Letters from ‘Yours, Bob’; an Untold Story of Heroism and the Cost of the Second World War

Posted by Mary Alvarez.January 17th, 2024

Written by Hannah Johnson

When considering the impact of the Second World War, it is easy to focus on statistics and figures on a global scale. Over 60 million lives – civilian and military – were lost between the summers of 1939 and 1945. The United States alone, despite entering the war in 1941, suffered an estimated 418,500 losses.2 These figures can be described in a number of ways; staggering, overwhelming, perhaps even awe inspiring when one considers humanity’s capability for self-destruction. But they are also dehumanizing. In considering war on a global scale, the story of the individual is lost; and thus, their legacy as well.

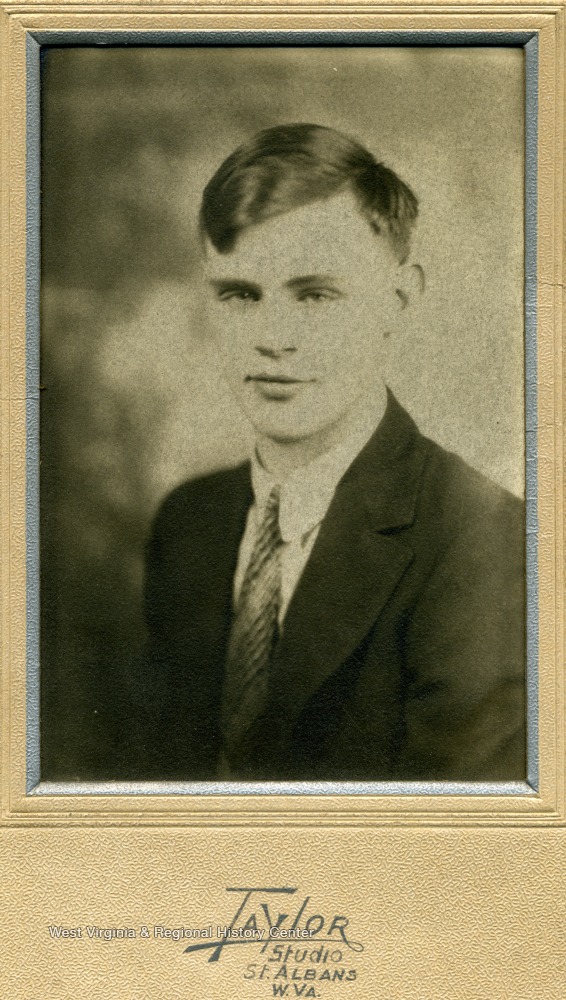

Robert ‘Bob’ Scott was twenty-two years old when he, along with the rest of his company, were ordered to take Busham, Germany, on February 27th, 1945.3 By nightfall the next day, February 28th, Scott would be dead. Through primary sources gathered and stored in the West Virginia and Regional History Center, the details of his heroic actions that day are preserved. But most students who attend WVU, the university Scott graduated from and went on to teach at, will never know of Robert Scott. Those who do recognize the name likely remember seeing it engraved on a plaque outside Oglebay Hall alongside dozens of others as they rushed to their next class. But Scott’s story is one of value, a testament to not only those who lost their lives in the Second World War, but also the impact of a single, devoted individual in a world that’s seemingly tearing itself apart. This blog will attempt to encapsulate the story of Robert Scott, his sacrifice, and the legacy he left behind for his peers to embody.

Born in 1922, Robert F. Scott Jr. was raised in post World War I America. Originally from Pennsylvania, he eventually ended up in Kanawha county, West Virginia.4 While little is known about his upbringing, it can be surmised from his own writings and those of his parents that he came from a loving family, and one that supported his later academic endeavors. Scott attended West Virginia University, graduating with the class of 1942 and obtaining his undergraduate degree.5 An important facet of his time at WVU, and one that would later immortalize his story, was his relationship with Dr. J Clark Easton. Mrs. Scott, Robert Scott’s mother, wrote to Dr. Easton after Scott’s death stating, “[Robert] worshiped you, Dr. Easton. You were a part of our family. It was Dr. Easton this and Dr. Easton that.”6 This excerpt, among others, indicates a clear admiration on the part of Scott in regards to his professor and later colleague.

