Rediscovering the West Virginia Musicians Who Fought for Equal Suffrage

Posted by Mary Alvarez.March 20th, 2023

Written by Greg Leatherman

An all-male marching band from Keyser, West Virginia physically defended suffragists during a historic parade at our nation’s capital in March 1913. Did they return to Washington for another round in 1917?

No history of the equal suffrage movement is complete without a description of the violence against women who paraded through Washington, D.C. in March 1913. At the local level, however, our understanding of this watershed event remains incomplete. Luckily, contemporaneous newspapers—like those digitized through the West Virginia Newspapers project—provide meaningful insight into how participants expressed suffrage activism before and after this historic parade.

This is especially true for activists from rural areas. For example, newly digitized resources prove that an all-male community band from Keyser, WV wielded musical instruments against the riotous mob that attacked the 1913 equal suffrage parade. Moreover, a mysterious photograph appears to indicate that they also participated in a second suffrage protest in 1917. This post offers recently discovered proof of the band’s first date with destiny, and compelling evidence of their second.

Descending on DC

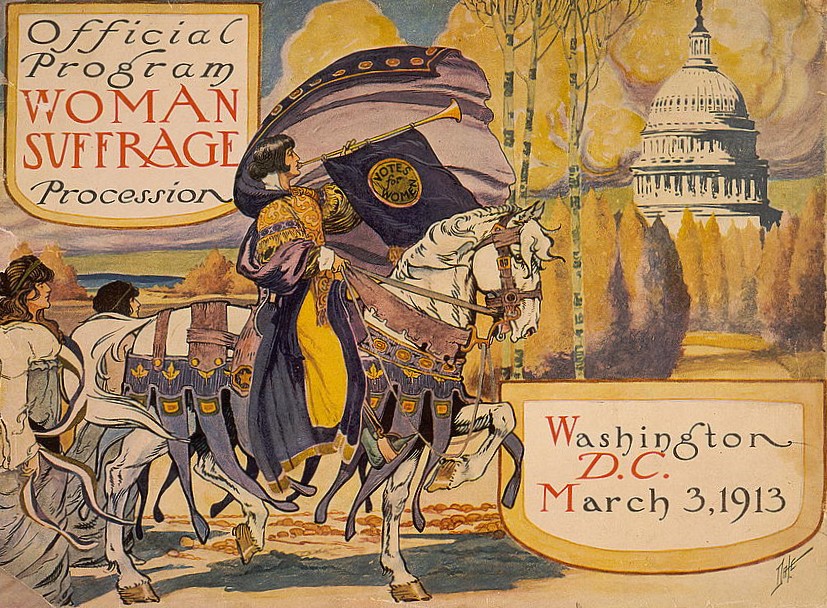

Organized by Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the 1913 march on Washington was scheduled for March 3, i.e., the day before the first inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson. Excitement over this first national suffrage march on the capital had been building for months, but it exploded into a full media frenzy in the final three weeks as “General” Rosalie Gardiner Jones led a group of several hundred “suffrage hikers” on a long march out of New York City and toward Washington. From West Virginia alone, over 100 women from the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, the Charleston Equal Suffrage League, the Wheeling Women’s Suffrage Association, and other organizations journeyed to Washington.

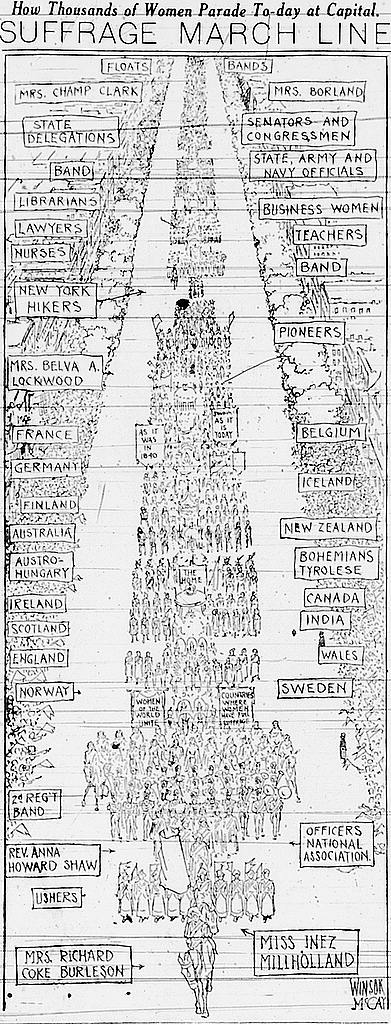

The parade and demonstration included 5,000 women from various racial and social backgrounds, but it also included several hundred men. For example, the Oakland Republican reported that men belonging to a community band from Keyser, West Virginia would “take part in both the suffragette and inaugural parades.”

