The War in Words: Union and Confederate Civil War Military Camp Newspapers in Charleston, Western Virginia

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.March 14th, 2017

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Rare Book Librarian

Civil War Military Camp newspapers are few and far between, but the news they printed is still valuable to us today. As troops came into town, if there were newspapermen among the regiment, they often took over the press to print their own regimental newspaper. The press may have been abandoned by fleeing residents or it may have been taken over by the troops, in any case, these rare survivors of Civil War news often reflect the movement of troops, the availability of soldiers skilled as newspapermen, and the proximity of a usable press. These papers document the continuing flux of the military during the war, the development of western Virginia as it strives for independence from Virginia, and the need to support and bolster troop morale. Few copies survive and those that do are extremely valuable for their reports of daily life, the publication of popular songs and humorous sketches, and reports on battles, politics, and troop movements.

The Confederate occupation of Charleston, Virginia (now West Virginia) in September and October of 1862, lasted a mere six weeks before the Union regained control of the area. However brief the occupation, two newspapers flourished amidst the competing camps: the Knapsack and the Guerilla.

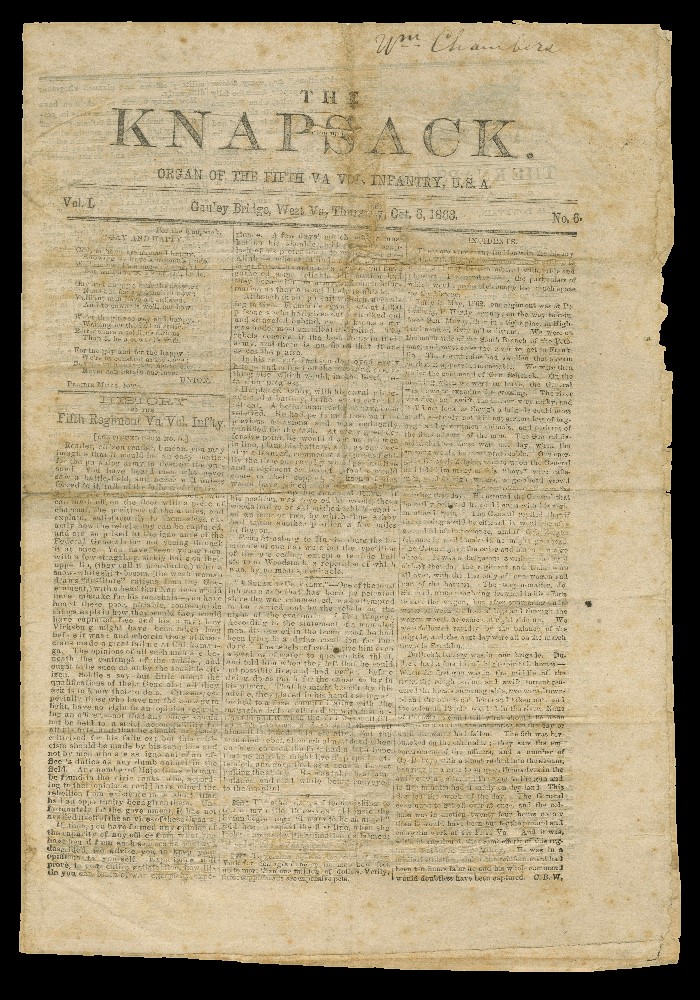

The Knapsack, a Union newspaper published by the 5th Virginia Volunteer Infantry and the Guerilla, a Confederate newspaper published by the Associate Printers of the Confederate Army, waged the war, not just on the battlefield, but also on the printed page.

WVU holds original copies of the Knapsack and the Guerilla. Issues of the Knapsack and the Guerilla are currently being digitized and will be available on the Library of Congress site, Chronicling America, at the close of the present NEH grant cycle.

