Challenges of Fragile WWII Era Films

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.August 21st, 2017

Blog post by Jane Metters LaBarbara, Assistant Curator, WVRHC

The WVRHC is more than a fantastic repository of the history and culture of West Virginia and the central Appalachian region—we are the Special Collections division of the WVU Libraries, so we also preserve selected materials beyond our state and regional scope. This is a story of some of those out-of-state materials—56 reels of 16mm motion picture film that have nothing to do with Appalachia.

I picked up these films from the Potomac State College library in 2014. The library director at the time told me that the films had been in the library since at least 1986, with no indication of where or who they had come from or whether they had a connection to Potomac State College. PSC librarians gave the films to the Center so we could try to identify them, preserve them, and make them accessible. Each film was housed in a plastic case, and some of those were carefully cataloged in a wooden box. The labels on the film cases indicated World War II subject matter, and those labels formed the foundation of the collection’s contents list, available online.

In the photo above, you can see the effort that a previous owner went to in order to keep the photos organized.

In addition to our lack of information about the creation of these films and how they got to Potomac State College, we faced a few other challenges with these films.

Challenge 1: the ravages of time

Film doesn’t last forever, and these films smell because they are decaying. The smell may be an indication of vinegar syndrome, which is the slow chemical decay of acetate film that causes this vinegar-y smell and causes the film to shrink and become brittle. Alternatively, if the smell is more like mothballs, the film is diacetate, but still decaying. Some of the films are more delicate than others, with brittle spots, missing sprocket holes, etc.

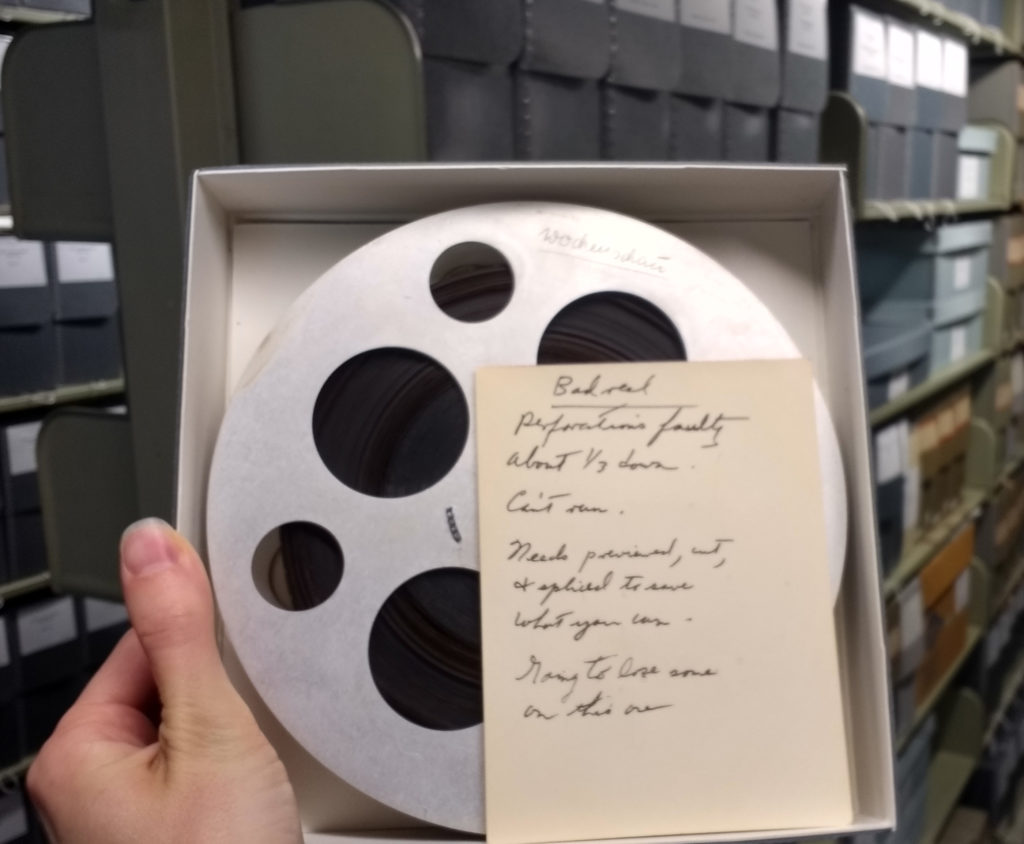

Some reels came with notes, like the one above, which says “Bad reel. Perforations faulty about 1/3 down. Can’t run. Needs previewed, cut, and spliced to save what you can. Going to lose some on this one.”