The band’s expenses were covered through the assistance of Jacob Gabriel Moody, a Keyser native who directed the National Guard’s 2nd Regiment Band of Washington, DC. They may have also received support from NAWSA, which sent letters to bandmasters across the nation inviting them to join the parade. This was a smart move. Not only did such bands add an air of celebration to the event, but they would end up on the frontlines of an historic clash.

Clearing a path through history

The afternoon of March 3 was warm and overcast, with little wind. As the parade started down Pennsylvania Avenue, the 153-member 2nd Regiment National Guard band played rousing suffrage songs. Though impressive, they were outnumbered by 100,000 onlookers, including scores of drunken rowdies angered by the demands of the suffragists. However, the 2nd Regiment was not alone. The College Equal Suffrage League of New York and the New York State Woman Suffrage Party brought smaller bands, while all-female musicians comprised the 23-member Missouri Ladies Military Band. As for the 26-man Keyser Municipal Band—aka McIlwee’s Band—they marched with the hikers led by “General” Jones.

Seeing the crowd swell, parade organizers asked the Missouri band to move forward, start playing, and clear a path. The band did so from a position immediately behind their horse-mounted Grand Marshal, Jenny May Burleson of Texas. Still, spectators shouted their disapproval—and the 575 police officers standing along the parade route were unable to keep the peace. After ten blocks of slow progress, the flimsy crowd barriers failed, and the turbulent pressure of what Burleson called a “horrible, howling mob” squeezed the parade to single-file formation.

The surging mob tripped, grabbed, spat on, and shoved the female marchers. Signs and banners were seized and shredded. Flowers were plucked from coats, and flags were snatched and burned. Men taunted the marchers with insults such as “old hens,” while women of the West Virginia delegation were derided as dirty “snake hunters” and “coal diggers.”

It wasn’t just the women being attacked. One man who marched with Jones’ “suffrage hikers” struggled to keep the American flag he carried from being dragged through the dirt. Social status did not provide any advantage, either. When a congressman’s wife asked a police officer to clear a path, he shouted, “If my wife was where you are, I’d break her head!”

Despite this chaos, many marchers fought back. Inez Millholland, who rode a white horse near the front of the parade, claimed to have “slashed a drunken lout across the face with her riding crop…”

McIlwee’s Band also took a few shots. According to the Keyser Tribune, “The Missouri Girl Band, headed by Mrs. Champ Clark, was directly ahead of the Keyser Band, and the unruly crowd, taking advantage of the girls, succeeded in closing the line and marching was impossible. At this time the Keyser boys took things into their own hands and forced the mob back. Ginger’s big bass made a good battering ram and by strenuous work and the assistance of a squad of Boy Scouts, the band maintained a small space and kept the line moving until aid came from the cavalry troops. . .”

The large man behind that “big bass” was tuba player Forrest Guy “Ginger” Davis, who also served as the Keyser Chief of Police. Davis was a lifelong law enforcement officer elected to three terms as the Sherriff of Mineral County (as a Democrat in 1932, 1940, and 1948). He also served more than thirty years as Keyser Chief of Police. Known for his energetic and tactful approach to policing, Davis was already in his second decade as the band’s business manager.

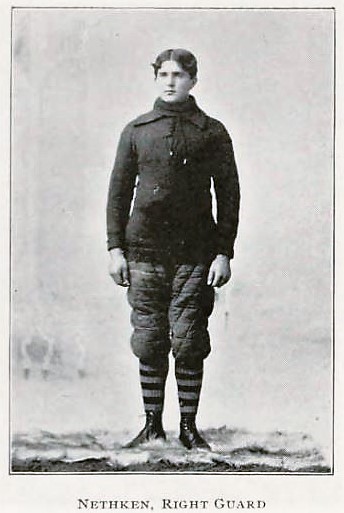

Alongside Davis fought Mineral County Sherriff, Charles Ervin “Mighty” Nethken, a former standout football player for the WVU Mountaineers who was renowned for his physical strength. Nethken won the Stephen B. Elkins gold medal as the Mountaineer’s best player after the 1895 football season and is listed as a guard on WVU’s official All-Time team. In the school’s Monticola yearbook, Nethken was compared to legendary strongman Eugen “Mighty” Sandow, and the nickname stuck even after he graduated. Like Davis, Mighty Nethken served as the Mineral County Sheriff three times (elected as a Democrat in 1904, 1912, and 1920). After his third term, he also served for 25 years as a judge on the WV Public Service Commission.

