Mountaineers’ Road to Statehood: Reflections on “Born of Rebellion” with Graduate Assistants Devon and Erica

Posted by Mary Alvarez.November 20th, 2023

This post was written by Devon Lewars and Erica Uzak.

“Born of Rebellion: WV Statehood and the Civil War,” a traveling exhibit established by the West Virginia Humanities Council, has made its way to the Downtown Library’s Rockefeller Gallery. Civil War historians and WVRHC GAs Erica Uszak and Devon Lewars will be sharing their first impressions of the exhibit.

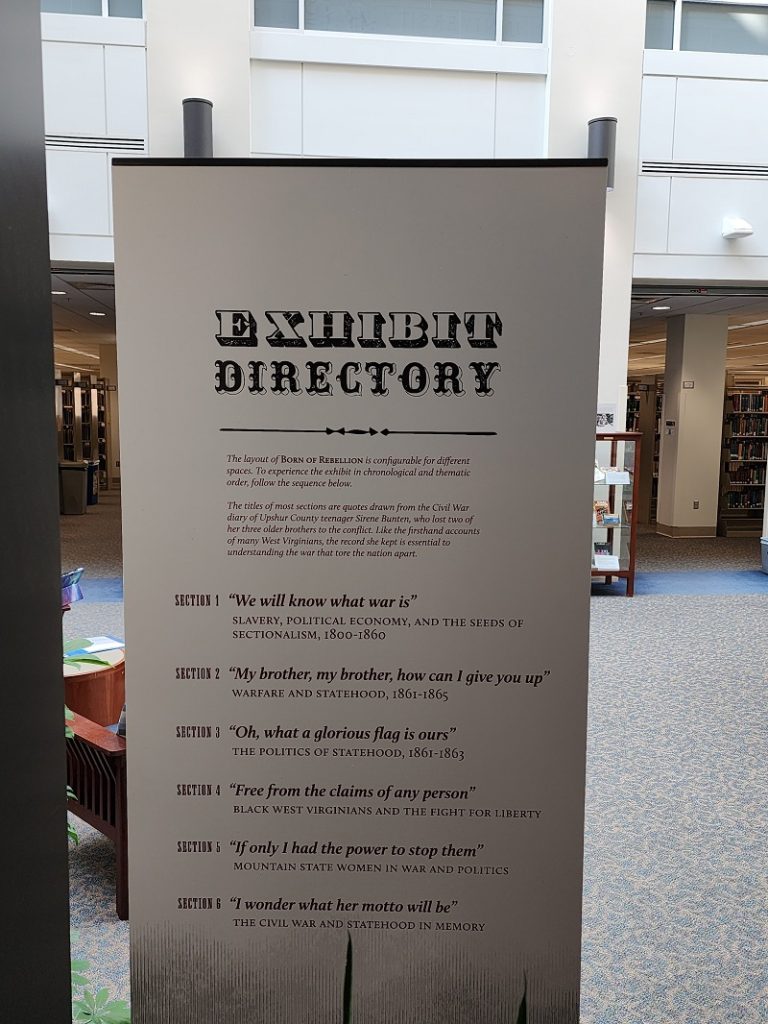

When visiting, take note of the suggested panels to follow. See exhibit directory below.

Each section title is a quote taken from the diary of Sirene Bunton, a teenager at the time, she lost two of her brothers to the conflict.

See Devon’s favorite panel below:

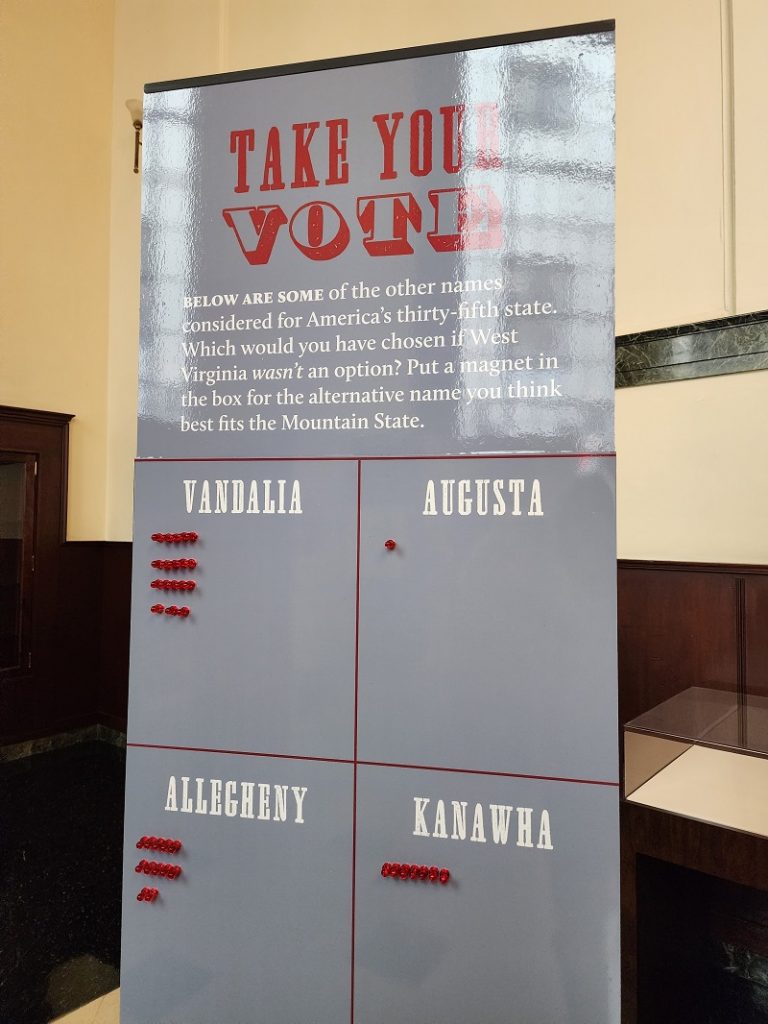

This panel engages visitors by asking them to choose what the state should have been called if “West Virginia” wasn’t an option. Magnets are provided to visualize votes for each alternative name. Stop by the second floor to cast your own!