Considering how delicate the films are AND the fact that we don’t know how unique or rare they are, we decided not to run them through a regular film projector at normal speeds to view them. We would have to find a less physically stressful way to learn about these films. This led us to…

Challenge 2: viewing fragile film

I began looking at a film frame by frame, by putting it on the reel winder/light table contraption that we generally use to fix microfilm that’s been wound backwards, then viewing it through a magnifying glass. I realized that viewing the first frames of each reel, in hopes of finding producer and title information, was going to be time-consuming.

Above you can see my Instagram post of our second set-up, which was a step up from the microfilm reel winder I had started with. I had a great volunteer who worked with this setup to research the first few films. Later, we were able to add a microfilm reader screen, which was easier on the eyes (and necks) of the two students and one volunteer who worked with it.

Challenge 3: language barrier

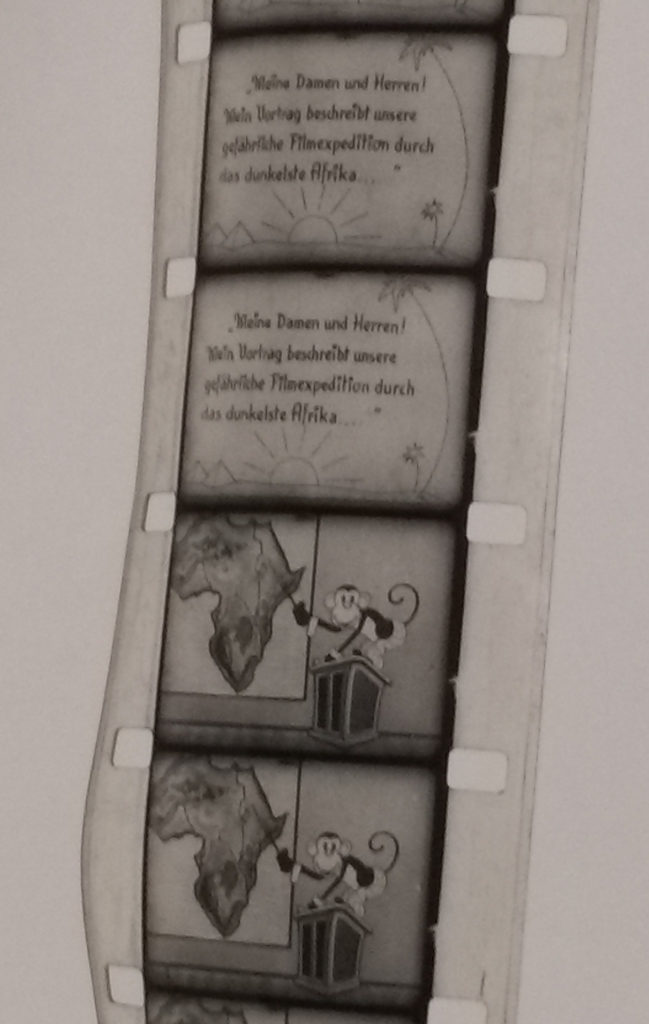

Most of the films are live-action, but one is animated.

Text on film: “Meine Damen und Herren! Mein Vortrag beschreibt unsere gefahrliche Filmexpedition durch das dunkelste Afrika…”

Loose translation: “Ladies and gentlemen! My presentation will describe our dangerous film-expedition through darkest Africa…”

None of these films have sound, but a lot of them have frames of German text. While Google Translate can help us a bit with figuring out the overall subject of a film, looking for materials that are most likely held in the archives of another country is a challenge I’d never faced before, and is tougher than I thought.

Why bother?

When we first acquired these films, I was excited about the possibility of having all 56 reels digitized so WVU classes could use them. I can see these films being useful in German language courses, film courses, history classes on World War II, classes on racism and propaganda, and more. It would be fantastic to have more students in our reading room, discussing the historical significance of these valuable primary sources. Continued study of the rise of the Nazi party and their particular brand of racism seems especially important in light of the recent white supremacist/white nationalist rally and counter-protest in Charlottesville, VA.

My enthusiasm for making these materials accessible was tempered a bit when I got estimates for how much it would cost to digitize each reel. However, if we take no action with these films, they cannot be used by patrons and eventually they will degrade to the point that they cannot be copied. If we cannot make them available, what is the point in keeping them?

