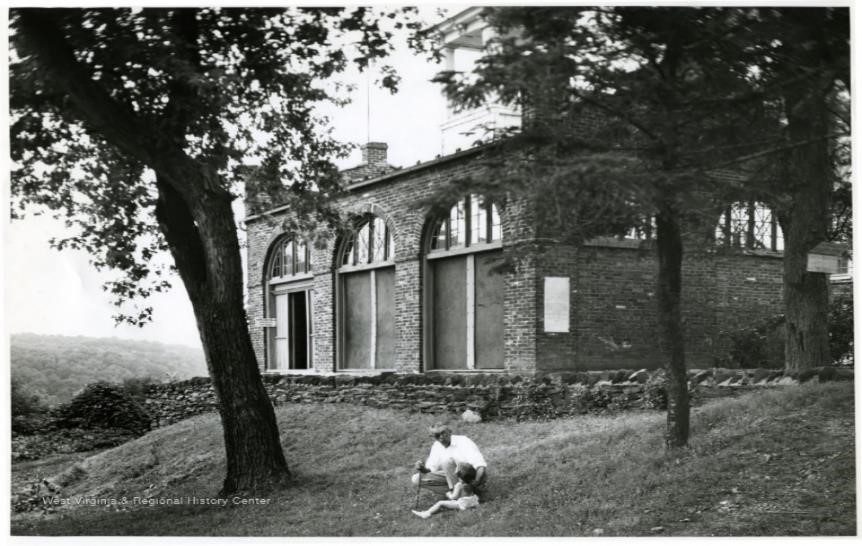

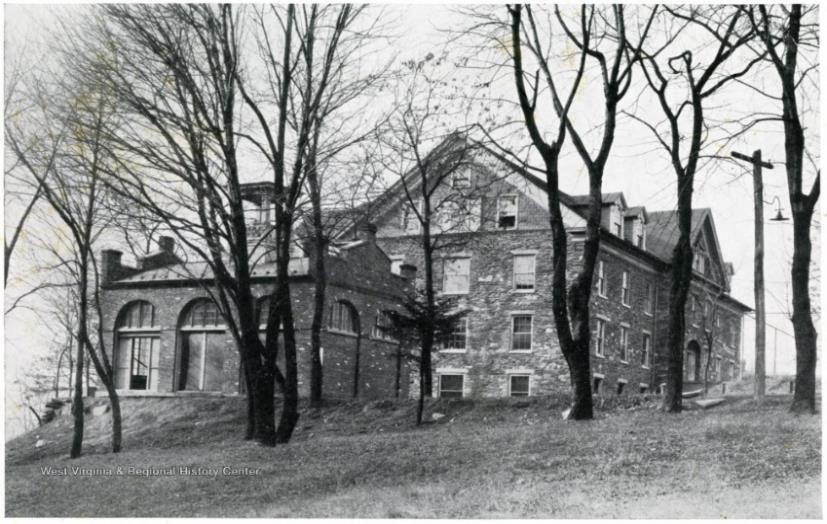

1909 was to be an important year for yet another rescue and rehabilitation of John Brown’s Fort. That year was the fiftieth anniversary of John Brown’s raid. In move number four, the building was once again removed, reconstructed and renovated, this time on the campus of Storer College, also located in Harpers Ferry. Storer College, with its roots in the Civil War, had a strong connection to the fort. Founded by Freewill Baptists immediately following the Civil War, and dedicated to the education of African Americans, Storer College was housed in Harpers Ferry buildings that served military purposes during the war.

John Brown’s Fort was to remain on the campus of Storer College, serving as museum housing John Brown and Harpers Ferry memorabilia. Though Storer College closed its doors as an educational institution following the passage of the landmark case, Brown vs Board of Education, in 1954, John Brown’s Fort remained on its campus. But not for long.

Move Five:

In its fifth and final move, John Brown’s Fort was once again purchased and relocated, this time by the National Park Service, who became the owners of the Storer College campus in 1960.