Throughout his time at WVU, Robert Scott not only obtained his degree, but also left a lasting impact within the History Department, particularly through his relationship with Dr. Easton. As most of the letters found in the WVRHC archives were correspondence between Dr. Easton and Scott, it is valuable to understand their relationship. After receiving news of Scott’s death, Dr. Easton wrote to Mr. and Mrs. Scott regarding their son and his passing. In this letter, Dr. Easton describes Scott not only as a pupil and peer, but as a dear friend. In regards to his academic endeavors, Dr. Easton notes, “Bob took every course I offered and was far and away my best student… his enthusiasm, industry, and intellectual grasp of historical subjects I have rarely seen equalled.”7 As this excerpt eloquently relates, Scott was an engaged, driven student that stood out among his peers.

When considering the loss of such a bright, promising individual, Dr. Easton goes on to write, “I cannot let this sad occasion pass without expressing to you my profound sympathy in your loss. We here in the History Department feel that we in part share this loss with you.”8 The loss of any young person is indeed a tragedy, but Dr. Easton’s words indicate a deeper sense of collective grief felt within the History Department and thus the University itself. Scott leaving such an impact, especially as someone as young and new to academia, indicates a connection to Dr. Easton and the University that went beyond a transcript and a diploma. It is important to keep this relationship in mind as the letters Dr. Easton and Scott exchanged are examined to not only piece together his story but also to retain a sense of the person that Scott was.

Another important aspect of Scott’s time at WVU, both as a student and a teaching assistant, was WVU’s involvement in the war effort as well as Scotts own decision to enlist. In broader context, West Virginia was a state that more than contributed to the overall war effort. As Belmont Keenly describes in “Soldiers and Stereotypes: Mountaineers, Cultural Identity, and World War II”, West Virginia “[ranked] fourteenth among the forty-eight states in terms of proportion of population who served. These figures put West Virginia in the top one-third of states as a percentage of the population who joined the Army. While many of these young men were drafted, many more chose to enlist.”9 West Virginia and her citizens were invested in the war effort, and this dedication logically bled over into higher education, considering that college age men were in the prime demographic to be drafted or to enlist.