Between these imposing lawmen, a few members of the Keyser Fire Department, and several railroad employees, McIlwee’s Band had plenty of muscle to withstand the onslaught. They may also have benefitted from teamwork skills developed while playing together on the Keyer baseball team.

As for the Boy Scouts, around 1,500 were brought in to help the police. Averaging just 14-years in age, they were armed with long wood staves, which they used to hold back the crowd, then to form stretchers for carrying wounded women to ambulances that “came and went constantly for six hours.” Six squads of young men from the Maryland Agricultural College (now called the University of Maryland) also fought the mob. Nonetheless, at least 100 injured women were transported to the local Emergency Hospital.

In the days after the parade, national headlines contrasted the peaceful suffragists against the violent mob. More details emerged as a congressional committee investigated the failures of the Washington police. Among those who testified was “Mrs. Champ Clark,” i.e., the wife of the Speaker of the House. Most shockingly, the committee concluded that off-duty police officers encouraged attacks against the parading women.

As for McIlwee’s Band, the Keyser Tribune reported, “After the parade the band was publicly lauded by Miss Millholland, General Jones, and other leaders.”

The band also played concerts during the inaugural festivities. According to the Keyser Tribune, “In the Inaugural parade, the band headed the Civic Division and led the President’s own club, the Wilson Democratic League, from Trenton, NJ. This was certainly an honorary position and one that might have been given to a larger band.”

The famous Keyser band

Under Professor William H. “Will” McIlwee, who was in his second decade of leading the Keyser band, local musicians played at fairs, athletic events, church revivals, lectures, fundraisers, weddings, funerals, and more. In concert settings, they were called McIlwee’s Concert Orchestra, and their weekly summer performances from an electrified bandstand on Prep Hill in Keyser were attended by as many as 4,000 locals in 1914. They also toured on a limited basis. For example, the band entertained attendees at the 1915 reunion of the Grand Army of the Republic in Washington, as well as the 1916 reunion of Confederates at Franklin, WV.

As one admiring Keyserite wrote, “The Band is the greatest institution of life; when it plays all individual differences cease; we are no longer Republican or Democrats; Prohibitionists or Socialists; Methodists or Baptists; Catholics or Masons, we are humans of a common brotherhood, ready to put our shoulders to the common wheel and boost our town or our state or our country higher into the limelight of prestige and prosperity.”

A commitment to equality

After the 1913 parade violence, Mighty Nethken appears to have stopped performing with McIlwee’s Band. However, he continued to speak in support of equal suffrage. For example, when Keyser hosted a suffrage rally in July 1916, McIlwee’s Band played first, then Nethken introduced a young activist who’d marched with them in Washington parade.

As the Keyser Tribune described the scene, “Notwithstanding the rain Miss Eudora Ramsey… addressed a large crowed on Main street last Monday night on behalf of the equal suffrage amendment. McIlwee’s band put the people in a receptive mood, when Sheriff Nethken gallantly introduced the fair speaker …”

In September 1916, McIlwee’s Band performed at a suffrage picnic in Franklin, WV, which featured speeches from Dr. Harriet Jones, Dr. Duncan Lindly Sloan, and Alma B. Sasse. A month later, Canadian suffrage activist Nelly McClung spoke at the Keyser Music Hall after being introduced by Mighty Nethken and local activist Nancy C. “Nan” Hepburn.

When Democratic gubernatorial candidate John J. Cornwell campaigned at the Keyser Music Hall in October 1916, he also sought the support of women. For months, Cornwell publicly courted the support of the West Virginia Equal Suffrage Association, and now that he was teaming with a band that marched with suffragists, advanced notice for his Keyser speech stated, “Ladies are especially invited. McIlwee’s Concert Band will furnish music.”

