Manuscript Fragments and Repurposed Realities

Posted by Admin.July 18th, 2022

By Destinee Harper

This summer, I worked as an intern in the Rare Book Room studying manuscript leaves and fragments in antiquarian books. I was terrified. What if I dropped one of the books? Turned a page too fast and ripped it? Committed a major faux pas to the world of rare book study?

I did make a few blunders (note: do not compliment the condition of a book “considering its age”), but I avoided most of the nightmares that worried me most. I did not break anything, rip off any covers, etc. Something unexpected did happen, though—my attitude toward books changed entirely.

I had always appreciated stories and the power of a good book. But it did not occur to me that the most valuable books might not be the signed first editions, but the book bound in manuscript. I had never thought about the value of a book’s binding or the history it might share. Rarely did I think about what happened to the volumes upon volumes of manuscript after the invention of the printing press. Now, though, these are the first things I think of when an old book is placed in front of me.

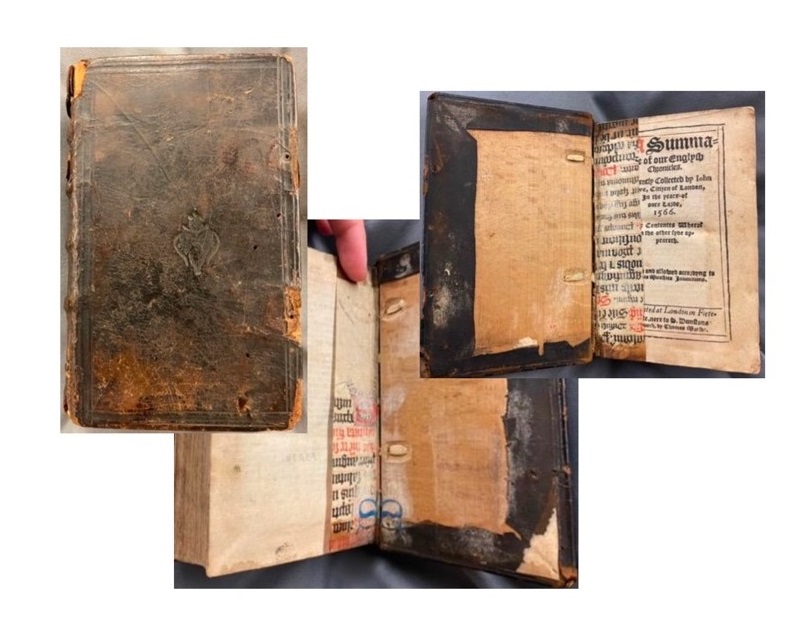

The Rare Book Room’s collection of manuscript fragments is varied and encourages those that study it to consider the multiple repurposed realities manuscripts faced as technology progressed. This 1566 edition of A Summarie of our Englyſh Chronicles by John Stowe, for example, has manuscript fragments hiding inside its covers. Their intended purpose is unclear. They are too small to be pastedowns or endpapers, and it is not possible to discern if they reinforced the binding in any way. Perhaps they were cut. It is a mystery that we might never uncover. What we are sure of, though, is that these fragments, like many in our collection, were recycled and used as scraps for binding purposes. After the invention of the printing press, manuscript fragments were considered junk—certainly not valued as they are today!