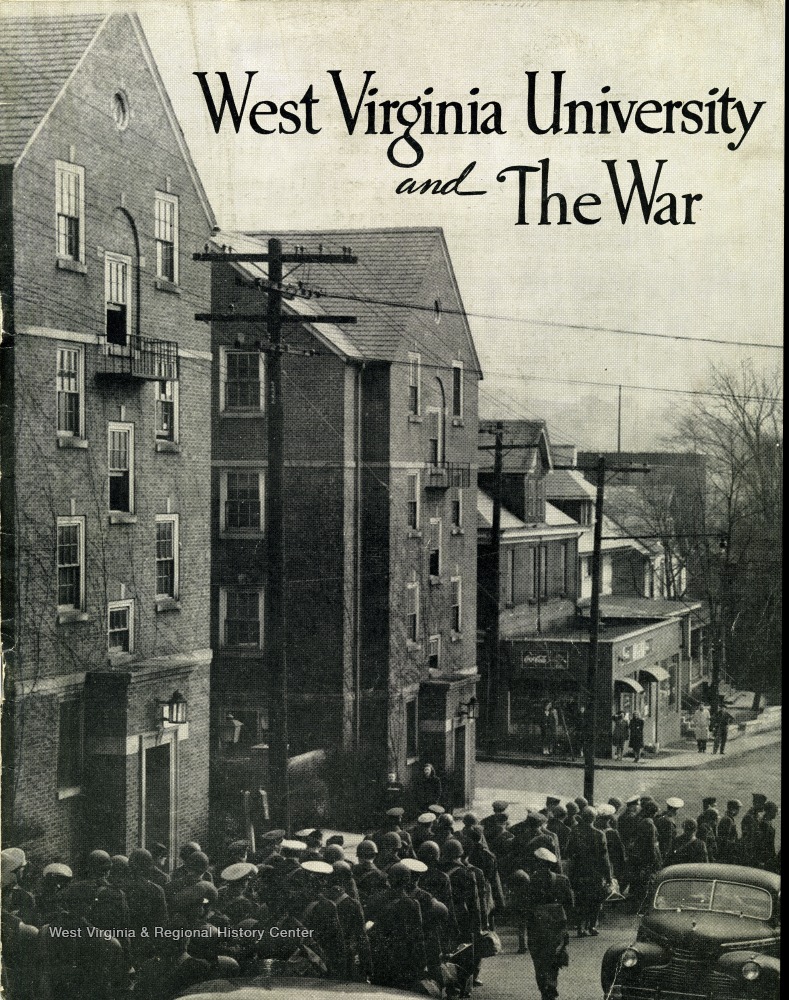

An invaluable source regarding West Virginia University and its efforts during the Second World War is found in Dr. Easton’s own work, West Virginia University and the War, which was published in 1944.11 This piece explores the various ways in which WVU participated in the war effort, including images of students with captions such as “The smiling young lady investigates the setting point of TNT,” descriptions of nursing and first aid training, and information on how Air Corp Cadets trained in the classroom and at the Morgantown Airport.12 Through this source, an image of West Virginia University during this time comes into focus; a bustling campus, filled with not only dedicated students but also livened by the inner workings of service members in various stages of the pipeline that led to active duty and deployment.

Global context deepens our understanding of the changes WVU underwent during this time. By 1942 – the year Scott graduated from WVU – the war in Europe had undergone a number of significant developments. Not only had Germany invaded or allied with almost every nation on the continent – including the defeat of France and the near destruction of Poland – but the Eastern Front had also begun to play out as Germany set her sights on the USSR. The United States had also been pulled into the war despite all efforts to remain isolationist. The Empire of Japan had struck at Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, unknowingly provoking the nation which would go on to be her undoing four years later.13 Thus, by 1943, the Pacific and European theaters were well underway, and the United States had become committed to not only the complete defeat of Nazi Germany but also of the Japanese Empire.

With all of this in mind, it’s understandable why a man in good health and in the position to serve, would enlist. Scott never mentioned in his letters why he traveled to Ft. Hayes on March 19, 1943, with the intention of enlisting in the Army. However, Keenly discusses a number of reasons that young men enlisted, expressing that, “While nationalistic fervor and delusions of military glory influenced a small number of West Virginians, many more found themselves joining the war effort for better economic opportunities and, in a few cases, because of the social pressure applied to young men to perform their patriotic duty.”14 This is to say, while it is plausible that Scott felt a duty to serve on moral or patriotic ground, it is also possible that he felt pressure – as so many others did – to enlist. Regardless of why, Scott’s enlistment on March 19 put him on a path that ended in Germany almost two years later.

Upon enlistment, Scott was sent to Fort Knox. There are several letters from this time that provide insight into his activities and the conditions at Fort Knox. Writing Dr. Easton, Scott remarks, “The army with its usual efficiency and accuracy has sent the [lot] of us West Virginia Tank Destroyers to the wrong camp. We were supposed to go to Camp Hood but oddly enough they sent us to Fort Knox… It is a hell hole… I propose to be transferred.”15 Despite the mishap and Scott’s desire to be transferred, no such proposal was ever approved, and Scott would remain at Fort Knox for almost a year.

In the same letter, Scott mentions Officer Candidate School (O.C.S.), and that his chances of becoming an officer were dwindling.16 With his transfer in limbo and his hopes of becoming an officer fading, Scott turned once again to academia. He writes, “I think I will go down to the Armored [unintelligible] Institute – which claims to offer high school and college courses – and offer my services… you have to do your best and get ahead in this army stuff or they will forget you completely.”17 In this excerpt, Scott demonstrates an understanding of his situation and the army he served in. He learned quickly that he had to make himself marketable. Unfortunately for Scott, it appears this opportunity was a dead end.

