Black and White and Bruised All Over: The Violent World of Newspaper Editors in Gilded Age and Progressive Era West Virginia

Posted by Mary Alvarez.November 7th, 2022

Written by Luke Masa, WVU History Doctoral student & National Digital Newspaper Grant Assistant

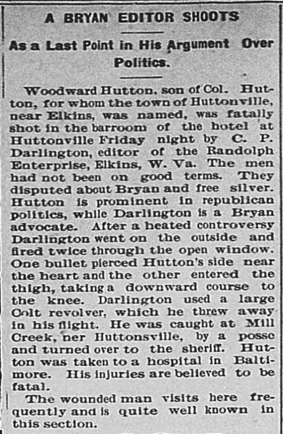

In July 1900, just after the Randolph Enterprise newspaper moved from Beverly to Elkins, its newly minted editor C.P. Darlington got into an argument with a man named Woodward Hutton. Hutton was the son of a Colonel, and nearby Huttonsville was named for his ancestor John. And despite being four years out from William Jennings Bryan’s loss to William McKinley, Darlington and Hutton were said to have been vigorously debating the question of “free silver” – that is, should U.S. currency be backed solely by gold, or should silver be exchangeable as well? Darlington, a Democrat like Bryan, was for free silver, Hutton, a Republican, against. While it is unclear precisely what each said to the other, the argument ended when Darlington shot Hutton, who later died from the wound.

Violent incidents such as this one were far from unheard of among the men who edited and managed West Virginia’s newspapers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In writing title essays for the National Digital Newspaper Program’s website Chronicling America, I have come across numerous examples of scuffles, scrapes, jabs, and barbs which transcended the page and moved into the realm of physical altercation. For instance, Martinsburg’s F. Vernon Aler, an acerbic corporate lawyer and amateur historian, tried his hand at the printing business twice, once in the late 1880s and again in the early 1890s. His first attempt, the Martinsburg Gazette, folded shortly after he was arrested following a fist fight with another young man on the city’s streets. And he left his other paper, the World, after exchanging blows with the President of the local National Bank.

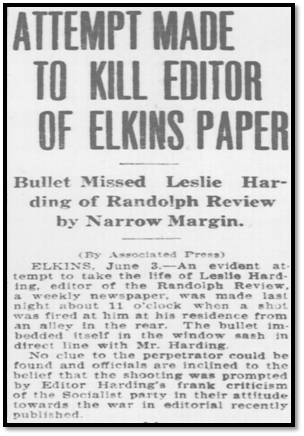

Some twenty-odd years later, with the martial fervor of World War I in full swing, the associate editor of the Randolph Review, Leslie Harding, was shot at through the window of his home. Though unscathed, he immediately blamed “a socialist or some other German sympathizer”, as apparently, he thought his patriotic invective sufficiently notable to warrant such an attempt.

Earlier that decade, during the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek strike of 1912-1913, the Pocahontas Times called for anyone caught “tear[ing] down the flag” to be “[shot]…on the spot.” As the above anecdotes attest, rhetoric of this sort was not always merely rhetorical. This was a period of great upheaval throughout the state, and not just for industrial workers. Unfortunately for a certain subsection of the professional class, the pen was not always mightier than the sword. Or gun, for that matter.