The Voting Rights Act Turns 55

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.August 6th, 2020

By Danielle Emerling, WVRHC

Fifty-five years ago today, on August 6, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, meant to remove racial discrimination in voting. The Act was a landmark for the civil rights movement. However, its passage was met with debate, and its legacy continues to be challenged. The Act’s path through Congress is the topic of an online exhibition from the WVRHC archives, For the Dignity of Man and the Destiny of Democracy: The Voting Rights Act of 1965.

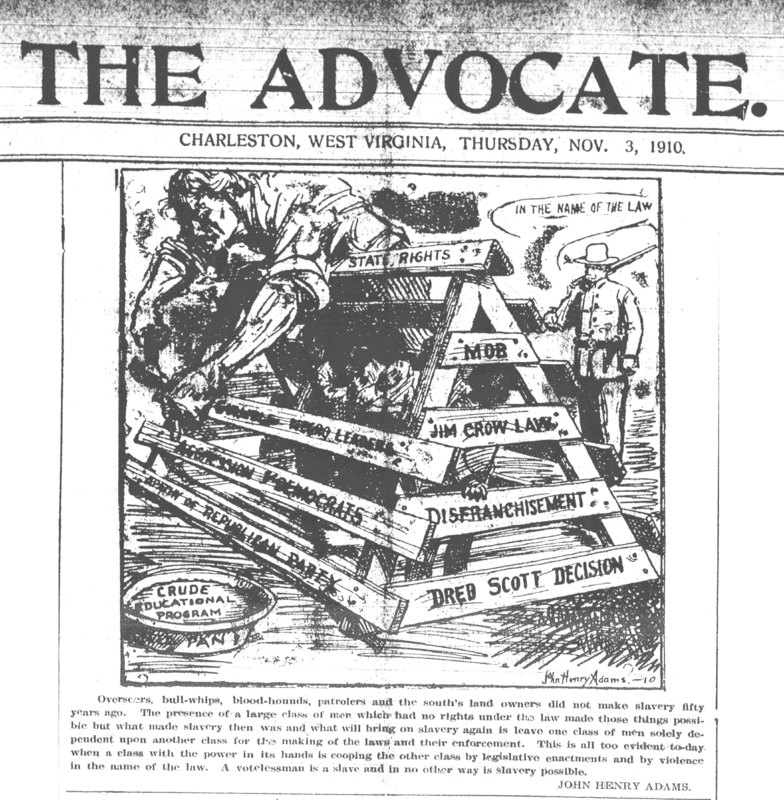

The Voting Rights Act is rooted in the Fifteenth Constitutional Amendment. Enacted in 1870, it established that the right to vote could not be denied on the basis of race. Yet African Americans, particularly those residing in southern states, continued to face significant obstacles to voting. These included bureaucratic restrictions, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, as well as intimidation and physical violence.

