A Day in the Life of a Digital Archivist: Partying Like It’s 1999

Posted by Admin.February 27th, 2023

Written by Elizabeth James, the Digital Archivist at the West Virginia & Regional History Center.

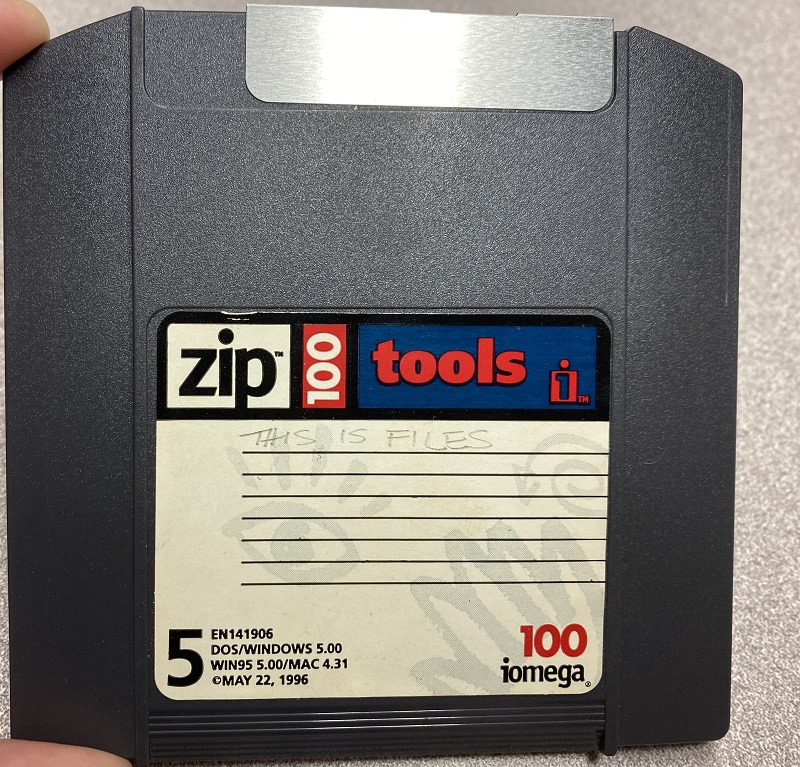

What kind of items come to mind when you think of archives or archival materials? What about digital archives? When it comes to digital archival materials, many people will think about scanned copies of physical materials like books or maybe even web pages saved to a platform like the Internet Archive. But there are many more formats in WVU’s archives: from 3.5 inch floppy disks to Zip disks to CDs, contemporary archives contain all of these material types and more. These media formats contain what are known as born-digital materials, or materials that were originally created digitally.

In this post, I’ll take you through the journey of one seemingly familiar format through the typical procedures used in the WVRHC to remove content from the original media and make born-digital archival materials accessible.

Let’s meet our protagonist for the day: the compact disc, or CD, a format first introduced to the commercial market for music in 1982. Though CDs are still common, when it comes to any media formats you need the following two things in order to access the content:

- Have equipment to read the item—for instance, if you have a 3.5 inch floppy disk, you need a 3.5 inch floppy disk drive.

- Have software to read the files saved on the item—if you have a Word Perfect file from 1992, that file is designed to display correctly using the 1992 Word Perfect program.

For CDs, external USB drives and internal disc drives are still accessible. I have an internal and external disc drive I like to use with CDs and DVDs I’m processing. Since we have the equipment to read the item, let’s get started! This example uses a CD found in the International Association for Identification Collection at the West Virginia & Regional History Center.

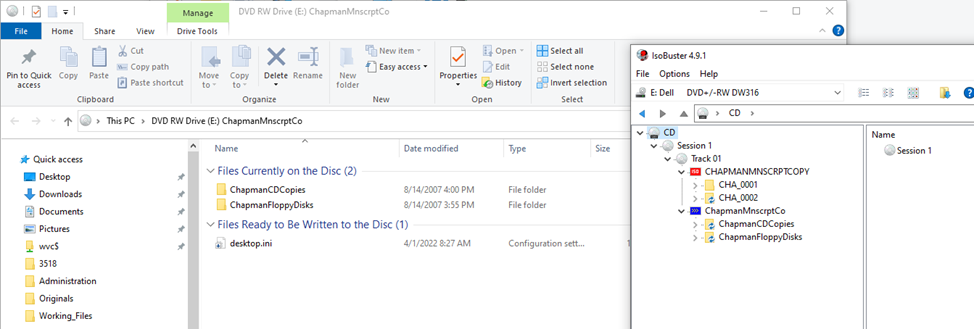

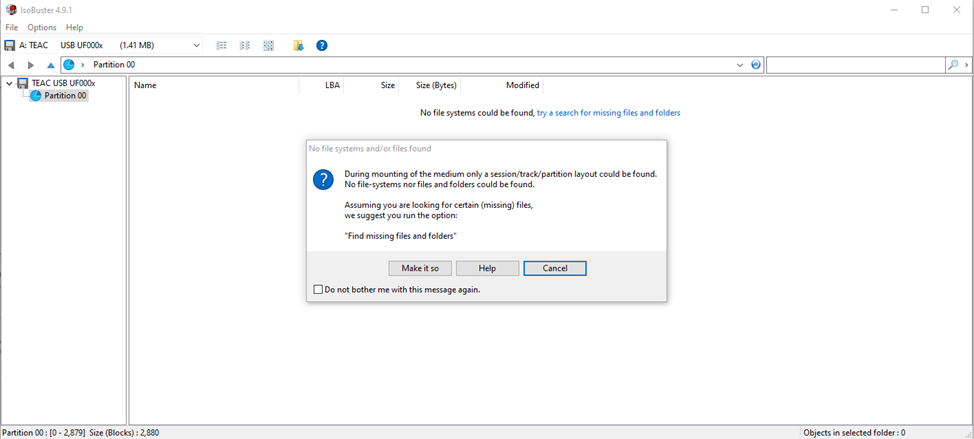

Though I couldn’t tell until I inserted the disc, this CD is a data CD which means that the CD contains non-audio content. To access the files, I need to open the CD on my computer using Windows Explorer rather than having any audio or music files play automatically. On the left you can see the view if you use this approach. However, CDs can have multiple file systems underneath what you see in this basic view. On the right is the view you see when using IsoBuster, a software that supports a more digital forensics style approach to examining files. In this view, you can see multiple file systems that each tell your computer’s operating system how to access the files on the CD. Multiple file systems may contain different files, so we want to make sure we check to see that we grab all of the unique files.

