A New Way of Looking at Thomas Jefferson’s Legal Dictionary

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.December 16th, 2019

By McKayla Herron, Graduate Assistant at the WVRHC

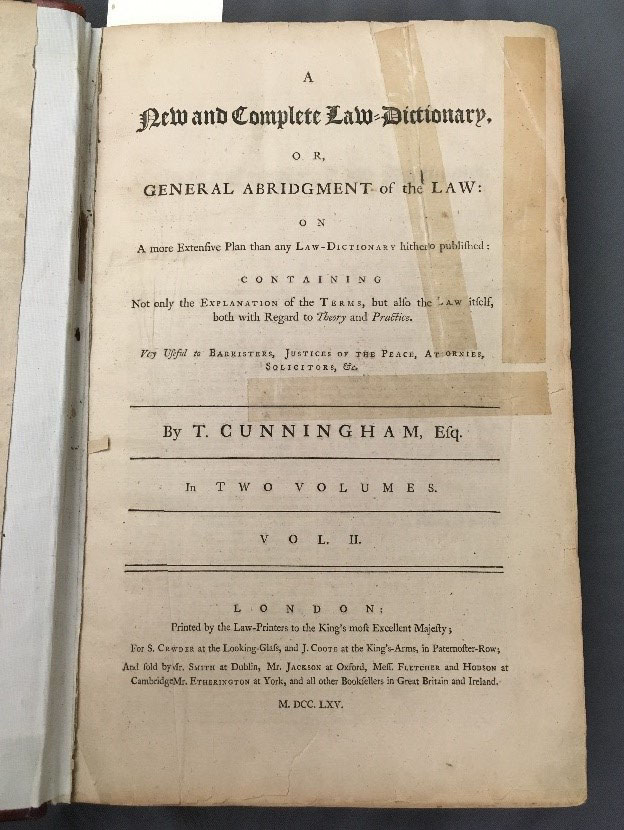

Working as a graduate assistant at the WV&RHC, I have been surrounded by amazing archival materials. This semester I had the opportunity to undertake an in-depth study of Thomas Jefferson’s Common Law Dictionary, one of the many treasures found in our Rare Book Collection, as part of my coursework for ARHS 412: Collections Care and Preservation of Material Objects. (This book was featured in a previous post by Rare Book Librarian Stewart Plein.) Utilizing a microscope to examine the book, I was able to learn more about the materials that comprise it and the techniques used to make it.

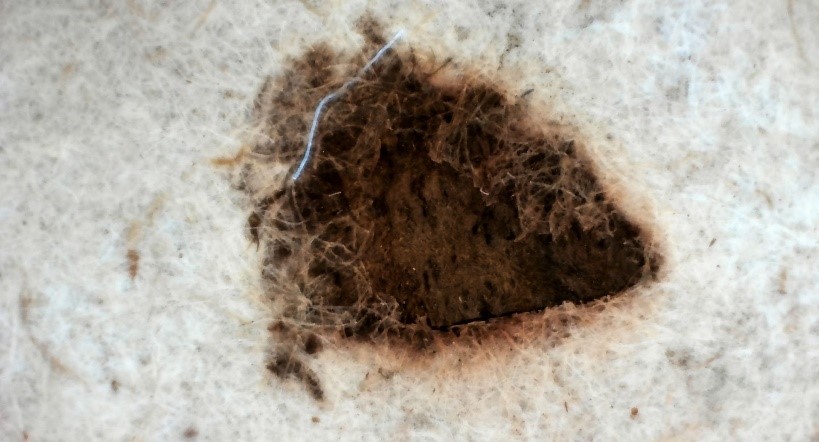

This legal dictionary was printed in London in 1765. Its paper is made of linen and cotton rags, as was common in the eighteenth century. The rags would have been soaked in water, beaten, and broken down into a pulp that the printers then dipped into paper molds. The resulting sheets are both high-quality and durable. The microscopic image below shows the interwoven cotton and linen rag fibers in the dictionary’s paper.

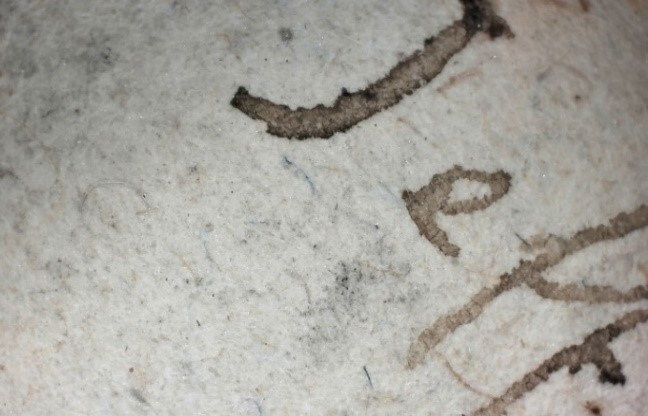

Microscopic analysis revealed that many tiny imperfections are present in the paper. As illustrated in the image below, what appeared to be a small ink smudge to the naked eye is actually some type of foreign material embedded within the rag fibers. The fact that the fibers both surround and cover this material indicates that it was present when the paper was made. The presence of this material is understandable, seeing as the paper was handmade.

