Signatures

Posted by Mary Alvarez.March 11th, 2024

Written by Devon Lewars

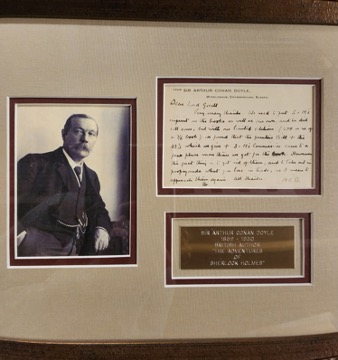

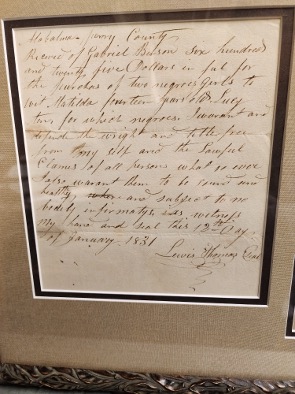

In today’s standards, it is frowned upon to tear signatures from their page, however, this used to be a common practice amongst collectors. Signatures were often torn from pages of correspondence, deeds, or even wills. The West Virginia and Regional History Center (WVRHC) currently owns multiple archives and manuscripts (A&M) collections that include items of this nature. A collection of signatures was donated to the WVRHC and a few of those pieces are currently on display in the rare book room.

Similarly, in the past, it was common for individuals to loot sites of archeological significance. An artifact is most valuable when it is found in relation to the age of the soil it rests in. If an object is taken from its historical context, it loses value.

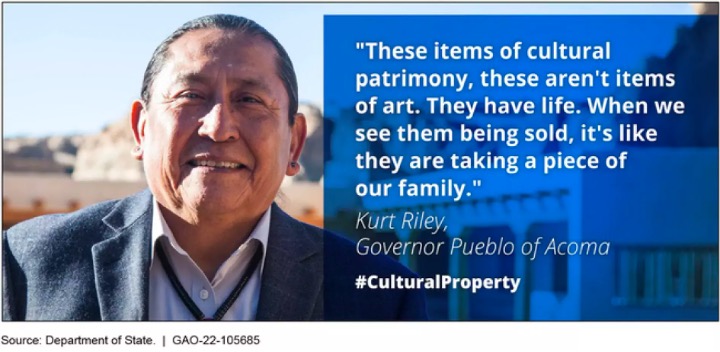

In the 1970s, five cultural shields of the Acoma Pueblo (Uh-Ko-Muh Pweh-Blo) village of New Mexico vanished from the home of one family. Although under the protection of one caretaker, the shields were collectively owned by every member of the tribe. The shields, when not used in ceremony, were kept in a cold, dark room. They were part of the tribe’s identity, never to leave the Acoma or be destroyed.

In 2016, after nearly 50 years, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the FBI brought photos of one shield to Acoma. The shield was pictured under fluorescent lights and to be sold at EVE, a Paris auction house. Elena Saavedra Buckley, an editor of the HighCountryNews perfectly describes the shield as “round and rawhide, it showed a face in its center, with black, low-scooped horns, like a water buffalos, and a red-lipped, jagged smile. The rich colors of the paint — emerald green, with red, blue and yellow radiating from the face’s edges — seemed to have survived the years unfaded, even as they flaked and mottled the surface. Two feathers with rusted tips, like an eagle’s, hung at each side, pierced through the leather and strung by their quills.”[i] It wasn’t until the evening of November 15, 2019, that the shield was seen by members of the tribe. Acoma leaders prayed alongside the shield past midnight that day, never leaving its side.

Between 2016 and 2019 the Acoma Pueblo fought desperately against the convoluted systems of Paris’s government and the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Instances of looting and/or stealing artifacts from native reservations have been occurring for centuries. The repatriation of these artifacts is a slow and often grueling process for the tribes and those that see the loss of the items rarely get to see its return.

Although the donated signatures in our care have lost their context, they provide an opportunity for current generations to reflect on practices of the past. The WVRHC and other institutions that make research accessible do not condone the tearing or cutting of historical documents.

Courtesy of West Virginia & Regional History Center – Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

For further discussion of this collection, refer to Stewart Plein, Curator of Rare Books at the history center and frankly, a wonderful person to chat with. To learn more about current processing standards speak to Jane LaBarbara, Head of Archives and Manuscripts and a strong advocate for the protection and accessibility of archival collections.

[i] Buckley, Elena Saavedra. “Unraveling the Mystery of a Stolen Ceremonial Shield.” HighCountryNews, August 1, 2020. https://www.hcn.org/issues/52.8/indigenous-affairs-unraveling-the-mystery-of-a-stolen-ceremonial-shield.