How to Tell the Age of a Book

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.May 11th, 2020

Blog post by Jessica Kambara, LTAII/Rare Book Room assistant, WVRHC.

Historical events are not only recorded in the content of books. All parts of a book contain information, from the cover design to the paper to the damage sustained over time. Book characteristics vary widely depending on the region and time period they were produced; things like war, national affluence, religious movements, and literacy rates all affect book making. Bibliography or bibliology is the study of books and a wide field of study, as such, it cannot be mastered in one day. However, this guide will break down some simple ways to tell the age of a book and serve as a basic introduction to the history of books.

Question One: What kind of spine does it have?

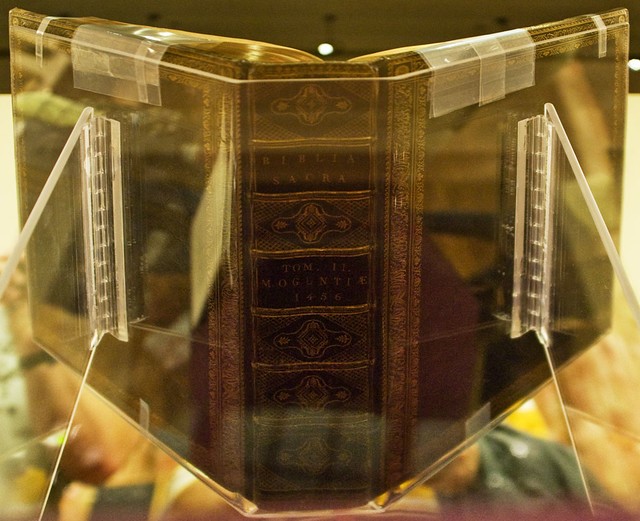

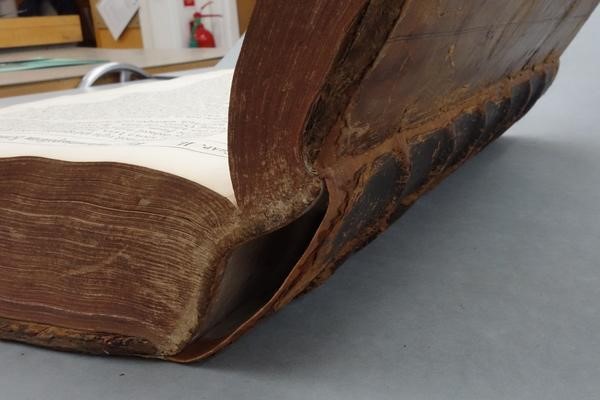

Right off the bat it is easy to identify a modern book; it won’t have the archaic heaviness or brittle wear and tear of books that are hundreds of years old. However, if you come across a book spine that is clearly a few centuries old, look to see if its spine is flat or curved. If it has a stiff and flat spine, it was likely made prior to the 1500s. If it has a rounded spine, it was made during or after the 1500s. Flat spine books were ideal for laying a book open and flat on a table, such as a priest would do when delivering a sermon. Today, the flat spine has re-emerged as a popular spine trend as flexible glues and the sewing machine vastly improved binding strength and flexibility. However, in the past flat spines did a poor job of displacing spinal stress that could cause the binding to break down. Bookbinders thus abandoned the flat spine in favor of a rounded spine that was more flexible and displaced the stress of everyday use better.

The image featured is of a Gutenberg Bible. These bibles were amongst the first major books to be mass produced using the Gutenberg press, today only about 20 fully intact bibles exist.

Unfortunately, the delicacy of flat spines meant they were damaged easily. Many early books were re-backed by conservationists, meaning the original spine was removed and replaced.

Question Two: What kind of binding does it have?

Binding styles vary greatly depending on the region and time. Starting in the 1770s, Hollow Back, a binding style that separated the spine of the text block and the spine of the cover, emerged as the dominant French binding style. However, the hollow back was only sparsely used in other countries like Britain and Holland—until the 1820s.

Up until the nineteenth century, the tight back binding, in which the binding was attached to the spine, was the main binding used in England. After the 1820s, the tight back was rarely used as England adopted the hollow back from the French.

Question Three: Hardcover, paperback, or limp binding?