On August 22, 1862, Confederate cavalry rushed into the Union supply depot at Catlett’s Station, Virginia, and captured a small number of Union soldiers and a vast amount of Union supplies. Included in the spoils of war were the personal belongings of Union Major-General John Pope, pictured below, commander of U.S. forces in northern Virginia. Aside from capturing the general’s uniform, horses, and money, the Confederate cavaliers also uncovered a dispatch-book of General Pope, reported to superiors as containing “information of great importance to us, throwing light upon the strength, movements, and designs of the enemy.”

The captured dispatch book quickly made its way to Confederate authorities in Richmond. On August 29, Confederate Secretary of War George Randolph fired off a note to Major-General William Wing Loring. Randolph informed Loring that “Pope’s letter-book has been captured,” and the Union forces in the Kanawha Valley of western Virginia were being shifted elsewhere. Grasping this opportunity, Secretary Randolph ordered General Loring to “Clear the valley of the Kanawha and operate northwardly to a junction with our army in the valley.” The Confederacy was set to invade West Virginia.

On September 6, Loring’s forces set out on their expedition. Over the next week, the Confederate army, approximately 5,000 men —including many Virginians who hailed from the western region of their state—fought a series of engagements with the Union. Today the clash of opposing forces on September 13th is recognized as the Battle of Charleston. “Capturing the town after a stout resistance from the enemy,” General Loring settled into an occupation of Charleston and secured the surrounding region.

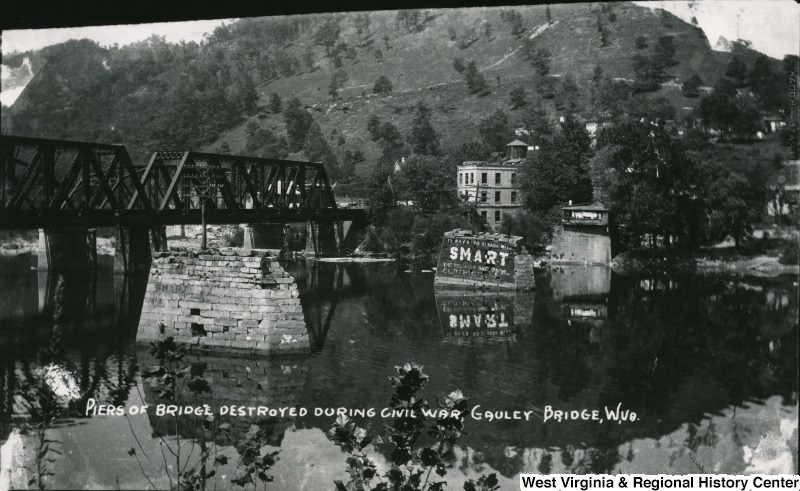

Much of the action centered on the tiny town of Gauley Bridge. Settled in the early 1800’s, Gauley Bridge, prior to 1822, was originally known as Kincaid’s Ferry. The present name for the town came from the wooden covered toll bridge built in that year as part of the James River and Kanawha Turnpike. Located at the confluence of the New and Gauley rivers, where the Gauley and New meet to form the Kanawha, the town of Gauley Bridge overlooks the large, lake-like pool formed by the falls of the Great Kanawha Valley just one mile downstream. During the Civil War, Gauley Bridge was captured and recaptured three times; during these actions wooden bridges across the mouth of the Gauley were burned twice.

The region outside of Charleston offered a valuable commodity to soldiers and regiments during the Civil War: salt. The Kanawha Salines was an area of active salt production and salt was desperately needed to preserve the meat needed to feed soldiers.

The Kanawha Salines, the name given the salt fields of West Virginia, travel along both banks of the Kanawha River until the waters reach Charleston, a distance of approximately ten miles. The origin of the region can be traced back to the earliest times, 600 million years ago, to an ocean that predates the Atlantic, called the Iapetus Ocean.

