An Undergraduate’s Take on Race, Justice, and Social Change Through Cookbooks

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.February 22nd, 2021

Blog post by Christina White, undergraduate researcher at WVU

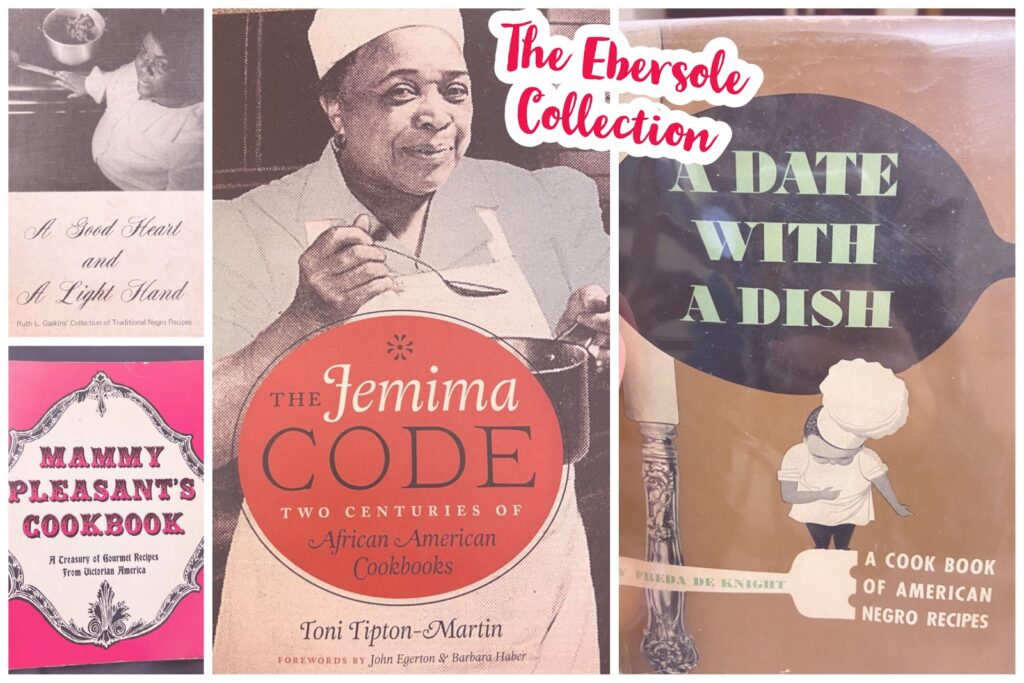

This series of blog posts will feature the following books: Mammy Pleasant’s Cookbook, A Date with a Dish, A Good Heart and a Light Hand, and The Jemima Code

Note: The cookbooks in this series feature revolutionary and talented women of their times. Reading their stories in the West Virginia & Regional History Center, I chose to refer to the authors by their first names. Their casual tones conveyed a desire to connect with the reader, and being one of those readers, I wanted to uphold that connection while maintaining the highest respect for the work they created.

I found a place on campus I never knew existed. The West Virginia & Regional History Center houses doorways into the past, into the day-to-day struggles, relationships, and moments of sweet relief. I’m sifting through the realities of women, Black Americans, and other marginalized groups to elucidate forces that affected their lives. These forces, far from obsolete, persist into today’s social landscape, whether it is in private conversations at the Mountainlair or national media coverage.