If you have a standard paperback (generally 6” x 9”), it was likely produced after 1935. The modern paperback was introduced in 1935 by Penguin Books and many agree that the first mass-marketed modern paperback was The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck. The success of the twentieth century paperback can be attributed to the negative economic impact of World War I and the Great Depression creating a demand for cheap entertainment. However, paperbacks did exist before the twentieth century. The English “Penny Dreadful” (so called because they cost one penny) were first published in the 1930’s, a mere five years earlier than the Penguin paperback. Meanwhile, “Dime Novels”, an older American cousin of the Penny Dreadful, were amazingly popular during the American Civil War and date back to the 1860’s. However, as the names suggest, these paperbacks were dirt cheap—costing only about a penny and a dime. As such, they were designed for quick consumption, not durability, and could only loosely be called paperbacks books as they were closer to serials. As with the Civil War, World War II again created a demand for cheap escapism entertainment and paperbacks had another surge of popularity in America and especially with soldiers. This led to the unique creation of Armed Service Editions or ASEs. These paperback books were condensed pocket books designed to be carried around on the battlefield.

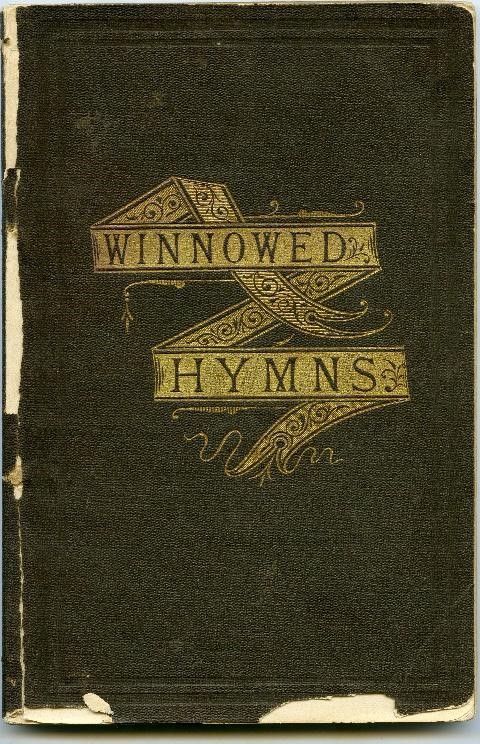

The terms softbacks and paperbacks can be used interchangeably, and can describe books bound with paper and also books bound with cloth (such as Penguin’s early paperbacks). However, there is a third lesser known binding called limp binding. This binding is made from flexible materials like cloth, leather, vellum, and even paper. They can be easy to confuse with paperbacks, but are generally sturdier and designed to last longer. These books are less popular now but are ageless, going back as far as books have been made. The example shown is an American hymn book from the Second Great Enlightenment.

Macfarlan, D. T. McCabe, C. C. Winnowed Hymns. Biglow & Main: New York, 1873. Nelson & Phillips: New York, 1873

Image source: West Virginia and Regional History Center

Hardcover books are a field of study all to themselves. Dating books based on cover designs can be a bit tricky because trends have a habit of re-surfacing, being adopted by other countries at other times, and can also depend entirely on the binder or publishers’ abilities and budget. For example, medieval style books are not limited to the medieval period as the style briefly re-surfaced as a chic (and expensive) trend in the nineteenth century. One easy indicator to look for is color.

