Learning to Read a Book: An Account of a Rare Book Room Assistantship

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.August 3rd, 2020

Blog post by Jessica Kambara, LTAII/Rare Book Room assistant, WVRHC.

During my sophomore year of college, I attended a class led by the curator of WVU’s rare book room, Stewart Plein, on Shakespeare’s Folios. Upon entering the rare book room, I thought I’d like to work there. The Rare Book room had a clean yet cozy atmosphere, and exuded an aura of history and prestige. Halfway through the class, after getting to leaf through the large folio pages of a book hundreds of years old, I was sure I wanted to work there. By the end, I had gotten a job. All it took was asking if there were any work opportunities available, and Stewart set me up with a capstone project and took me under her wing as her assistant.

The first position I ever took in the Rare Book room was effectively that of an intern; however, I was working for course credit and so had to treat it like a capstone project. My objectives were to educate myself on Rare Book room handling and terminology; to compile a portfolio of my inventory work; to create a display; and to present what I had learned. The work itself was quite straightforward. I had to sort through boxes of donated books, create an inventory, and do additional research to determine the historical and monetary value of the book. Stewart was there to guide me through the process, and often steered me if I was stumped. My most important task was to determine the value of a book—essentially data analysis.

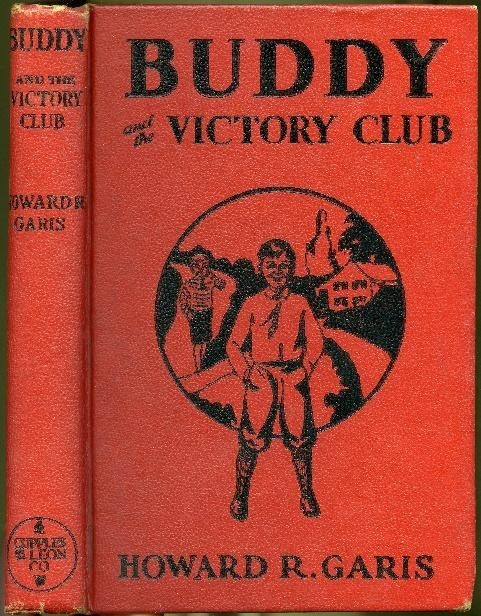

Book value is determined by a number of factors: condition, rarity, edition, age, author, decoration, monetary value, historical significance, and educational potential. Often value was obvious—a rare, highly decorative book by a significant author in good condition was very valuable. However, there were gems within the seemingly insignificant. I took an interest in books produced during war, particularly World War II. I looked for patterns and shifts in patterns. For example, cheaply produced children’s book series are a dime a dozen—sometimes literally—but if you look at the quality and narrative structures you will find cultural shifts. Take the Buddy Series, a string of children’s books that ran for 16 years. For the most part, the majority of the series has little value; however, there is much to be learned from the editions published around World War II. Paper quality dips significantly during the war, an effect of wartime rationing; furthermore, the typical narratives of light-hearted adventures designed to teach good morals shift to tales of can collecting for the war effort and reporting your suspicious neighbor in Buddy and the Victory Club. This gives a better understanding of American wartime mentality, and how it manifested in children’s media. After all, the children taught to report their neighbors by the book, Buddy and the Victory Club, in 1943, were the same ones who grew up to partake in the paranoia of the Cold War and the second Red Scare.

Image source: West Virginia and Regional History Center

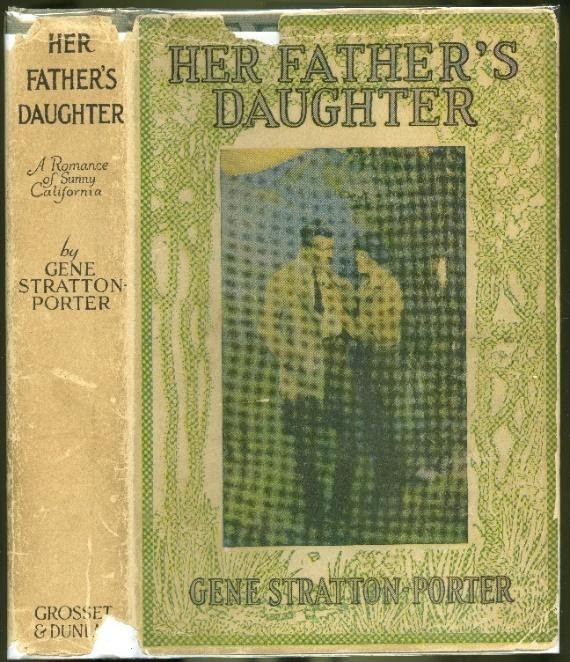

A book’s value can be found not only in its content and material, but also in how it recontextualizes historical periods. You can deduce a lot from what was the cultural norm by examining popular books. It is important to factor in that authors popular during their time might not have survived the modern day. Take Gene Stratton Porter—an author who still has her following, but is not nearly as recognizable as American authors like Jack London or F. Scott Fitzgerald despite being their peer. There is much to praise Gene Stratton-Porter for; she was a conservation activist, a successful American businesswoman, and a bestselling author. At the same time, there is also much to be learned from the startlingly normalized racism against people of Japanese origins in her book Her Father’s Daughter published in 1921. The casualness of how Stratton-Porter’s characters, who are meant to be likable and relatable, discriminate against Japanese people is completely normal. To many, the Japanese Concentration camps of 1942-1946, seem like an unbelievable failure of American morality. However, when contextualized with the reading material that the previous generation grew up with, the camps seem more like an inevitable product of long-standing xenophobia (in addition to being an unbelievable failure of American morality).