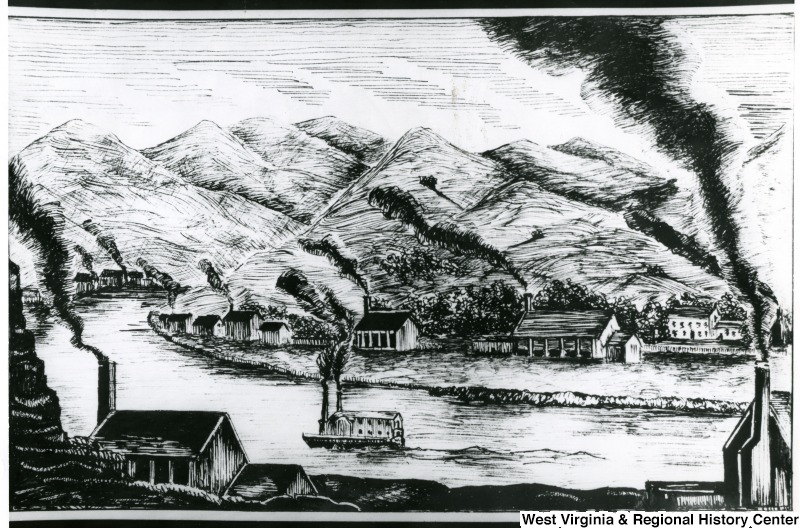

This drawing below shows the buildings used in salt manufacturing. As early as 1808, the Kanawha Salines were put to production and a salt making and refining industry was developed by Joseph and David Ruffner, who drilled for brine and established furnaces to process it. This area, particularly around present day Malden, West Virginia, where the salinity was at a high point, would develop into an important resource for the meat packing industry. By 1815, furnaces dotted the landscape, leading to the development of the area as one of the great salt manufacturing regions in the United States, as the use of salt to pack meat for shipment ensured it would arrive to destinations in good condition.

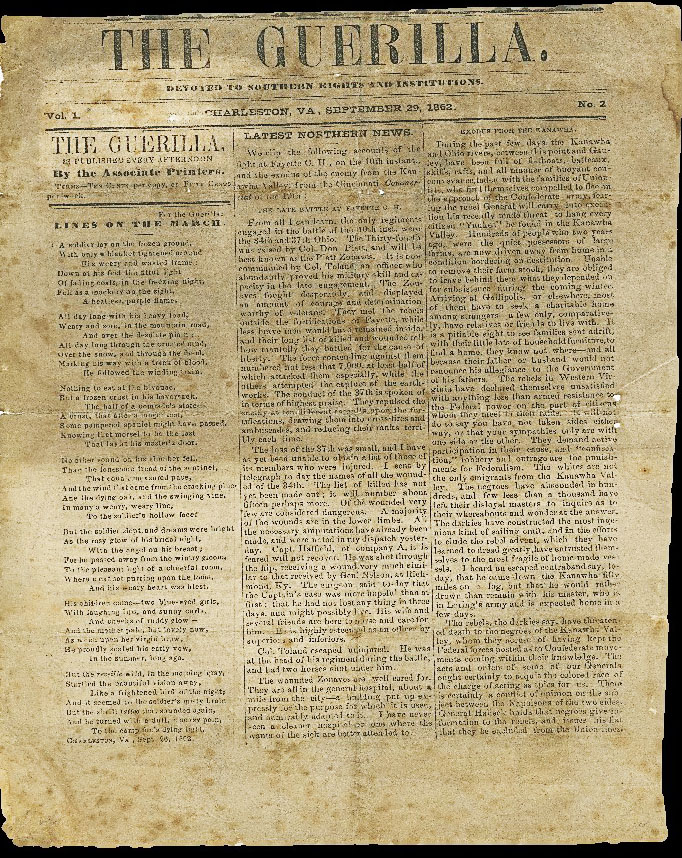

Once the Confederates settled into occupation one of their first matters of business was to publish their own newspaper, the Guerilla, whose motto beneath the masthead states that the Guerilla is “Devoted to Southern Rights and Institutions.” The Guerilla was designed to keep Charleston’s citizens informed during this time and to promote the occupying forces as liberators, rather than occupiers. Published every afternoon by the Associate Printers, the newspaper sold for ten cents a copy, fifty cents a week.