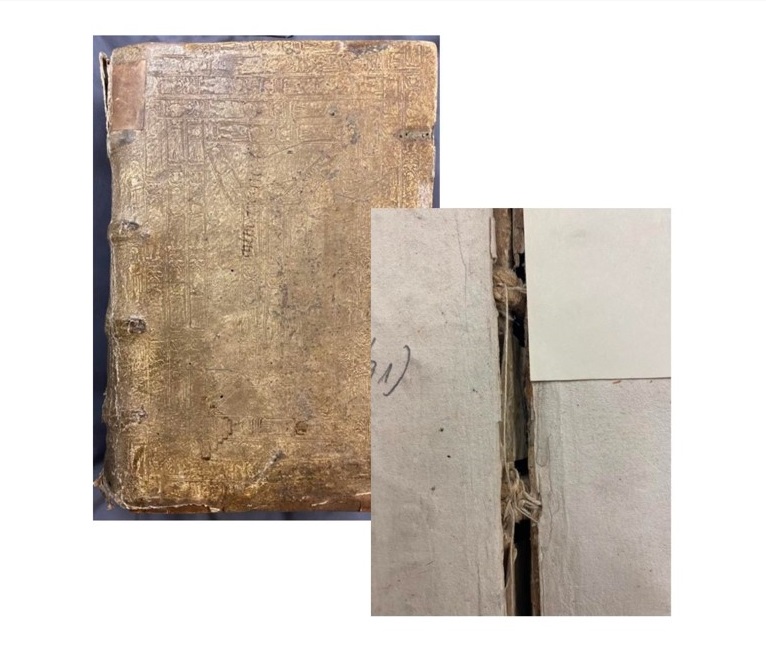

Even further hidden in the binding are the fragments inside this Bible printed in 1493. The fragments are barely visible peeking through the spine. Can you spot them?

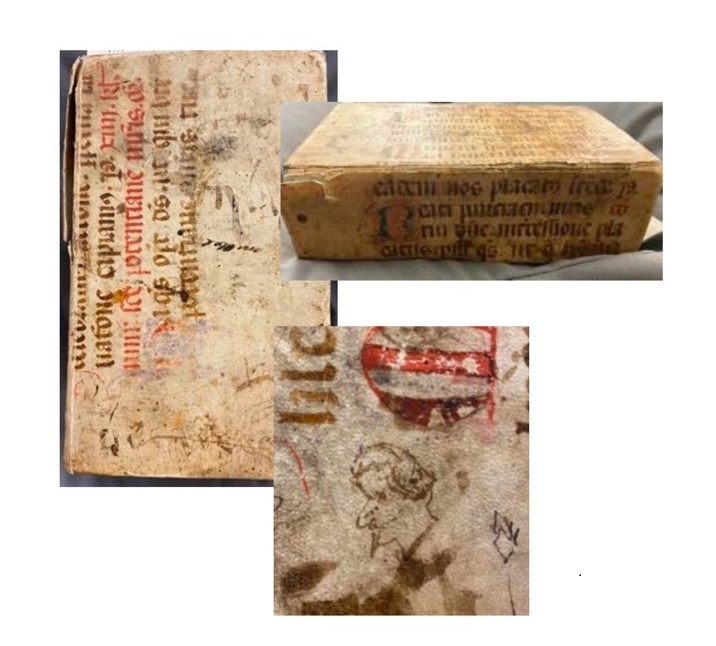

This dictionary, rather than having manuscript fragments tucked away inside, is bound in a manuscript leaf. On its back cover is a doodle of a man. The doodling is likely contemporary to the book, which was printed in 1731.

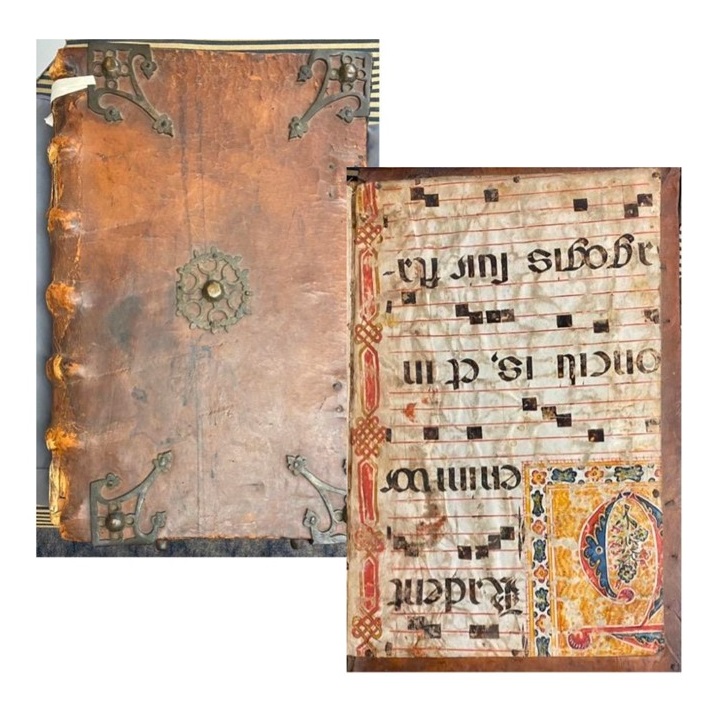

Fragments come in all shapes and sizes. This choir book, commissioned by Andres Camacho in 1450, is huge. There is an elaborate manuscript fragment used as a pastedown inside the rear cover. The decorative initial is gorgeous, but this fragment was cut, repurposed, and meant to be ignored in the back of the book.

