The Rumors of His Death were Exaggerated: The Darlington-Hutton Shooting Revisited

Posted by Mary Alvarez.May 1st, 2023

Written by Luke Masa, Doctoral candidate, History & WV Newspaper Project Grant Assistant

In a previous post, I wrote about an early twentieth-century West Virginian newspaper editor, Charles Peyton Darlington (also known as “C.P. Darlin[g]ton”, with or without the “g”), shooting and killing a man in an argument over politics. As it turns out, that man, Woodford (not “Woodward”) Hutton, did not, in fact, perish by Darlington’s bullet. Hutton actually lived another 26 years following the incident. And moreover, Darlington, already 40 years old at the time of the shooting, lived to be 98! Below is a brief attempt at correcting the record and outlining historical methods through biographies of both men.

I realized my mistake while further investigating Darlington’s life after coming across his name once more during the course of my newspaper research. Perhaps it should not have surprised me to encounter him again, since like many West Virginia newspaper editors of his day, Darlington moved around quite a bit, and worked on a lot of papers. For example, before coming to Randolph County, where he shot Hutton, Darlington edited the newspaper that I am currently researching: the Webster Echo out of Webster Springs, Webster County.

In confirming that the editor of the Echo circa 1896 was indeed the same man who would go on to do a brief turn at the Randolph Enterprise and, while there, violently attempt to silence an interlocutor, I used a combination of census records, keyword searches, and obituaries. These sources returned evidence of Darlington’s decades-spanning career in the newspaper business – something I found very odd for an alleged killer to have had. But I could not uncover references to jail time or even a trial with respect to Darlington.

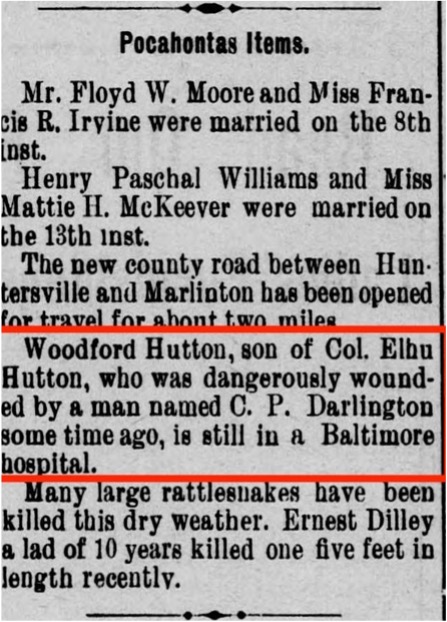

That prompted me to look into Hutton. But it turned out that I had his first name incorrect. That meant that I could not initially find records of him, whether in other papers or elsewhere. So, I looked instead for his father, Colonel Elihu Hutton, who was also referenced in reports of the shooting. Elihu Hutton’s 1900 census record listed members of his household, including a 24-year old son named Woodford. Searching “Woodford Hutton” rather than “Woodward Hutton” in Chronicling America’s online database returned several hits, some dated after 1900. One from 1910, a reprint of a story out of the Grafton Republican in the Fairmont West Virginian, placed Woodford and his father in Grafton that April. What’s more, the 1920 federal census lists Woodford Hutton as a resident of Huttonsville at the time. Thus the Clarksburg Telegram’s report of July 13, 1900 must have been wrong, while Staunton, Virginia’s Spectator and Vindicator got the story (and name) right: as of August 24th of that year, Woodford Hutton, while “dangerously injured” was nevertheless still alive in a Baltimore hospital.

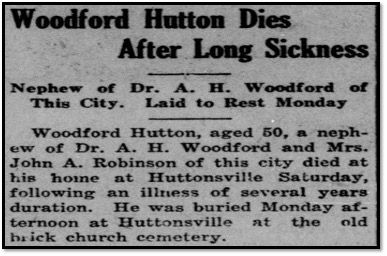

Yet even though Hutton did not die that day in July, his life at that point was unfortunately already nearly halfway over. Hutton’s actual passing occurred in early December 1926, with the Belington Progressive publishing his obituary. Noting that he had just turned 50 after having suffered a long illness, the Progressive reprinted a story from Elkins’ Intermountain which celebrated Hutton’s accomplishments in farming as a cattle rancher, explaining that he had been head of a local Cattlemen’s Association.

And meanwhile, despite being 16 years Hutton’s senior, Darlington ended up outliving the man he nearly killed. Darlington, a native of Weston, seat of Lewis County, started and finished his career in the press there. Upon Darlington’s death in 1958, both the Weston Democrat and its counterpart the Independent published obituaries for him. According to the Democrat, Darlington got his start at that very paper at the age of 16, only nine years after its founding. Darlington himself, in turn, founded the Independent in 1894. He would end up working at, in addition to papers already mentioned, the Logan Banner, Buckhannon Delta, and the Buckhannon Record, among others. The Democrat (but not the Independent) noted Darlington’s time at the Enterprise, which it wrote was only “for a year”, without elaborating any further. Coming back to Weston and the Democrat by 1913, Darlington retired during the First World War, eventually living at Jackson’s Mill with his wife. That he lived nearby the boyhood home of Stonewall Jackson was not his sole connection to the Civil War, however. As a child in 1863 he was among the inhabitants of Weston who were sent to Camp Chase in Columbus, Ohio as Union prisoners upon the recapture of the town from Confederate forces.

In the end, I’m glad I caught my error and am pleased to have the opportunity to fix it. Ideally in disciplines like History this process should be a common occurrence, through mechanisms like peer review, though only so much can be caught. Furthermore, historians are not stenographers of the past so much as we are interpreters. Hence, we continuously revise and rewrite, changing not the facts but what we make of them, or in cases like this, discovering new facts which force us to update our knowledge of a given situation. We understand that our sources are fallible and can even be contradictory. This requires us to leave room for the possibility that we may be proven wrong in the future. Therefore I hope this rough sketch of Darlington and Hutton’s lives beyond their brief and nearly fatal meeting serves to better contextualize both West Virginia’s history and how history writing is done.