In a proclamation published in the paper’s pages, General Loring declared the army’s desire “to rescue the people from the despotism of the counterfeit State Government imposed upon you by Northern bayonets, and to restore the country once more to its natural allegiance to the State. We fight for peace and the possession of our own territory…”

Other articles urged local merchants to open their stores to the Confederate soldiers, and likewise to set aside their “scruples about taking Confederate money.” Unionist Virginians were encouraged to defect to their Confederate counterparts.

Federal forces once again moved into the area following the creation of the new state of West Virginia on June 20th, 1863. That fall, the soldiers of the Fifth West Virginia Infantry found themselves stationed at Gauley Bridge in their newly-minted state.

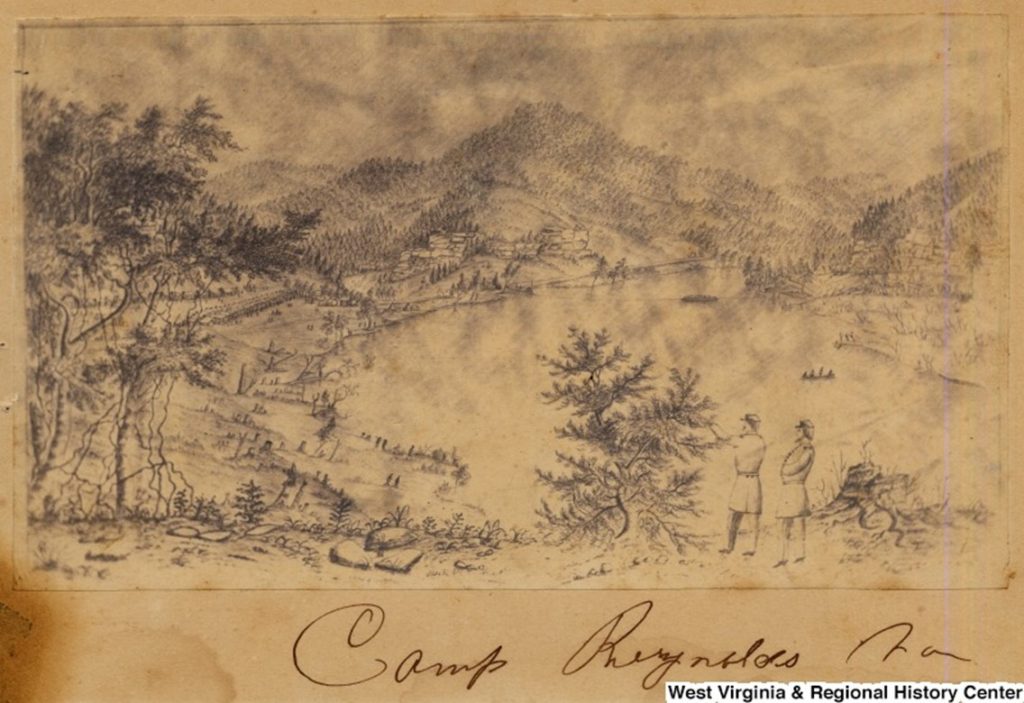

Several Army camps were stationed just below the Chesapeake and Ohio Depot site near the mouth of Ferry Branch on the Kanawha River. One of these was known as Camp Reynolds. The sketch above shows Camp Reynolds, which served the Union Army at Kanawha Falls with 56 cabins and parade grounds for 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry commanded by Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes and Lieutenant William McKinley, both future U.S. presidents.