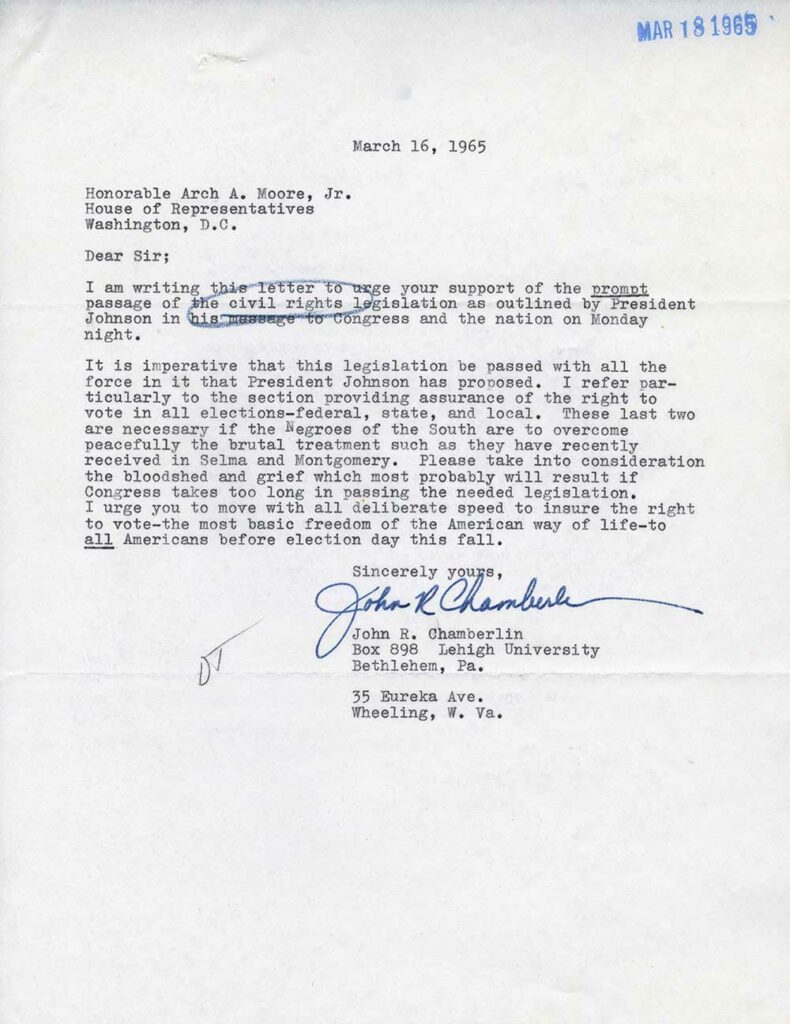

Little was done at the federal level to enforce Reconstruction Era laws, including the Fifteenth Amendment, until the mid-twentieth century. Even after the passage of civil rights bills, however, discriminatory practices depressed voter registration rates for African Americans living in the South. When civil rights activists, including recently deceased Congressman John Lewis, organized a voting rights campaign in Alabama in 1965, it culminated in violence on March 7 when Alabama state police brutally attacked peaceful marchers in Selma. The event galvanized an outpouring of support for a bill protecting the right to vote for all Americans.

The President addressed a joint session of Congress on March 15, 1965, calling on them to pass a voting rights bill. He opened his speech explaining that he spoke “for the dignity of man and the destiny of democracy.”

The Administration sent a proposed bill to Congress two days later, and though it had strong bipartisan support, Congress spent several months debating various aspects of the legislation. Traditionally, most powers to register voters and protect the right to vote have fallen to state and local governments. Congress needed to decide whether the Federal Government should shift this balance of power. Members spent several months debating various aspects of the legislation, including poll taxes and automatic triggers. Though they were banned in federal elections, many states levied poll taxes as a prerequisite to voter registration. Another aspect of the bill automatically “triggered” certain actions, such as outlawing literacy tests and requiring states or counties where discriminatory practices were in place to seek federal “preclearance” before establishing new voting laws.

In the Senate, a 24-day filibuster of the bill ensued. Southern senators believed the bill was unconstitutional and punitive to the South. Democrats and Republicans signed a petition for a cloture motion, and four days later, the Senate approved debate-limiting cloture, ending the filibuster. This was only the second time in its history, and the second time in two years, that the Senate had stopped debate in order to vote on a civil rights bill.

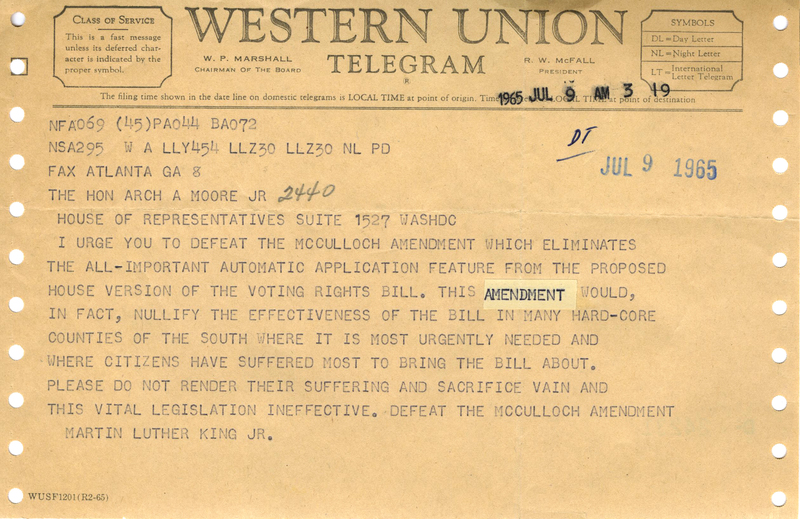

In the House, Republicans proposed a substitute bill, known as the Ford-McCulloch bill, which removed the automatic triggers. Civil rights leaders expressed strong opposition to the Ford-McCulloch bill. On July 9, 1965, the House rejected the substitute bill and passed one with automatic triggers and a ban on poll taxes in state and local elections.

After a conference committee resolved the differences, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law, finally fulfilling the promise of the Fifteenth Amendment. It was tremendously successful. The disparity between white and black voting registration rates dropped from nearly 30 percentage points in the early 1960s to just 8 percentage points a decade later.

Congress has reauthorized the Act multiple times, most recently in 2006. In 2013, however, the Supreme Court overturned a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. In Shelby County v. Holder, the Court invalidated the “coverage formula,” which determined the states and localities required to seek preclearance for changes in voting rules that could affect minorities. Following the ruling, several states began implementing photo ID laws.

For the Dignity of Man and the Destiny of Democracy: The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a digital version of an exhibit that was on display in the WVU Downtown Campus Library’s Rockefeller Gallery. Materials in the exhibit come from the Arch A. Moore Jr. congressional papers, WVRHC; the WVRHC newspaper collection; and the Center for Legislative Archives, NARA, featured in the Association of Centers for the Study of Congress’ The Great Society Congress exhibit.