Image Source: West Virginia and Regional History Center

Often, historical importance can be found not just in narrative content or material—sometimes it can be in the publishers’ catalogue, which are often found at the end of the story at the back of the book. An otherwise insignificant book can tell you a lot if it also includes the publishers’ catalogue of available books. Compile enough book catalogues, and you can track shifts in advertisements that reflect cultural changes. For example, prior to World War I and II, book catalogues advertised children books as a gender-neutral category—both boys and girls could enjoy books such as The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland. However, as war took over media, book advertisements split into boy books and girl books. Book about war were in high demand, but seen as too violent for girls, and so they were specifically advertised to boys. True to Newton’s third law, girl books went in an opposite direction and focused on things like light-hearted countryside adventures.

By the end of my semester capstone, I had compiled a detailed twenty-page portfolio of my key finds. After learning to read books in a new way and finalizing my portfolio, I then had to transform that information into a real-world tool for education. This is commonly done via displays. As part of my capstone, I set up a library exhibit on war influenced books which was displayed in the WVU library. For my final capstone requirement, I gave a public presentation on what I had learned and the significance of my project and wrote a paper on my overall work.

After I had completed my course credit, I continued to work for Stewart into my junior year as a work-study student. My tasks shifted from an educational approach to a work approach, and in a way was much more simplified while also more complicated. I was no longer expected to produce a gradable project, but I also had to do more diverse work.

My first assignment taught me the importance of organization and job creation—as poor organization had created a summer job for me. A series of unfortunate developments had left important microfilms mixed in a sea of hundreds of other microfilms (please note, this organizational job was not done by WVU staff, but by an outside source). This was the first and last time I worked with the WVU depository—or the depo. The depo is a storage site. It has a small office, and a large warehouse with a towering celling filled with high shelves full of boxes; the highest of which required an aerial platform to reach. It was similar to what you might expect in a factory warehouse, only with better temperature and humidity control. With the aid of depository staff to assist me with heavy lifting, I sorted through dozens and dozens of heavy boxes of newspaper film. Although tedious, there are lessons in blunders and this work certainty taught me the importance of organization, being conscientious of how your work can impact others, and instilled a greater appreciation for the behind the scenes work of acquiring research material.

After that assignment, my work took a return to form as I came back to the Rare Book room to compile inventories of collections—including my largest inventory of 311 Lewis and Clark related items. I also took on the occasional bit of side work, like boxing books or applying clear Brodart book cover sleeves, used to preserve dust jackets, or scanning book covers.

My next big project would be creating a Shakespeare Inventory of Rare Book room books and cross-referencing my inventory against the WVU library database to oversee updates and check for errors. Over the years, WVU’s Rare Book room has compiled one of the most impressive collections of Shakespeare’s work and related content, including an incredibly rare set of Shakespeare’s folios. The time had come when Stewart needed this impressive collection to be inventoried and I set about it.

Each item added to the Rare Book room was naturally recorded in the WVU Library catalog database; however, shifting books and understandable cataloging mistakes can cause discrepancies. And so, to make sure our database was accurate and up to date, I began to cross-reference all the physical copies of the Shakespeare books in the Rare Book room against all the Shakespeare books in the database. At times, locating books was like being on an Easter egg hunt as things like size and value could result in atypical shelving. When I was near the end of my inventorying, I experienced a valuable but painful lesson in backing up information. A mishap resulted in my inventory being deleted and I had to restart. In the end, I created a thirty-page inventory with 183 items.

For a nice change of pace, I also got to work with art and ventured into the libraries central storage area to make an inventory of a collection of donated artworks.

In the midst of working on another large inventory, I had to stop due to the minor issue of graduation, no longer qualifying as a work-study student. That is where I thought my work with WVU and Stewart would end, when I was again called upon to tackle another collection. This time I was hired as a temporary librarian assistant and tasked with organizing a vulnerable collection.

Many issues can be the unfortunate bane of a bookkeeper’s existence. Books are more sensitive than people think, and if humidity and temperature cannot be properly regulated, books may suffer, making them vulnerable to a variety of issues that can cause deterioration such as increased brittleness, mold, and insects, that can invade and spread rapidly between tightly wedged books. Certain precautions, such as masks and gloves, are a must as exposure can lead you to developing a lower tolerance to these issues in addition to other ailments.

In this case, a recently donated collection had problems. Some books were still good, and some were not. Book material is a big factor. I was working with older cloth bound books and leather—paperbacks and a lot of newer books were unaffected. I quickly went about organizing the collection, relocating fragile books to separate shelves and sorting them according to their level of vulnerability.

Unfortunately, another type of bio-hazardous spread impacted my work halfway through sorting. Covid-19 resulted in WVU closing the libraries, and with that I began a life of remote work.

Remote work was a strange change of pace from my hands-on work. I could not inventory what I could not see, and so I took the opportunity to educate myself on book history, book care, and other topics that had long interested me. I edited audio files, wrote blog posts, and did beta work for Stewart. Now, at the close of my temp assignment, I’m completing my final task—writing a reflection.

I’m very grateful to all the WVU library staff who aided me in my work, and especially grateful to Stewart Plein for providing me with the opportunity to return again and again.