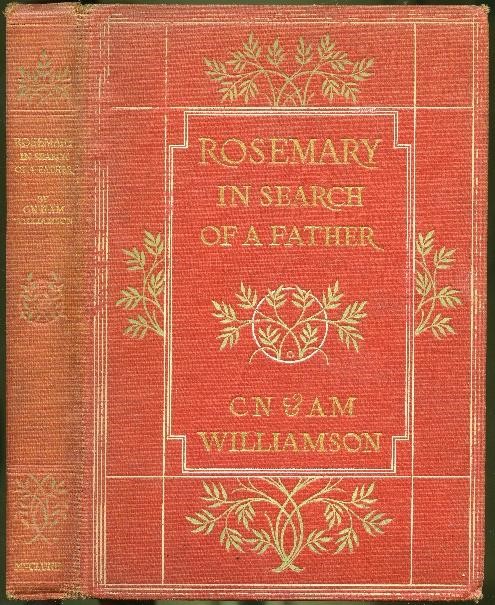

Color is a big indicator of time and generally applies to eighteenth and nineteenth century books. Calf bound books of all shades of brown dominated book covers the majority of book binding history. Ornate decorations and techniques, such as half binding, provided variety, but a huge shift in color occurred with the introduction of Morocco and cloth binding. Morocco binding, named after the Moroccan goats it was originally made from, first appeared in Europe in the early sixteenth century. Goat skin binding was uniquely able to absorb dyes better than any other leather, and can be vibrantly dyed a multitude of colors. However, likely due to the difficulty of getting the material, Morocco binding was not commonly used for English books until the eighteenth century. The publisher William Pickering introduced books bound in publisher’s cloth roughly around 1821 to 1825. Cloth binding was comparatively cheaper than its leather counterparts and much easier to dye, and so color rapidly became a mainstay of book covers.

Williamson, Muriel, Alice. Williamson, Norris, Charles. Rosemary In Search of a Father. McClure, Phillips & Co: New York, 1906.

Image source: West Virginia and Regional History Center

Question Four: What does the cover look like, and is there a dust jacket?

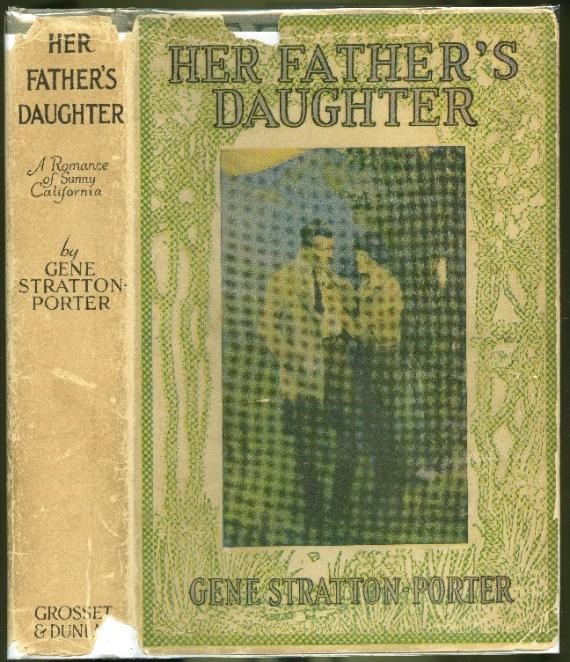

It is entirely possible that a book has lost its dust jacket; however, if a book has its original jacket then it was likely produced after 1857. Books were certainly covered before 1857; however, these coverings were more like wrappings and were all-encompassing and sealed. The flap-style dust jacked widely utilized today was not used until 1857 in England, and the style was adopted by Americans in 1865.

Stratton-Porter, Gene. Her Father’s Daughter. New York: Grosset and Dunlap. 1921.

Image Source: West Virginia and Regional History Center

From illuminated manuscripts to paperbacks, the rich history of books is preserved and on full display at the West Virginia and Regional History Rare Book Room.

Sources:

Corlett, Oliver. A Short History of Paperbacks. IOAB Standard. https://www.ioba.org/standard/2001/12/a-short-history-of-paperbacks/

Leather Binding: Terminology and Techniques. Biblio.com. https://www.biblio.com/book-collecting/care-preservation/leather-binding-terminology-and-techniques/

Romney, Rebecca. The Secret Language of Rare Books: Morocco. Bauman Rare Books: March 10th, 2015. https://www.baumanrarebooks.com/blog/the-secret-language-of-rare-books-morocco/

Vlahos, Jackie. The Ultimate Guide to Types of Book Binding. Printi: October 31st, 2018. https://www.printi.com/blog/ultimate-guide-to-types-of-book-binding/

The Earliest Publisher’s Cloth Binding, Issued by William Pickering. Jeremy Norman & Co.http://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?id=1732

A Short History of Book Covers. Graphene: June 29, 2017. https://www.grapheine.com/en/history-of-graphic-design/history-of-book-covers-1

Shevlin, Eleanor F. The History of the Book in the West: 1700-1800. Volume III. Routledge, 2017.

Masters, Kristen. A Quick History of Book Binding. https://blog.bookstellyouwhy.com/bid/230074/a-quick-history-of-book-binding

Hayes, Lee. Glueing the Spine, Rounding and Backing. The University of Adelaide, May 2018. https://www.adelaide.edu.au/library/special/exhibitions/cover-to-cover/gluing-rounding-backing/