Cornwell even used the front page of the newspaper he owned, the Hampshire Review, to endorse Mighty Nethken in the Democratic primary for the second congressional district seat vacated by Nethkin’s political mentor, William Gay Junior” Brown, Jr., who died in March 1916. Congressman Brown’s widow was suffragist Izetta Jewel (1883-1878) who later became the first American woman to deliver a seconding speech for a major presidential nominee when she supported John W. Davis (1873-1955) of West Virginia. While campaigning for Davis at the Keyser Music Hall on the day before the 1924 election, she was joined by Nethken. Again, McIlwee’s Band provided the music.

Solving a photographic mystery

In January 1917, the Piedmont Herald reported, “The committee in charge of the inauguration ceremonies at Washington are corresponding with the famous McIlwee band of this place, with the view of securing them for the next inauguration This band made a great hit at the last inauguration in leading the suffrage parade.”

The invitation was also reported by the Mineral Daily News, which added, “Of course the Band will make a contract if there is nothing in the way. The Keyser band made such a hit last inauguration that the committee has given them first consideration.”

As March arrived, the Piedmont Herald confirmed, “Chief F.G. Davis has the arrangements nearly perfected for the McIlwee Concert Band to attend the inauguration…”

Nonetheless, unlike the band’s heroics before Woodrow Wilson’s first inauguration, their performance during his second one did not receive any post-event press coverage. The reasons for this omission were multifaced. First, the Keyser band was not listed in the official inaugural parade formation. This suggests they were in town for auxiliary events, such as another historic suffrage gathering. Second, there is evidence that their association with suffrage negatively impacted band members as political candidates.

To understand, consider that West Virginia voters narrowly elected Democrat John J. Cornwell as their new governor in 1916. After Cornwell’s election, hundreds of citizens from Mineral County braved a rainstorm to travel to his home in Romney where 1,500 heard him give a short address. Once there, they congratulated and serenaded the victorious Democrat, led again by McIlwee’s Concert Band and speaker, Mighty Nethken.

However, Nethkin was not a winner that year. He lost his congressional primary in a landslide. Moreover, in the general election, Ginger Davis lost his first run for Mineral County Sheriff. These stinging defeats marked the only political losses either man ever experienced, and it’s possible that their support of an equal suffrage measure that lost by a greater than 2 to 1 margin among Mineral County’s all-male electorate contributed to these losses.

Local support for the band also seemed to wane. After a smaller than anticipated crowd attended one of their concerts in 1916, Mineral Daily News editor William Henry Barger scolded his readers, stating, “If some cheap, ragtime and dance orchestra from out of town had given the concert, there is no doubt but that the auditorium would have been filled, but when an orchestra, probably the best in three states, and an orchestra that belongs to Keyser offers a concert of standard world-famous selections only a few come. Strange, isn’t it?”

As an organization led by Democrats, band members may have also been reluctant to publicize plans to protest a Democratic president’s opposition to nationwide equal suffrage, even after it was endorsed in the 1916 Democratic Party Platform. Nonetheless, evidence suggests this is exactly what they did.

As with the 1913 parade, the 1917 White House picket was planned by Alice Paul. It began on January 10—without McIlwee’s Band—but during the week preceding the inaugural celebration, organizers planned to increase public pressure through what they labelled, “The Siege of Jericho.” For this, they would need trumpets.

According to the National Woman’s Party (aka Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage), protestors intended to dramatize the sixth chapter of Joshua by marching around the White House for six days, “Then, on the seventh day—next Sunday to be exact—with their number swelled by thousands of women from all parts of the country, they shall compass the ‘city of Watchful Waiting’ seven times, and seven priestesses, bearing the suffrage ark, ‘shall blow with trumpets.’

“‘And it shall come to pass that when they make a long blast with the ram’s horn, and when ye hear the sound of the trumpet, all the people shall shout with a great shout and the walls of the city shall fall down flat.’”

However, the pre-inauguration picket did not draw nearly as many participants (or spectators) as the 1913 parade. For example, the West Virginia woman who intended to carry her state’s banner around the White House grounds for this siege did not make it and was replaced by a local.