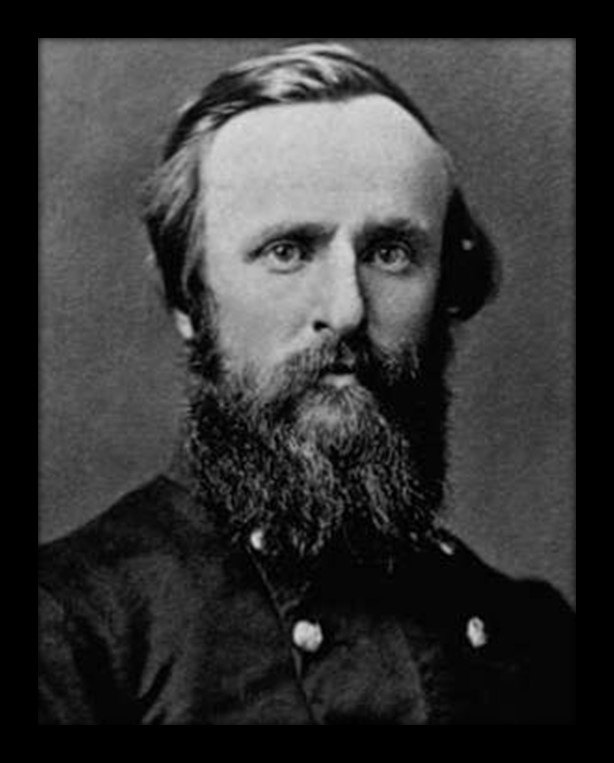

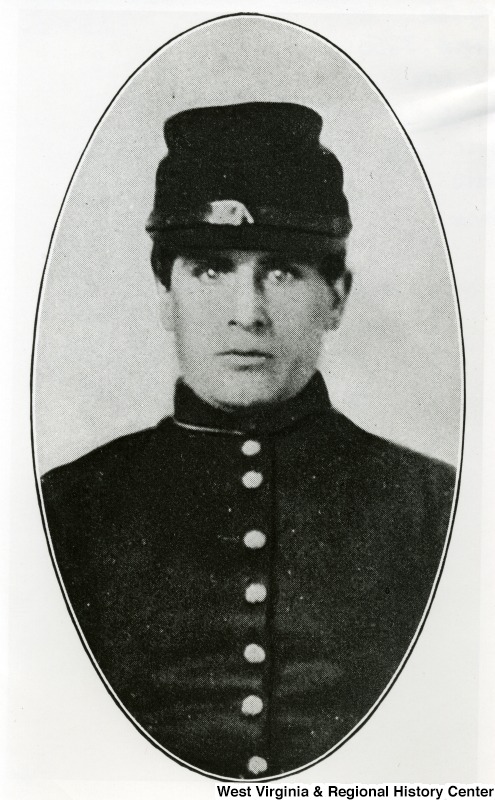

Portraits of Rutherford B. Hayes, above with beard, commanding officer of the 23rd Ohio Infantry, which had been stationed in Charleston since March 1863 and Private William McKinley, Jr., above without beard, of Company E, 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. McKinley, a Poland, Ohio native, was a mere 18 years old. This photo was probably taken at Camp Chase, Ohio before he left for the West Virginia front.

McKinley, a fellow Ohioan, started the war as a private, but earned a battlefield commission to second lieutenant for showing courage and initiative during the Battle of Antietam. He rose to the rank of major by the time the war ended, and later, followed Hayes to the White House as the 25th president.

Proving to be a relatively peaceful posting, the men promptly set about establishing a regimental newspaper. Having formed the Fifth Virginia Publishing Association, they soon began issuing copies of the four-page Knapsack every Thursday morning at five cents a copy, 15 cents a month and held an active and widely distributed subscriber base for its short duration. Although only published for a few months, the paper illuminates much about soldier life and the politics of war. Within its pages, the Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, still a newspaper of note for West Virginia, described the Knapsack as a “spicy little sheet.” WVU holds the Thursday October 8, 1863, Vol. 1, No. 6 issue.