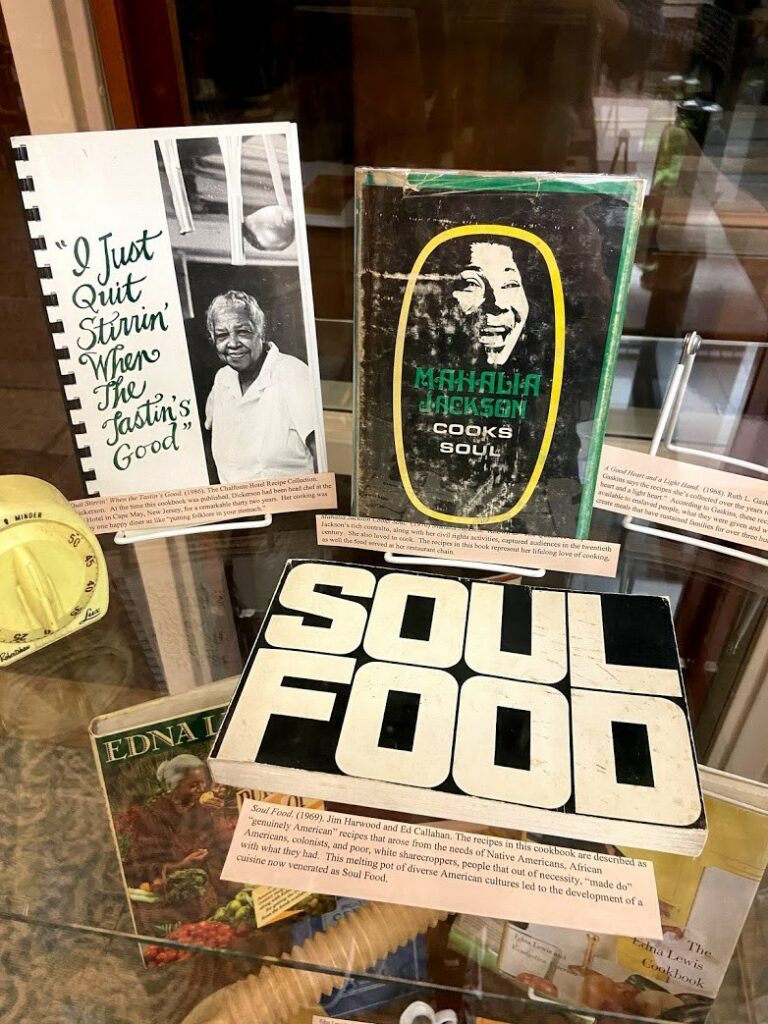

Donated by the late Lucinda Ebersole, an acclaimed writer and cookbook collector, hundreds of cookbooks await analysis on the sixth floor of the Downtown Library. I started with Mammy Pleasant’s Cookbook, which captures the travels and fierce entrepreneurship of Mary Ellen Pleasant.

I realized that recipes cast a new light on history with an intimate truthfulness. Standard high-school history books don’t reveal the ins and outs of stewing a turtle, running a renowned kitchen on a senator’s riverboat, or feeding enslaved people at secret boarding houses of the Underground Railroad. The language around recipes, be it an author’s note or long introduction, tells a story about a time period. How are specific groups of people described? Mammy Pleasant’s Cookbook uses “Negro,” while later books opt for “African American” or “Black.” Who knew a timeline of societal awakenings and changes in norms is etched between the dinner and dessert section of a cookbook?

As I flipped the page of a hundred-year-old cookbook, a plume of dust shot into the air. I caught a whiff of an unfamiliar scent that reminded me of my grandmother’s stack of outdated newspapers, musty yet potent. I felt like a foreigner in an unexplored country, getting to know the smells and rituals of a group whose history was scrubbed and sanitized by dominant groups.

For example, the “mammy” stereotype — a jolly, rotund Black woman who cares for everyone and whips up a southern feast — seemed awful but extinct in today’s world. However, it was only three months ago that the international brand Quaker Oats removed a notorious mammy stereotype from their most famous product line, Aunt Jemima syrup and pancake mix.

Check out this TikTok on “How to Make a Non Racist Breakfast.” The creator spells out how a pancake icon propagated racism: https://twitter.com/singkirbysing/status/1273053553876074496

The content of these frayed cookbooks is so pertinent to the current moment. Their lessons on racial identity and inclusion matter in policy decisions, university trainings, and dorm-room discussions among friends.

My goal in these blogs is to share stories from sources as raw, as delicious, and as unfiltered as personal recipes. I don’t mind if opinions are unsettled or comfortability is shaken. I’ll also let you in on experiences that I’ll likely never witness, like skinning an opossum or preparing fruit punch for a hundred people at a church social.

At some points, I found myself agitated over a cookbook. I texted friends and annoyed my family about what I read, mostly injustices against the authors and their communities. Civil rights, intercultural blending, mental health, women’s suffrage, gender issues, slavery, single parenthood, poverty, environmentalism, and more fills the pages of the Ebersole Collection. This blog would be lucky to dust off just one of those topics!

I invite you to accompany me into the daily lives of skilled chefs who objected in the most cunning, illusive way. Their judgements and hopes are woven into the blank spaces between recipes for roast duck and spice cake.

I’m excited to show you what I uncovered after hours in the West Virginia & Regional History Center, carefully leafing through these antique cookbooks on a special book pillow.

I’m a senior pursuing a double major in Biology and International Studies and intern at the WVU Center for Resilient Communities. Welcome to my excursion into the Ebersole Collection!

*I will capitalize the term “Black” in agreement with the New York Times’ 2020 decision to respect a shared cultural identity. Read more about their decision here.

Members of the WVU community can make an appointment to browse and read books from the Ebersole Collection by visiting: https://wvulib.wufoo.com/forms/modzhm01sagr2x/

A warm thank you to our dedicated Rare Book Librarian, Stewart Plein, and our Reference Supervisor, Jessica Eichlin, for empowering me during this process. Without their work, organizing the hundreds of books and spreading the word about their content would not happen.

More about the Ebersole Collection: https://news.lib.wvu.edu/2018/12/05/the-importance-of-a-good-cookbook/

Written by Christina White

Biology and International Studies

cdw0030@mix.wvu.edu

*photos taken by Christina White