His recounts of training at Fort Knox were honest and highlighted some of the challenges soldiers faced long before they reached the front lines. In a subsequent letter, Scott describes, “I am usually as tired as a soldier can be and that is plenty tired. We marched in 115° heat yesterday for 10 miles and lost many men on the way. I lasted by will power more than anything. It was very tough.”18 Not all was lost, however, as he goes on to write, “Had my first chance to lecture today… they asked for a ‘vol’ to give a talk on first aid… didn’t think so much of it, entirely impromptu, but I have been receiving compliments all day since. Guess my days as an assistant have not been wasted.”19 While he didn’t secure the position teaching college courses, Scott made use of his talents while serving at Fort Knox.

In a third letter from 1943, Scott joked, “I am, fortunately, no casualty of the Battle of Fort Knox.”20 In explanation of his absence, he elaborated that he had “been living in the field for three weeks,” indicating that training was beginning to escalate at Fort Knox.21 He also mentioned that he had passed the “O.C.S braid” and hoped that his blood pressure wouldn’t keep him from passing the physical.22 This comment indicates that officer school may not have been out of the picture for Scott.

In a letter written to Dr. Easton in February of 1944, Scott not only confirmed that he would be attending O.C.S., but that he had undergone an operation that required him to return to Morgantown for “a couple of months recuperation period.”23 While the specifics of the operation are unknown, Scott appeared to make a full recovery and proceeded with officer school as planned. One interesting inclusion in a later letter discusses a two week course that Scott participated in, centered around operating military vehicles from “jeeps to medium tanks”.24 This is only a glimpse into the experiences that made up Scott’s time in the army prior to active deployment. In his preparation for war, he was introduced to a myriad of new skills and groups of people. Yet, a constant theme in his letters is a desire to return to WVU and the History Department.

This longing, coupled with idleness while remaining in the states, created a yearning to not only be involved in the activities of Morgantown, but also to join the fight. As Scott mentions at the end of a letter written in the summer of 1944, “You must write me and tell me how the summer goes with you. We know our plan until September or rather October 16 but after that who can say. I presume that if the invasion goes well we may go over about then. In a way I rather hope we do. Looks as if you may be much more right about the war. My prediction was 1945. Shows how conservative I am at 22.”25 He expresses a perhaps confusing sentiment, a combination of longing for his life in Morgantown and a restlessness brought on by the escalation soon to come in the war. In over a year of army service, Scott had been stationed exclusively in the states. A desire to be ‘in the fight’ would be understandable if not expected from those who’d been stuck in basic training and officer school. What Scott didn’t know was that he’d soon be in the fight, one that would take his life less than a year later.

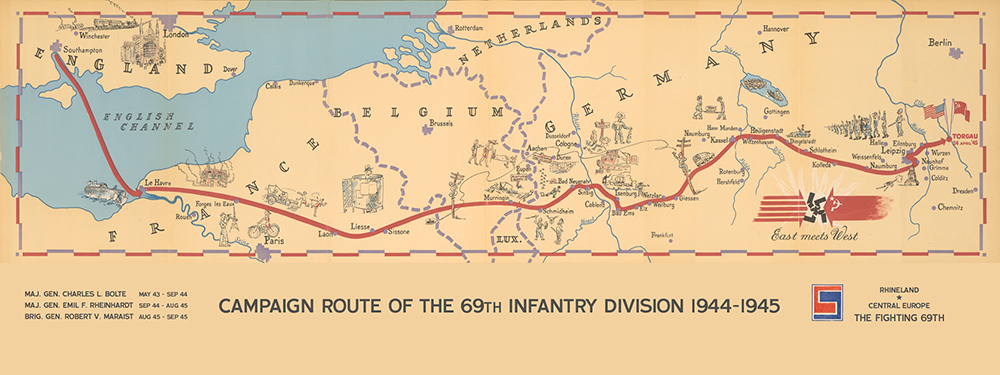

Scott first arrived in Britain near the end of November, 1944.26 His departure is briefly recounted in his final letter to Dr. Easton. He writes, “you seemed surprised about my sudden departure for merry England.”27 As he’d written in the previous letter, Scott’s schedule had been uncertain beyond mid October. Serving as a lieutenant in F Company, 271st Regiment, 69th Division of the First United States Army, Scott was likely “billeted in Winchester Barracks” while stationed in Britain.28 He wasn’t there for long. On January 20th, 1945, the 271st Infantry Regiment sailed across the channel, landing on snow covered Normandy beaches the next morning.29 The Regiment entered Germany on February 10th, 1945, less than a month into their advance across the Western Front.30 Their rapid pace was due to the prior engagements and Allied victories in Western Europe which allowed the Regiment to meet the front as it entered Germany.