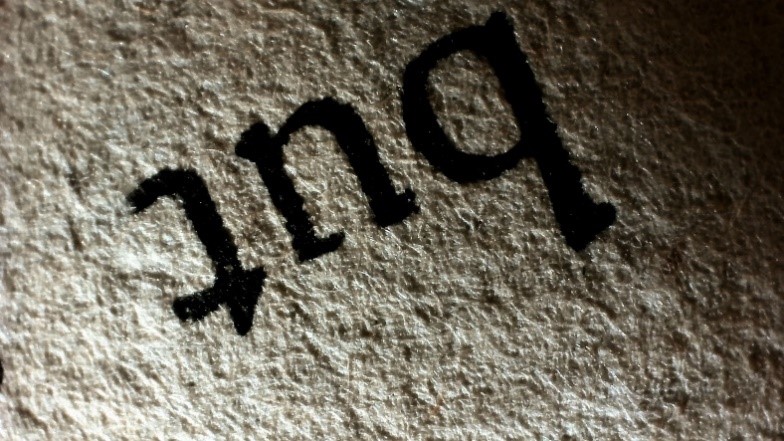

Images taken with the microscope also illustrate the differences between the book’s printed ink and the ink which was hand-applied by Jefferson. The printed ink is much darker and was applied more uniformly. The brown tint in Jefferson’s ink is indicative of iron gall ink (which was the most popular writing ink used in the American colonies). Iron gall ink is known to be extremely acidic and, over time, can eat through the paper it is applied to. There is no evidence of this happening to Jefferson’s dictionaryyet, but we will have to watch carefully to see if it starts to!

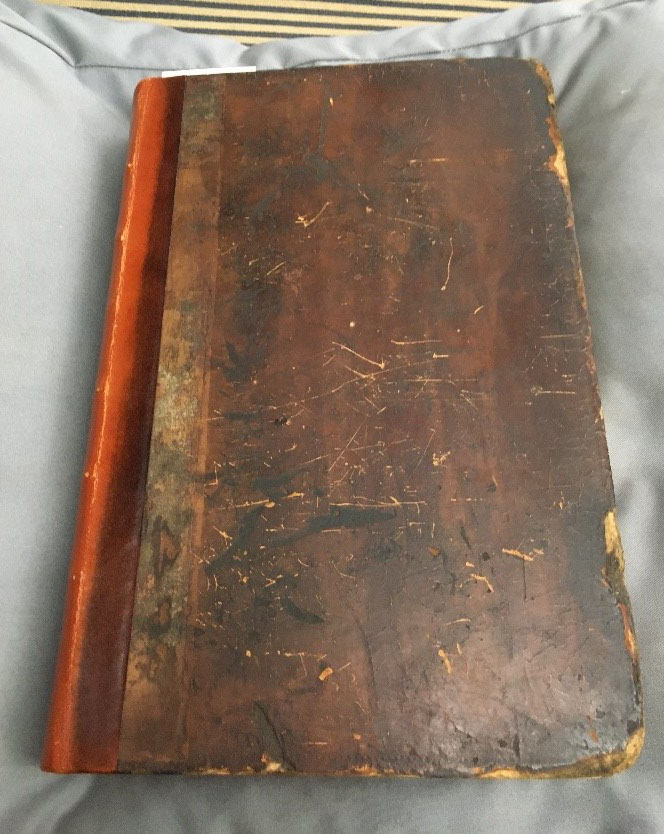

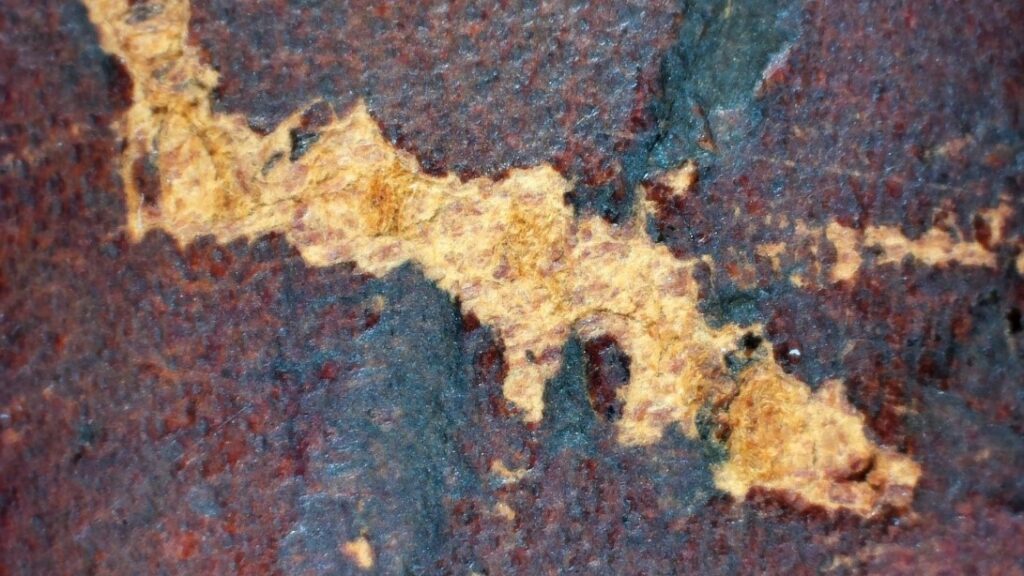

The book’s original spine has been replaced, but it does retain the original front and back covers. These covers were made of many tightly compressed layers of the same rags used to make the paper. This dense tangle of rag fibers can be seen in the magnified image below, which was taken along one of the exposed edges of the book’s front cover.

There is a thin layer of leather wrapped around both covers and the spine. Sometimes, microscopic examination can reveal a follicle pattern in leather, which helps conservators identify the type of animal skin used to make it. I was not able to identify a clear follicle pattern through my examination, but there is a good chance that this book’s leather was made of calfskin.

Knowing the composition of the dictionary’s paper and binding will help us preserve it in good condition for many years to come. If you’d like to see it yourself, contact rare book librarian Stewart Plein at Stewart.Plein@mail.wvu.edu or (304) 293-0345.