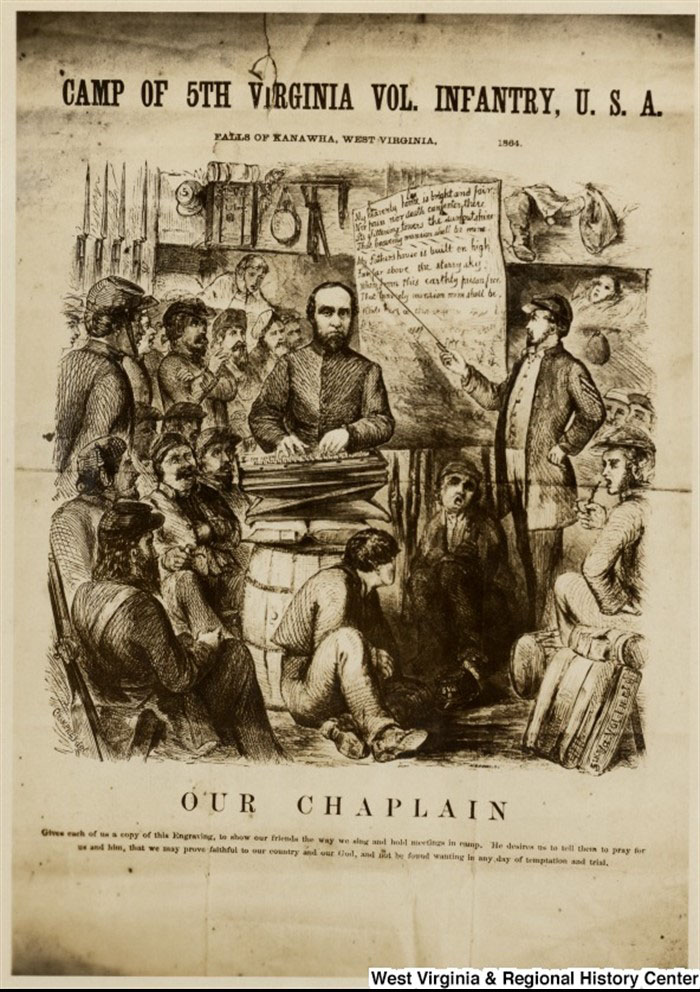

The 1864 engraving of the Camp of 5th Virginia Volunteer Infantry, below, portrays the soldiers, singing, playing music, and holding a religious service. “Our Chaplain Gives each of us a copy of this engraving, to show our friends the way we sing and hold meetings in camp. He desires us to tell them to pray for us and him, that we may prove faithful to our country and our God, and not be found wanting in any day of temptation and trial.”

The engraving illustrates an important facet of the October 8, 1863 issue of the Knapsack which reports on the “schedule of religious services, praised the temperance of the soldiers in camp, and lamented their prolific profanity.” The pages of the Knapsack were filled with the good conduct of the men – with one exception – they were notoriously profligate users of foul language.

On the subject of profanity, the Knapsack states, “it would be well for those persons addicted to this ungentlemanly habit to consider one moment this fact, that at some time they will again return to civil life, and be seeking the society of ladies; then they will find it difficult indeed to abstain from the vulgar habit of swearing, and we presume no gentleman would like a reprimand or be sneered at on account of giving way to a habit.”

You can read both of these newspapers and others at the West Virginia and Regional History Center. Also, all known Civil War Military Camp newspapers held at WVU will be digitized and available free to read and download from the Library of Congress site, Chronicling America, thanks to grant funding from the national Endowment of the Humanities.

Resources:

- Images: All images from West Virginia History OnView, West Virginia and Regional History Center

- Camp Reynolds – West Virginia Historical Markers: http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM2M5A_Camp_Reynolds

- Early drawing of the salt works in the Kanawha Valley. AM 2112: J.Q. Dickinson Collection

- Charleston Gazette-Mail: “Fort Hill’s Fort: City’s Civil War Citadel Mostly Forgotten,” http://www.wvgazettemail.com/article/20140429/gz01/140429229

- Civil Discourse History Blog: http://www.civildiscourse-historyblog.com/blog/2016/3/7/a-very-spicy-little-sheet-the-knapsack-a-soldiers-newspaper-and-the-politics-of-war

Special thanks to Zac Cowsert for sharing his research and his Chronicling America essays for the Knapsack and the Guerilla.