Within his final letter, Scott not only recounts the beauty of the German countryside, but also describes his interactions with the German people. He jokes, “German hospitality is not what it might be. One would almost believe that they do not desire our presence here. Oh well… really a pretty good fight up here.”31 With this sentiment, Scott harks on an aspect of the war that is often overlooked, but was pivotal to a soldier’s experience; that being relations with civilians. It was hoped that the German population would be relieved to see the Allies, to be ‘liberated’ from the current Nazi regime. However, as many Allied soldiers discovered, the German population was at best apathetic. Denazification would be a challenge faced by the Allied powers for years after the war ended.32

These being some of Scott’s last written words regarding the war, the rest of his movements up until his death on February 28th, 1945, must be surmised from the records of the 271st Regiment and eyewitness accounts. The Regiment moved through Germany towards what would be their first attack on February 27th, 1945, with the objective of securing a supply route via Hellenthal-Hollerath road.34 Higgins recounts that;

Company F, attacking Buschem and Honningen, was able to take half of Buschem before being pinned down by fire from nearby Honningen, and was ordered to hold its present position for the night… [G Company was then ordered to] close the gap between themselves and F Company. The Third Battalion was alerted that night, but not committed until next day. Next morning, E Company was committed to assist F Company, and the two companies cleared Buschem and went on to take Honningen. Two counterattacks were repulsed in the area.35

This excerpt encompasses not only the first attack that the 271st Regiment engaged in, but also the action in which Scott was killed. With a broad overview of the objective and the stakes, a better picture of the circumstances Scott and his men found themselves in comes together. In their first major engagement of the war, F Company was separated from the rest of the 271st Regiment and pinned down. While G Company attempted in vain to reach them, F Company was on their own. It was not until the next morning that E Company could assist them. Thus, on the morning of February 28th, 1945, Scott and his men felt a moment of relief. E Company had come to aid them in taking their objective despite the heavy resistance. But the price of that victory would be great, as it was for so many actions during the Second World War.

James Kidd, considered one of if not the last person to see Scott alive, sheds light on the specifics of their actions that day. In a letter to Dr. Easton he writes;

Lt. Robert. F Scott and I were commanding the leading platoons of an attacking company in a rapid advance… The men were having a difficult time climbing over the rough ground with a heavy load of ammunition. Enemy machine guns and ‘burp’ guns from our flanks made the going even tougher… I saw Bob about 75 yards to my right at the front of his platoon encouraging his men on… The last time I saw him alive he was turned half around, moving forward at the same time… shouted to his men something like, ‘Come on, can’t you keep up with me, an old man like me?’… The next day… I saw his body, lying at a cross road. It was a typical example of modern war, too terrible to describe for civilized beings.36

Kidd’s description of heavy resistance and machine gun fire line up with the report provided by Higgins. His recount also evokes a sense of detached loss so commonly found in the testimony of veterans. The death of Scott, while devastating, was considered ‘typical’. Kidd simply did not have the time or emotional bandwidth to fully process Scott’s passing at the time or perhaps even afterwards.

A further description of Scott’s fate, one that sheds light on his character, is shared in a letter by Mrs. Scott to Dr. Easton. According to ‘a Major General’;

The fighting from house to house was fierce. One of his men was seriously wounded and was lying in a sunken place in the road which was covered by machine gun fire and in danger of further injury. Without regard for his own safety Lt. Scott passed through the fire to the wounded man and when attempting to return with him was killed by machine gun fire.37

From this account, the circumstances of Scott’s death are even further understood. Not only had he been leading his men onto the road, but he had stopped and attempted to aid one of his comrades despite the immense peril of that action. His bravery and selflessness, even in his final moments, are something that no plaque or medal could ever adequately express. Genuine sacrifice on such a level defines the cost of the Second World War.

