Three Powerful West Virginia Black Women: Their Work Revealed In Ancella Bickley’s Collection

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.January 19th, 2021

Blog post by Linda Blake, University Librarian Emerita

Dr. Ancella Bickley’s extensive collection of her research materials and writings in the West Virginia and Regional History Center reflects her research on a wide range of topics pertaining to the Black experience in America and particularly the West Virginia Black experience. Bickley, an educator, historian, and writer, was especially interested in revealing the unique contributions of Black women. While the transcripts of her oral history interviews with Black teachers who experienced the integration of schools reveals the major contributions of many Black West Virginia women, I have chosen three other noteworthy women to introduce here.

The amount of information about each of these women varies widely. Dr. Bickley collected enough information to write an entire book about the first woman, Memphis Tennessee Garrison. She found a little less about the second woman, Bessie Woodson Yancey who was recognized by scholars for her writing. As for the third woman, Mollie Gabe, she largely remains hidden in history except for the research and recognition by Ancella Bickley.

Memphis Tennessee Garrison

1890-1988

Dr. Bickley’s book, written with Lynda Ann Ewen, Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the Remarkable Story of a Black Appalachian Woman narrates the life of a woman of accomplishment during the heyday of mining in West Virginia and the Jim Crow era of the 1920s through the 1940s. Memphis Tennessee Garrison was a community activist, coal company mediator, and educator. One of her most impactful activities was to spearhead the NAACP Christmas Seals, a fundraising program, as just part of her long commitment to that organization. She used her voice to support the Republican Party and its candidates too by working with the Party’s women’s organization. She developed cultural and recreational opportunities in the mining communities by bringing entertainment to the miners and their families; and was also a liaison with the coal companies and miners to calm labor and racial disputes. As an educator she created techniques for teaching special needs children before the term “special education” was coined.

Memphis Tennessee Garrison was one generation removed from slavery and was a powerful activist for the Blacks of West Virginia and the nation. As the book about her life notes, she “deserves her place in the lists of important women, important black Americans, and important Appalachians.”

Further Reading:

Buchanan, Harriette C. Appalachian Journal, vol. 29, no. 3, 2002, pp. 369–371. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40934867. Accessed 6 Jan. 2021.

Wikipedia contributors. “Memphis Tennessee Garrison.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 19 Dec. 2020. Web. 6 Jan. 2021.

Bessie Woodson Yancey

1882-1958

I am a Negro,

Dusky

As my native jungles,

Subtle

As the creatures that move therein,

Rollicking

Like the noon-day sun.

Suffered all,

Yet I bring goodwill,

Turning loss to gain,

Wrestling joy from pain,

Changing tears into laughter!

Bessie Woodson Yancey penned the poem above, and many more, for her book Echoes from the Hills which was published by her brother, Carter G. Woodson, the famed Black historian and activist. Katharine Rodier wrote of Yancey’s book “her poetry signifies a self-determining moment in the history of African American writing.” In the poem, Yancey demonstrates her deep pride in her race. In addition to her race figuring in her poetry, Yancey was also influenced by her Appalachian identity. Here she demonstrates her deep pride in her state.

If you live in West Virginia,

Come with me and pause a while.

See her wealth and power rising,

See her plains and valleys smile!

Aside from her poetry Yancey wrote more than one hundred pieces, mostly editorials, for Huntington’s Herald-Advertiser, 1946-1956. Her writing demonstrated “evidence of a lively mind engaged in the vital political issues of the day” (Katherine Smith) from the local, national, and international levels. She was particularly vocal regarding West Virginia’s place on the national scene. Her voice also supported the civil rights movement, and she received a death threat from Huntington’s Ku Klux Klan, yet she continued to express her opinion on race up to ten years later. Katherine Smith also said of her “Yancey’s editorial work unsettles assumptions about women’s experiences as African-American Appalachians.”

Bessie Woodson Yancey rose above the strictures placed on Black women in mid-century America to speak her truth regarding world affairs and to offer the world beauty through her poems.

Further reading:

Rodier, Katharine. “Cross-writing, music, and racial identity: Bessie Woodson Yancey’s Echoes from the Hills.” MELUS, vol. 27, no. 2, 2002, p. 49+. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A92589725/LitRC?u=morg77564&sid=LitRC&xid=c5862914. Accessed 6 Jan. 2021.

Smith, Katharine Capshaw. “Bessie Woodson Yancey, African-American Poet and Social Critic.” Appalachian Heritage, vol. 36 no. 3, 2008, p. 73-77. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/aph.0.0060.

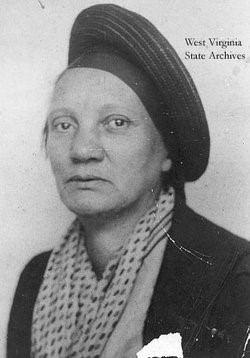

Mollie Gabe (Mary Elizabeth Johnson)

ca. 1853-1957

Mary Elizabeth Johnson was born into slavery in Falls Mills in Braxton County. Mollie Gabe’s mother Jane Rhea was enslaved by Dr. John Rhea who brought Jane and other slaves from Virginia. According to varying accounts Dr. Rhea sold Mollie as a child to a family in Clay County where she worked until the Civil War ended. Although Mollie did not know that the war had ended and she was a free person, her mother did know and sent her brother, Mollie’s uncle, to fetch Mollie back to Falls Mill where she remained the rest of her life. Johnson acquired the nickname Mollie Gabe when she married Alexander “Gabe” Johnson in 1871.

In Falls Mill she developed a reputation for being an energetic hard worker, and a midwife and healer using traditional Appalachian remedies. In Ancella Bickley’s profile of Mollie Gabe, she counts Gabe among the “ordinary people who faced day-to-day challenges in the best way they knew how, serving their families and their communities with honor and earning the high regard of many who knew them.” She traveled from farm to farm washing clothes or helping with butchering. Her husband Gabe (Alexander) was also an itinerant laborer. He and his brothers had been slaves of the Braxton County family of William Haymond with whom Mollie and Gabe continued a cordial relationship. They both provided labor for the community and since Gabe owned a team of horses, he delivered groceries, plowed fields, hauled items and worked with his brothers as extra hands as needed.

I doubt that Mollie could read, but she is believed to have traveled to Black colleges and Black high schools to tell her story of being enslaved. It is also said that she walked about a mile at 86 years old to the polls to cast her vote for the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln.

According to the 1910 census, Mary and Alexander Johnson had been married 42 years and had 10 children and she said in an interview that she raised many more. Her gravestone in Falls Mills shows that she lived to be 99 years old, but other accounts show her age at death to be 104.

Further Reading:

Bickley, Ancilla. “Mollie Gabe.” Appalachian Heritage, vol. 19 no. 4, 1991, p. 34-37. Project MUSE, doi:10.1353/aph.1991.0063

Interview with Mollie Gabe. Braxton Democrat, February 2,1939 and reprinted October 29, 1982. http://sites.rootsweb.com/~wvbraxto/mollie.html Accessed January 5, 2021