Harpers Ferry NHP Historic Photo Collection, Catalog #NHF-3155

While positioning the fort on the original site would have been ideal, it was impossible due to a railroad embankment constructed on that site 1894, when John Brown’s Fort was sitting lonely and abandoned in a field outside Chicago. The Park Service re-sited it as close to the original site as possible, a mere 150 feet away from its first home.

And that is where John Brown’s Fort remains today, restored and open to visitors as an important historical site in one of the most important moments in West Virginia history.

All of the books mentioned in this post and many of the photographs are available at the West Virginia and Regional History Center, open by appointment to West Virginia University affiliates only during the pandemic.

Resources:

- All images from the West Virginia and Regional History Center photographic collection, West Virginia History OnView, with the exception of the Fort during transfer and the final image of the Fort today.

- John Brown’s Fort by Clarence S. Gee. West Virginia History, Volume 19, Number 2 (January 1958), pp. 93-100. http://www.wvculture.org/history/journal_wvh/wvh19-1.html

- Wheeling Intelligencer quote: http://www.wvculture.org/history/miscellaneous/columbian02.html

- John Brown’s Fort exhibition ticket, World’s Columbian Exposition. West Virginia Archives and History, “On This Day in West Virginia History:” http://www.wvculture.org/history/thisdayinwvhistory/0314.html

- Images and information from the National Park Service: https://www.nps.gov/hafe/learn/historyculture/john-brown-fort.htm

- John Brown’s Fort in Chicago, 1893: https://watermark.silverchair.com/987906.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAqUwggKhBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggKSMIICjgIBADCCAocGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQM2GkbJ8GD9AWvV6bdAgEQgIICWE5QHsa_ERnFRSvhtTG0adoKcH3d1vcW9GN9fHU1w0xarzP-7CbXCOUAjjD29KIHZTDwR_cKz0pBkfNEN4kh7fu3S9yzsehwtX0Xod8GBCC-hVyFcsYuMgMBi-uFSRgH22xCs3NhGDCkSRTIaGPFjx9rR6yDi8o1sJGIVF6G8IgZ0Y4GWmByiXKiQ7zXVGj9zJK7lr-UgwvvwzG73EeN8svVL0k-pnBgnRhHXQdT3bJqwp-CQ6QkM30fG4QR07nl-MpdeIZqmDyglbWbeCtyeQAO7j86bpWCYr-vkVgHOAZAcsDbbzapMIX4tmRnJF3Mh-0uBSocZwOiw4FZDlw-7IMj2WnmgSBa4ONE34L55Y_IbzQTf5J-KjGkCx8qPktZ_cZEQhp_fvAq4MEi0k20R6xABPxJue0kbjYx8CUvB7CnI3HWeLy0xco6LRAsITRY2sbd8-A40cS2HnDRkOWLkfwS-MJrLw2M_9jxx-QuNuh9Yqn1_fWv_Uoq329tGtJI-kaHAQAdn_1uPo3cLw7K9LMGHrLgEZSLYYr3-8WkHHyP4vM2Fx8Xe3FWDbJbOFD6o_jxbeLum3NLLEQJzrziVxNYt884Mw7SMOY2rRS4yO_Zi505VzR6VAjI4c8rzYCcN6TPLdoyrLFOX9eg_A9bcjG_Q98idRLtMgHjnHZiUvvcosioHIpsE–RefhS9_l0SRiCEwFq2BWzE6yEFDD5gb7_neNr_lV-3bxrs1uIDCPTahdVYHT2s8QqiNBl3FIvU3d25gDI2PDatbsUgL2J5jq00DMe_OXHqw

- Wikipedia: John Brown’s Fort: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown%27s_Fort

- Wikipedia: David Hunter Strother: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Hunter_Strother

November 24th, 2023 at 6:37 pm

The current reconstruction of John Brown’s Fort (with guard house on the left and fire engine bays on the right) is a mirror image of the building seen photographed in its original location and later at Murphy Farm. Why is this so?