It could be argued that considering an individual’s experience in a global conflict does not give an accurate representation of the conflict’s true impact. That is to say, that one person’s story could not possibly define a war that claimed 60 million lives. And while Robert Scott’s story does not address every minute detail of the war or the geopolitics behind it, Scott’s story does encapsulate the tragedy of the Second World War. As James Kidd wrote, “[Scott’s] Silver Star commendation said something about ‘above and beyond the call of duty.’ Such is war.”38 Such a statement supports the idea that Scott’s story, while heroic, was not uncommon. Thus, one man’s story may not define a war, but it can certainly aid in grasping the impact of the conflict on not just an individual but a family, community, nation, or perhaps the world.

When considering legacy, it is often awards and accolades that first come to mind. And while Robert Scott was awarded a Bronze Star and the Silver Star, it feels hollow to remember a person purely based on the medals on their record.39 Scott was more than just a couple pieces of commemorative metal. He was a promising academic, a loving son, and a brave soldier even in the face of death. As Dr. Easton fondly writes;

Bob was one of my best students and an unusually fine fellow, as you know, and I was much upset by his death. It is one of the great tragedies of war that so many young men of promise should have to make the supreme sacrifice at the beginning of careers that would have meant so much to them and to the world.40

Dr. Easton’s emphasis on unknown potential is an important one. What might Scott or the millions of others killed in the Second World War have gone on to do? It’s a difficult question, and one that will never have an answer. Once again, the tragedy of war can be encapsulated in the loss of a single, promising individual, because the unknown potential of all of the lives lost in the Second World War would be beyond comprehension. Robert Scott’s story then, is not one defined simply by loss, but by his unknown potential. And while it is easy to distance oneself from history, whether by the passage of time or changes in society itself, there are themes that are pervasive throughout all time. Especially in an era of uncertainty and division, it is important that stories like Scott’s continue to be told. To remind us that despite differences in lifestyle, political opinions, or simply distant zip codes, everyone has the potential to do something for the betterment of society… and that that potential can be stripped away in the blink of an eye. All of this to say, if you take anything from Robert Scott’s story, it should be that you don’t always know how long you have or where life will take you. It should be one’s goal, then, to explore that potential as fully and freely as one can. Because not everyone gets that chance, and we owe it to those who’ve laid down their lives for our freedom and safety to pursue that potential for the betterment of our university, our nation, and our society.

Notes

1. “Robert F. Scott, Class of 1942”. West Virginia History OnView. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/038857.

2.“Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II,” The National WWII Museum, accessed October 17, 2023, https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/

Research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war.

3. John Higgins, “Trespass Against Them”: History of the 271st Infantry Regiment (Naumburg, Germany, 1945).

4. National Archives, World War II Army Enlistment Records.

5. “Robert F. Scott, Class of 1942”. West Virginia History OnView. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/038857.

6. Letter from Mrs. Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, 1945.

7. Letter From Dr. J.C. Easton to Mr. and Mrs. Scott, March 24, 1945.

8. Letter From Dr. J.C. Easton to Mr. and Mrs. Scott, March 24, 1945.

9. Belmont C. Keenly, “Soldiers and Stereotypes: Mountaineers, Cultural Identity, and World War II,” (West Virginia University, 2009) p.44.

10. “Cover of, West Virginia University and the War’ by J.C. Easton, Associate Professor of History, West Virginia University”. West Virginia History OnView. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/038857.

11. J.C. Easton, West Virginia University and The War.

12. J.C. Easton, West Virginia University and The War.

13. Gerhard Weinberg, A World At Arms: A Global History of World War II.

14. Belmont C. Keenly, “Soldiers and Stereotypes: Mountaineers, Cultural Identity, and World War II,” (West Virginia University, 2009) p.20.

15. First letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.1-2.

16. First letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.2.

17. First letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.2-3.

18. Second letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.1.

19. Second letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.2

20. Third letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.1.

21. Third letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.1.

22. Third letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, p.4.

23. Letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, February, 1944, p.1.

24. Vehicle training letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, 1944, p.1.

25. Invasion letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, Summer, 1944, p.2.

26. Higgins, “Trespass Against Them.”

27. Final letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, February, 1945, p.1.

28. “Robert F. Scott, Class of 1942,” West Virginia History OnView; John Higgins, “Trespass Against Them”.