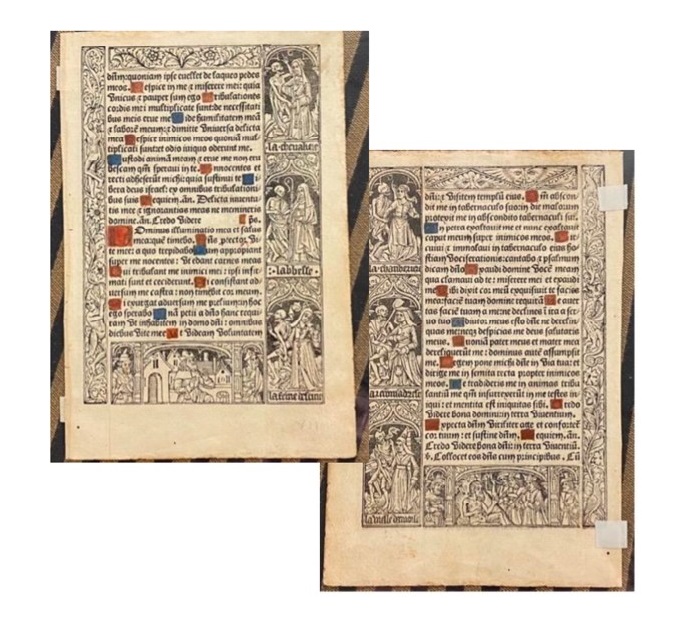

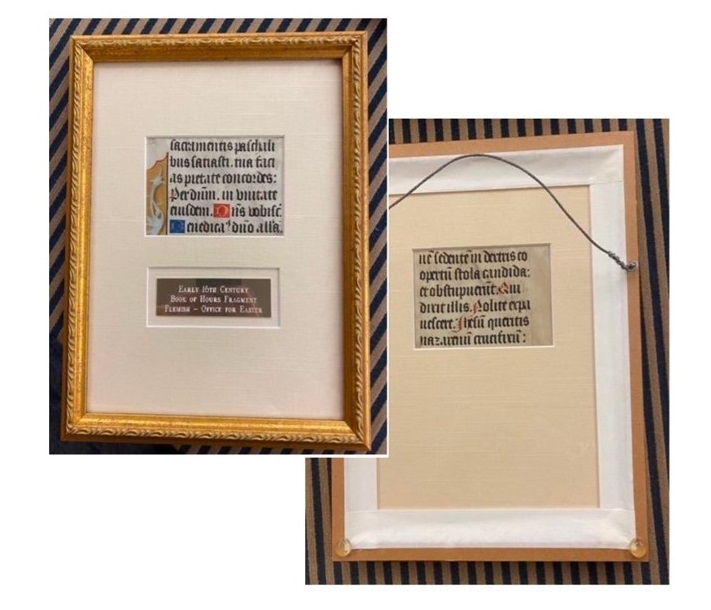

Some manuscript fragments survived long enough to be sold as antiques. The library has a small but impressive collection of individual leaves like this Book of Hours fragment. This leaf was printed then hand illuminated, meaning a scribe decorated the capital initials by hand after the text was printed. This single leaf is worth hundreds of dollars!

Collectors often sell individual leaves rather than full manuscript texts because they can increase their profit this way. Some go so far as to cut leaves into smaller pieces, which they then frame and sell.

This process of deconstructing and selling manuscript texts makes Fragmentology—the study of manuscript fragments—quite difficult. The pieces are scattered and oftentimes impossible to reassemble. Still, we are able to learn a lot about early book and manuscript history from each fragment and how they were repurposed!

If you are interested in learning more about West Virginia University’s manuscript collection, you can read this bibliography I created as part of my internship that provides in-depth descriptions and pictures of each fragment in the collection. I also designed this slideshow with pictures and information about the collection that you are welcome to share in a classroom setting.

You can also schedule a visit to see the library’s collection in person!