To balance the cost of digitizing these films with our mission to allow people to access them, my colleagues and I decided to try to determine the uniqueness of these reels. In theory, if nobody else has them, or if there are only a few copies, creating and preserving a digital copy would be a worthy use of our funds. Unfortunately, I have no subject knowledge in the area of 1930s and 1940s German newsreels, so I looked for other experts.

One of the logos on reel 6–I haven’t yet identified the company that it corresponds to.

I found that the US Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Steven Spielberg Film and Video Archive has a copy of one of our films (except theirs has sound!), so I thought they might be able to offer some advice. After looking over the list of titles that had been affixed to the film canisters, they told me that most of the films are probably not rare because they are official newsreels, and they are likely held within other repositories or archives, such as the Bundesarchiv in Germany or the U.S. National Archives.

However, three of the films were interesting enough that the US Holocaust Memorial Museum was willing to digitize them for us and provide access to them on their film collection website. Click the links below to view the films–they range from 8 to 15 minutes.

Reel 14: “Bobsledding; Soviet War Memorial”

Reel 15: “Soviet War Memorial; atomic bomb explosion”

Reel 20: “Funeral for Werner von Fritsch; Ciano motorcade; Hitler Youth training; Polish Jews”

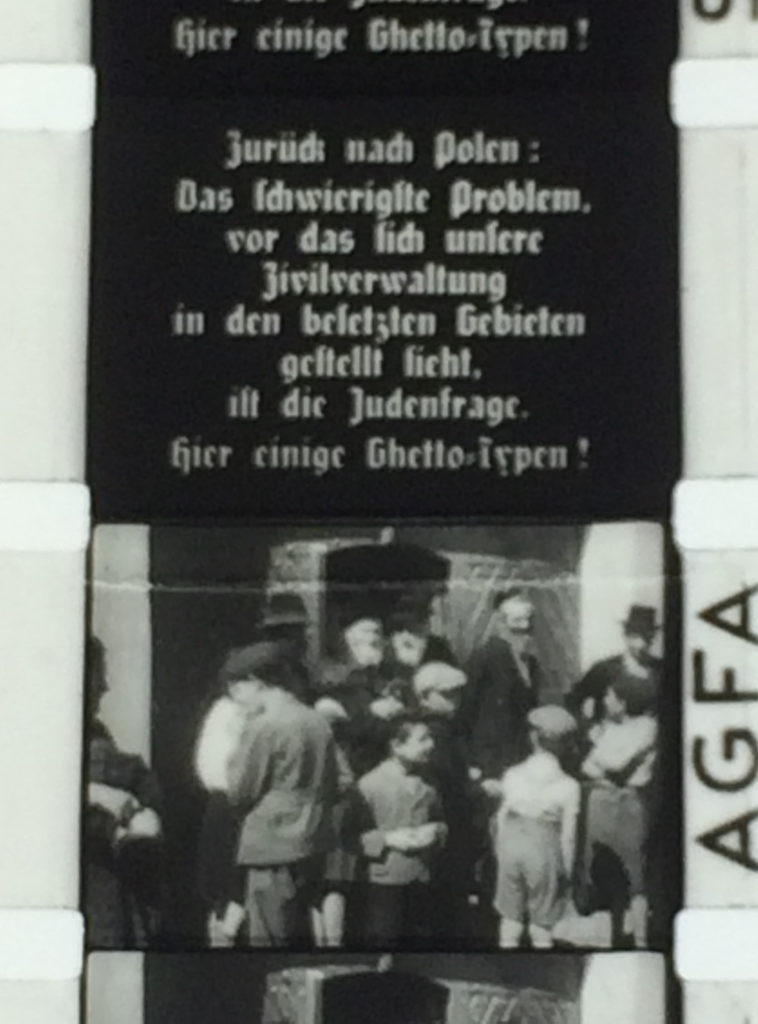

Above are frames from reel 20, one which was digitized by the USHMM.

Text on film: “Zurück nach Polen: Das schwierigste Problem, vor das sich unsere Zivilverwaltung in den besetzten Gebieten gestellt sieht, ist die Judenfrage, hier einige Ghetto-Typen!”

Loose translation: “Back to Poland: The most difficult problem facing our civil administration looks provided in the occupied territories, the Jewish question, here’s some ghetto-types!”

Since then, I have had a succession of wonderful volunteers and student workers carefully reviewing films to see if we can locate other physical and/or digital copies of these films. My next step will be a review of my students’ research, and a discussion with my colleagues about how we’d like to move forward with this collection of potentially valuable research materials.

If you are interested in learning more about these films, or if you want to participate in this project, feel free to contact me at jane.labarbara@mail.wvu.edu.