29. Higgins, “Trespass Against Them.”; John Grehan, Liberating Europe: D-Day to Victory in Europe, 1944–1945 (Barnsley, South Yorkshire: 2014) p.182.

30. Higgins, “Trespass Against Them.”

31. Final letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, February, 1945, p.1.

32. Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (New York: The Penguin Press, 2005), p.57.

33. “69th Infantry Division – The Fighting 69th”. US Army Divisions. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.armydivs.com/69th-infantry-division.

34. Higgins, “Trespass Against Them.”

35. Higgins, “Trespass Against Them.”

36. Letter from James Kidd to Dr. J.C. Easton, May 8, 1945, p.1.

37. Letter from Mrs. Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, April 30, 1945, p.1.

38. Letter from James R. Kidd to Dr. J.C. Easton, May 8, 1945, p.1.

39. Letter from James W. May to Mr. and Mrs. Scott, 1945, p.1.

40. Letter from Dr. J.C. Easton to James Kidd, May 23, 1945, p.1.

Bibliography

Easton, J.C., West Virginia University and The War. Morgantown: West Virginia University, 1944.

Final letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, February, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Final Report: 1951 Army ROTC Armored Summer Camp. Fort Belvoir; United States Army Publishing Directorate, 1951.

First letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Higgins, John. “Trespass Against Them”: History of the 271st Infantry Regiment. Naumburg, Germany;1945.

Invasion letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, summer, 1944, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

John Grehan, and Martin Mace. 2014. Liberating Europe: D-Day to Victory in Europe, 1944–1945. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=b388bcba-db0b-3ff2-aba0-7c1e15f812d5.

Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. New York: The Penguin Press, 2005.

Keenly, C. Belmont. “Soldiers and Stereotypes: Mountaineers, Cultural Identity, and World War

II.” PhD diss., West Virginia University, 2009.

Letter from Dr. J.C. Easton to James Kidd, May 23, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from Dr. J.C. Easton to Mrs. Scott, May 7, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from Dr. Easton to Mr. and Mrs. Scott, March 24, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from James W. May to Mr. and Mrs. Scott, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from James R. Kidd to Dr. J.C. Easton, May 8,1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from James R. Kidd to Dr. Clark Easton, May 8, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from Mrs. Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, 1945, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV, War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, February, 1944, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

National Archives. World War II Army Enlistment Records. Research Group 64. National Archives: Access to Archival Databases (AAD), 2002. Digital: https://aad.archives.gov/aad/record-detail.jsp?dt=893&mtch=2&cat=WR26&tf=F&sc=24994,24995,24996,24998,24997,24993,24981,24983&bc=,sl,fd&txt_24995=Robert+Scott&op_24995=0&nfo_24995=V,24,1900&cl_24996=54&op_24996=null&nfo_24996=V,2,1900&cl_24998=039&op_24998=null&nfo_24998=V,3,1900&rpp=10&pg=1&rid=1141309&rlst=1141309,6038806.

“Research Starters: Worldwide Deaths in World War II,” The National WWII Museum. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/students-teachers/student-resources/research-starters/research-starters-worldwide-deaths-world-war.

“Robert F. Scott, Class of 1942, West Virginia University, from St. Albas, W. Va.” West Virginia History OnView. Accessed November 5, 2023. https://wvhistoryonview.org/catalog/038857.

Second letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Third letter from Robert Scott to Dr. Clark Easton regarding Fort Knox, 1943, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Vehicle training letter from Robert Scott to Dr. J.C. Easton, 1944, A&M 2324, Easton WWII Material, WV War History Commission Recs, West Virginia and Regional History Center, West Virginia University Libraries, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Weinberg, Gerhard. A World At Arms: A Global History of World War II. Cambridge; Cambridge University Press, 2005.

“69th Infantry Division – The Fighting 69th”. US Army Divisions. Accessed December 12, 2023. https://www.armydivs.com/69th-infantry-division.