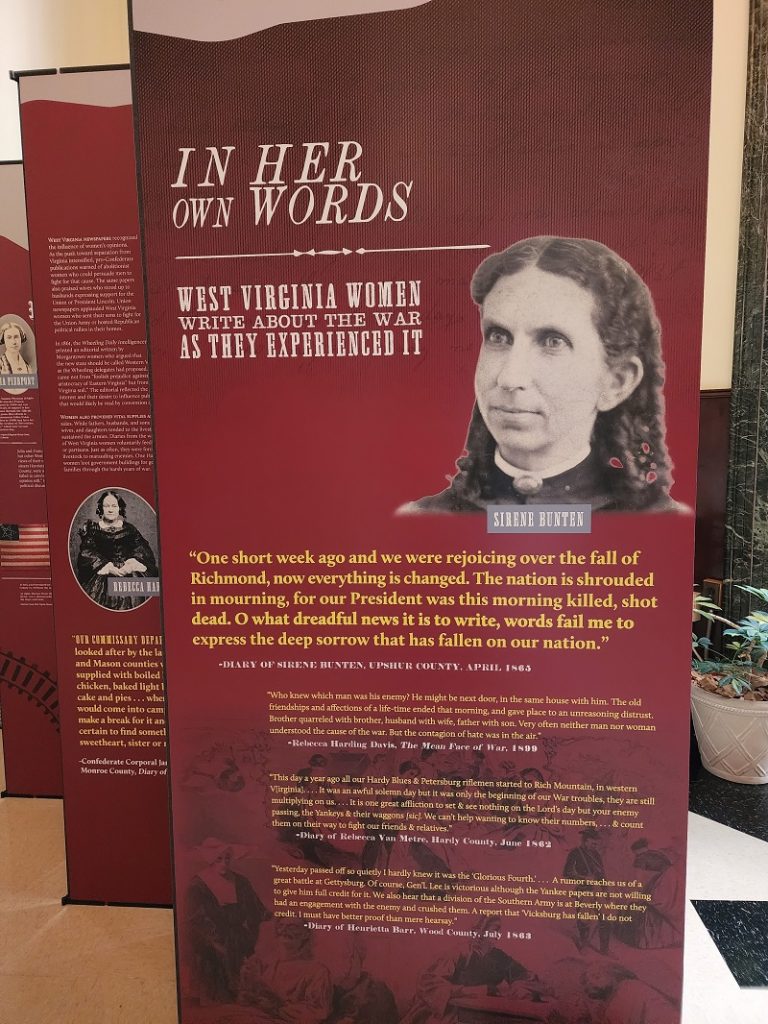

The panels have been designed to showcase different perspectives of the conflict which can be seen by shifting your body to each side of the panel board. See below two different perspectives of the same panel:

“Born of Rebellion” utilizes a variety of sources that highlight the voices of women, African Americans, and Virginians/West Virginians. See for yourself the beautiful details that were put into this exhibit by visiting the downtown library through the first week of December!

The above section was written by Devon Lewars.

President Abraham Lincoln came to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on November 19, 1863, tasked with giving “a few appropriate remarks” in a dedication paying tribute to those U. S. soldiers laid to rest in the Soldiers’ National Cemetery. He began his address by reminding the audience of the nation’s core principles found in the Declaration of Independence, which stated that “all men are created equal.” He concluded his address by pledging “increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion,” and an increased commitment to the soldiers and the ideas found in the Declaration, promising that “these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

A few months earlier, on June 20, West Virginia had been granted statehood into the United States, breaking free from the seceded Confederate state of Virginia. West Virginia’s involvement in the Civil War and its statehood are discussed in the new exhibit, “Born of Rebellion.” This exhibit explores the war’s beginning and the importance of slavery at the heart of the conflict, military action in West Virginia, the political statehood process, Black West Virginians, Union and Confederate West Virginia women, and the commemoration and memory of the war in the state. The exhibit condenses many complicated details and presents the war in an accessible way. It does not shy away from the issue of slavery and discusses the hardships that enslaved people faced in slavery and the continued struggle for freedom after emancipation. One of the most moving aspects of the exhibit are the enlarged photographs of men, women, and children, who look directly at the viewer. Most striking is the photograph of the young children in the Lincoln school in Wheeling, which “was one of the first publicly funded educational institutions for Black children in the state,” according to the exhibit. It adds that these schools did not have the same state funding as all-white schools. Many schools stayed racially segregated until 1954, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that “separate but equal” was “inherently unequal.” One of the panels about Black West Virginians concludes, “In many ways, the fight for equality has been nearly as difficult as the antebellum struggle against slavery,” as they fought against racism, discrimination, and white violence.

While the road to full freedom and equality for all would be treacherous and long, many West Virginians fought for the “new birth of freedom” that Lincoln had promised. They renewed their commitment to independence and freedom in their state motto: Montani Sempre Liberi – Mountaineers are always free.

The above section was written by Erica Uzak.