Ancella Bickley Collection Highlights African American Teachers and School Integration

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.May 14th, 2019

Blog post by Lori Hostuttler, Assistant Director, WVRHC.

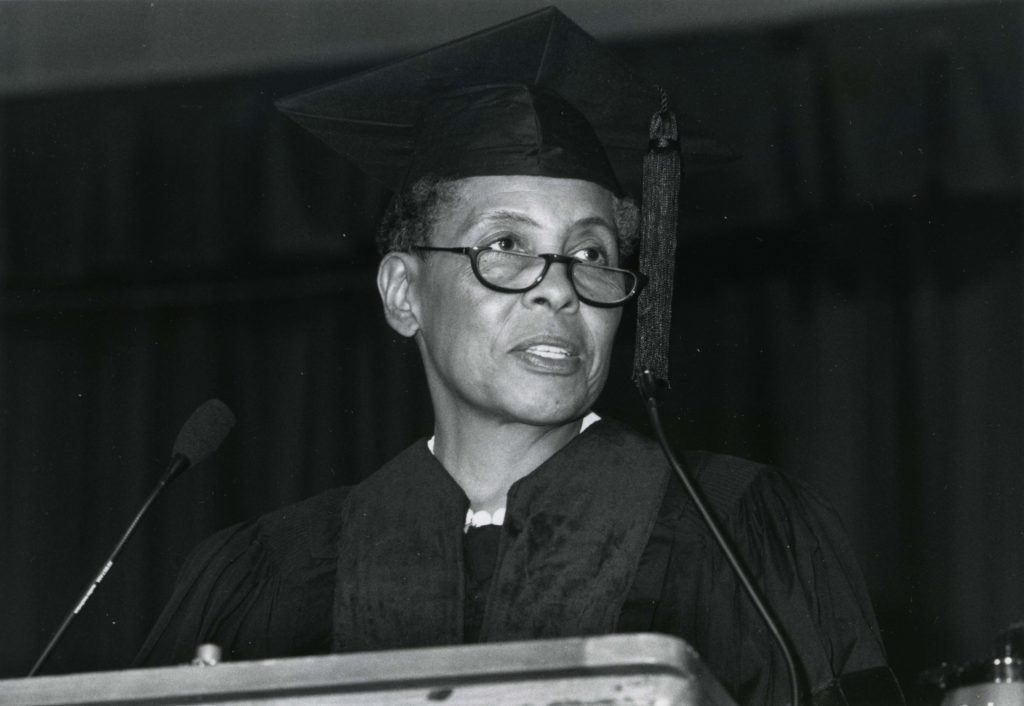

Dr. Ancella R. Bickley is a celebrated author, historian and educator from West Virginia. The Ancella Bickley Research Papers (A&M 4208) held at the West Virginia & Regional History Center document her life, work, and service to the public, especially her research and writing on topics of African American history.

Ancella Bickley speaking at Marshall University commencement in 1990. Image from the Bickley Collection.

One of the projects recorded in her papers are interviews of black women teachers in West Virginia that she undertook with Dr. Rita Wicks-Nelson. The interviews are part of Series 4, Interviews and Oral History Interviews—Black Teachers, 1955-2011, and were completed during Bickley and Wicks-Nelson’s time as Rockefeller Scholars-in-Residence at Marshall University. The series includes transcripts of the interviews, correspondence with interviewees, as well as background information about the women. Additionally, the project files contain administrative records about the project and scholarly articles by Bickley and Wicks-Nelson that draw conclusions from the interviews.

The teachers interviewed came from three regions of the state: North-Central West Virginia (Marion County), the Eastern panhandle (Jefferson County), and South/Southwest West Virginia (Cabell, Kanawha, Logan, Fayette, McDowell, and Mercer Counties.) Most had attended black schools and graduated from black colleges. All taught in public schools and three became principals. The teachers ranged in age from 54 to 92 years old at the time of their interviews. They grew up in times when racial segregation was the norm. Bickley notes that “over time, they became more aware and less accepting of racism. Among the profound changes they personally experienced was, of course, change in the educational system.”

Faculty at Douglass High School in Huntington, W. Va., ca. 1919-1920. Image from WV History OnView.

The interviews provide insights into integration of public schools in West Virginia from the teachers’ perspectives. As the school systems combined white and black schools, African American teachers moved to previously all white schools, but not all black principals were given new assignments. The transferred teachers had mixed experiences – some were treated well, while others were set up to fail – with principals, parents, and colleagues. The teachers noted pros and cons for their students as well. Integration provided better supplies and equipment and enabled a broader curriculum. At the same time from the teachers’ perspectives, black students experienced poorer academic performance, fewer opportunities for getting involved in school activities, and a loss of history and culture that was embedded in their school buildings. Overall, most participants were disappointed in the disparity between the promises and realities of integrated schools.