Luckily, these two file systems contain the same files, so we’re safe to use a software like Teracopy that will copy these materials off the CD without modifying any of the files or file metadata, a term archives and libraries use to talk about information that describes the files. After all, we can’t party like it’s 1999 if we unintentionally edit the files and change the “Date Modified” to 2023. By using Teracopy, which retains the original file metadata and ensures that we don’t accidentally edit the file along the way, we can assure researchers that what they’re accessing in the archive is as close to what the original creator saved to the CD as possible.

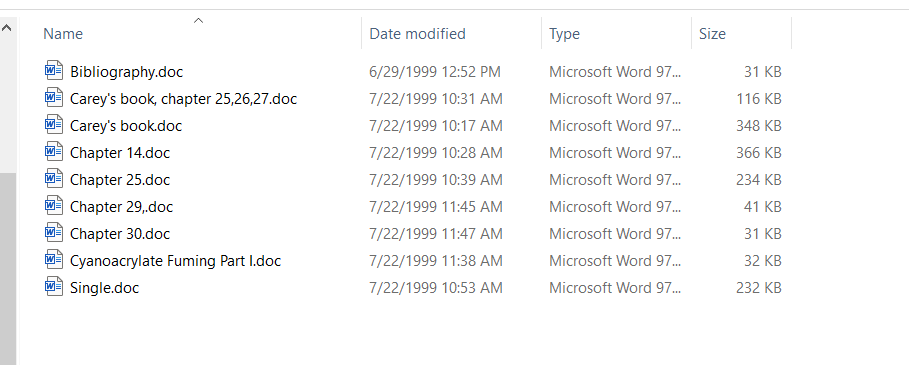

Now we can move on to step two: determining if we have the software to access the files. Upon looking at this content, I discovered the CD was a front for something unexpected: a floppy disk! The files on the CD were a copy of materials found on a floppy disk in the collection. All of the files on the CD are dated to 1999, which is conveniently the title of a catchy Prince song and the inspiration for this article title. We can see that the files are Microsoft Word-based, albeit Word 97, which means that opening the files in a modern version of Word should be fine.

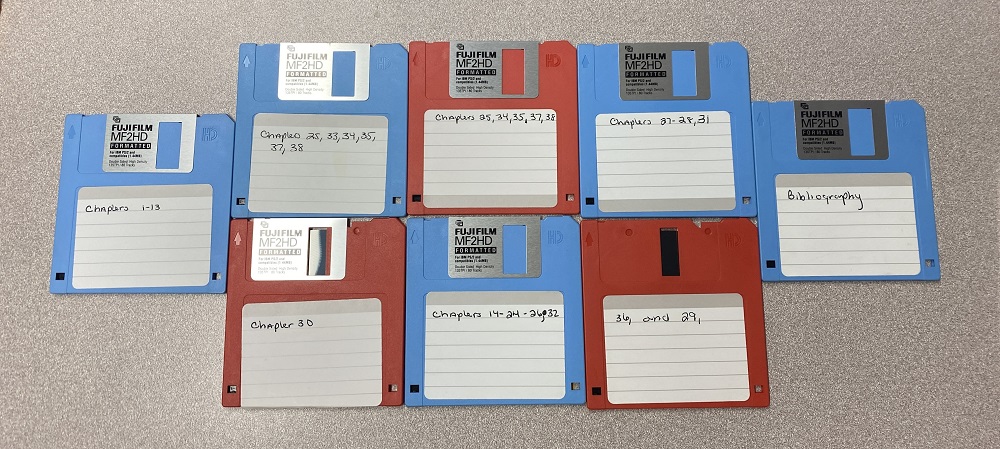

But what’s on the disc? Well, it’s an unpublished history of identification and the International Association of Identification by Carey Chapman. We have several versions of this manuscript across both printed materials and floppy disks, which means that any researcher can examine these versions to gain a sense of what Chapman’s writing process was like. You can see some of the floppy disks where this content came from below. If the number of disks seems like a lot, remember that floppy disks can only hold 1.44MB of information. To give you a sense of scale: a 2GB thumb drive holds 1,422 times as much content as a single floppy disk.

Let’s up the difficulty level and go to :

Time taken: 20~ minutes

If I wanted to conclusively say I had tried every avenue, I would use something like a Kryoflux that reads every available bit, even floppy disks with issues. While I might use this approach in the future, this floppy disk seemingly contains a translation of a document and the content of the disk isn’t vital to understanding the collection.

Getting content off this CD was comparatively easy. For other materials, I’ve had to do everything from emulate MS-DOS to see the contents of a program, trawl the internet for 5.25-inch floppy disk drives, to doing research on what type of computers and operating systems the United States Senate was using in the 1990s. Suffice to say, digital archives work takes many forms. Though the digital materials in this collection are still being processed, you can reach out to Elizabeth James, Digital Archivist, at elizabeth.james1@mail.wvu.edu if you have any questions about accessing this item or anything I’ve written about here.