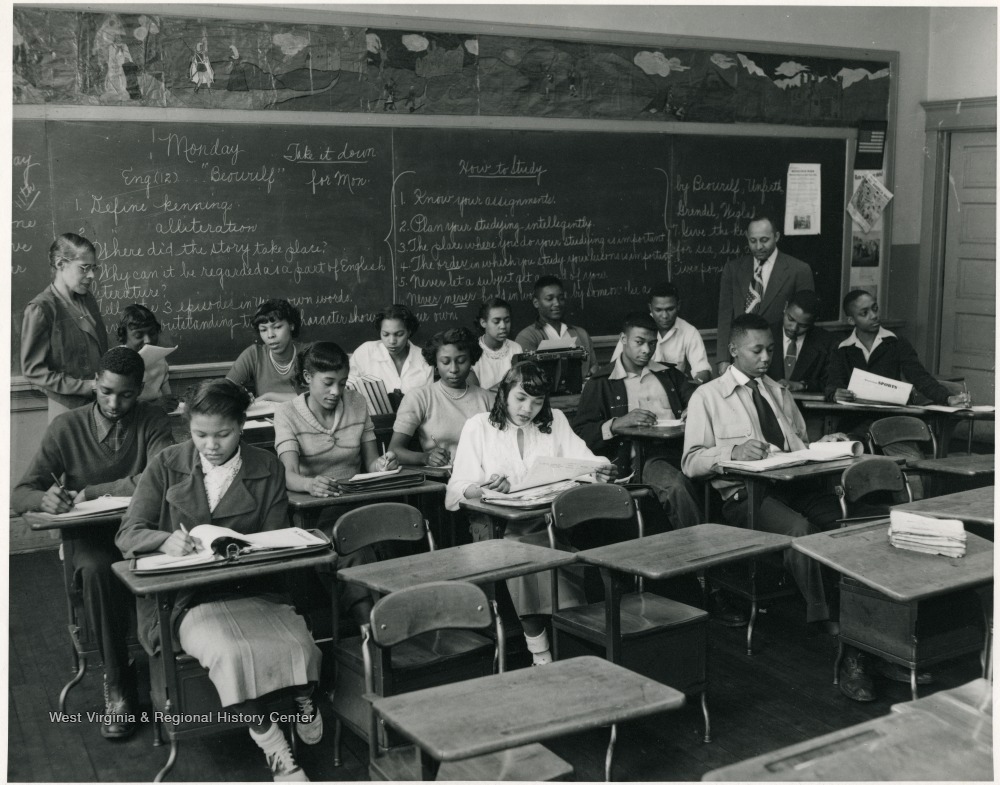

Students and teachers in class at the Kimball Negro High School in McDowell County, February 1950. Image from WV History OnView.

Selected quotations from the teachers illustrated the mixed feelings and experiences regarding integration. Nancie Smith Robinson shared her feelings of alienation from her new colleagues:

“I’ve always been kind of a private person and I just, I wasn’t friendly with the teachers [at Jefferson Elementary School, an all-white school]. I just didn’t try to be friendly. I wasn’t mean to them or anything but I didn’t want to be [friends]—I just wanted to do my work, do my job, and come home. And that’s what I did…[the school] had a bowling team. Well, instead of them asking me—it was the teachers—instead of them asking if I wanted to be on the bowling team and give me the right to refuse or whatever, they didn’t. They would sneak off in the evenings like they weren’t going anywhere. And I never heard anything about it until I heard from one of the patrons at [the bowling alley], wanted to know why I wasn’t on the bowling team. I didn’t even know they had one. And then another thing, like they would have birthday parties for themselves and they wouldn’t tell me anything about it. And I just happen [sic] to go down the cafeteria and there they were after school having a party…And uh, I, I just, after that I just didn’t try to make friends with any of the teachers at [the school].”

Velma Twyman recalled difficult experiences with parents:

“I can remember one [parent], and this was not my first year there. But she had had a crisis in her family. And she came down, she came to my room, crying. I mean she was broken up…I don’t remember what had happened. Had she just lost somebody, or one of her children was really ill? Something. Anyway, I can remember putting my arms around her and consoling her. And all of a sudden, she thought about who I was, and she did one of these numbers [dropped her arms and jumped back over from her]. I just stepped back, and, and let her go…my problem was mostly with parents. And I can remember being in the grocery store and one of my students running up to me, and her mother in a strong voice saying, ‘Come here!’ And there was another time in the grocery store, one of my kids saw me and said, ‘Mom, Mom…There’s [my teacher].’ The mother said–, never turned one way or the other.”

Other teachers received support in their new schools. Fannie Ashe Thomas described the actions of her principal that eased relationships with parents:

“The first year I went to Fayetteville I was the first black teacher there. And the principal was standing there with me at the door that morning. I wondered why he kept standing there with me. Word had gotten around, this black teacher’s coming. And here came this lady with her little boy. And she said to him, ‘I hear my son’s going to be in a black woman’s room. I don’t want him in there. He’s not used to black folks.’ Mr. Thomas said, “Now this is a good chance for him to get used to them, because he’s going to be right in [my] room.’ He had all the names on the door, the kids who were in my room. She got to be one of my best friends before school was out.”

The Ancella Bickley Papers shed light on the lives and experiences of African American teachers in West Virginia during a time of profound change. They are open to the public for further research.

Sources:

Many of the conclusions about integration discussed in this blog come from the following paper. Ancella Bickley and Wicks-Nelson, “Mosaic in Black and White: Black Teachers Remember School Integration in West Virginia,” paper presented at Piecing It All Together: Ethnicity and Gender in Appalachia, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia, March 3-5, 2000, page 4. (A&M 4206, Box 11, Folder 2).

Note:

Special thanks to Library and Information Science Intern Grace Musgrave for her research assistance.