There were three main reasons for lower numbers. First, the picket went on for months, so that only a portion of the total number protestors were active at any given time. Second, the “siege” elements were downplayed after March 1, when an intercepted German telegram made it clear to most Americans that the nation was headed for war. Third, a rainstorm pelted the women who did picket—and the two bands that joined them were thwarted by a continuous downpour that “silenced the drums” and “strangled” the horns.

As a result, the drenched marchers made only four trips around the White House grounds, and when the President and Mrs. Wilson crossed the picket line in their limousine, they refused to even look at the protestors.

In her memoir, suffrage activist Dorothy Stevens recalled, “It was a day of high wind and stinging, icy rain… when a thousand women, each wearing a banner, struggled against the gale to keep their banners erect. It is always impressive to see at a thousand people march, but the impression was imperishable when these thousand women marched in rain-soaked garments, hands bare, gloves roughly tourn by the sticky varnish from the banner poles and the streams of water running down the poles into the palms of their hands. It was a sight to impress even the most hardened spectator who had seen all the various forms of the suffrage agitation in Washington… Two bands whose men managed to continue their spirited music in the driving rain led the march…Vida Millholland led the procession carrying her sister’s last words, ‘Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?”

The suffragists had their own band led by Lavinia Dock. Doris Stevens played the snare drum; and before her death in November 1916, Inez Milholland played accordion. In her memoir, however, Stevens specifically referenced two bands of men who played during the White House picket of Sunday, March 4, 1917.

One photograph taken on the day of the March 4, 1917 picket shows an unnamed band marching around the executive mansion while women carry flags and banners behind them. The rainy scene includes policemen in raincoats, a drummer with his own coat draped over his instrument, and a large tuba player. To those familiar with the famous Keyser band, the tuba player resembles Ginger Davis, and the drummer is a ringer for Professor McIlwee.

Although this photographic evidence is not conclusive, it strongly suggests that music at the “Great Picket” of March 4, 1917 was provided by McIlwee’s Band. If so, this second appearance in support of suffrage activists says even more about the band’s convictions than their heroics during the 1913 parade. One might even conclude that a second appearance places the all-male Keyser band in the vanguard of grassroots support for suffrage.

Conclusion

The perseverance of marching suffragists against opponents at all levels of society—from politicians to drunken rowdies—gained them numerous allies. For example, national headlines about violence at the 1913 equal suffrage parade convinced many that the suffrage movement would not be easily derailed, while photographs of women arrested for “obstructing traffic” during the 1917 White House picket campaign, including some from West Virginia, did much to convince the public that activist women were on the right side of history.

Although progress toward equal suffrage slowed during World War I, Governor Cornwell called a special session for March 1920, during which the WV state legislature ratified the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Six months later—after 36 hard fought states ratified the historic amendment— a woman’s right to vote became federal law. As described above, McIlwee’s Band played a supporting role in winning that right, and their brassy defense of equal suffrage deserves remembrance as part of West Virginia’s feminist heritage.

Blog contributed by Greg Leatherman. Greg is a Keyser native now residing in Florida.

Notes:

- Future researchers interested in this topic may benefit from examining relevant records from NAWSA, the National Woman’s Party, and WV suffrage organizations. Further photographic corroboration may also be possible using sources available through the WVU Library Systems, the Library of Congress, and family records.

- The band roster as of September 1914 was: Bandleader, W.H. McIlwee; Manager, F.G. “Ginger” Davis (bass); President, Samuel T. Merryman (Eb clarinet); Treasurer, Charles W. Bell (baritone); Leo C. Wilcox (trombone); Alfred W.”Bill” Merryman (trombone); Albert F. Rice/Ries (alto); Henry W. Clark (alto); Leslie O. Brotemarkle (alto), Emmitt C. Kolkhorst (alto), Ira L. Ravenscraft (first cornet), Floyd M. Mills (solo cornet), John W. Johnston (solo cornet), Dennis “Dennie” T. Rasche (solo clarinet), Walter G. Kephart (3rd Bb clarinet), Arthur W. Cross (2nd bf clarinet), Lloyd L. Mills (2nd Bb clarinet), Leonard E. “Eugene” Cross (1st Bb clarinet), Lawrence E. Kolkhorst (solo Bb clarinet), Frank R. Troy (flute and piccolo), Walter S. Decker (baritone saxophone), Clatus L. Shaffenaker (tenor sax), Harry E. Hannas (Bb bass), Henry W. “Warren” Kolkhorst (solo bass), Robert E. Rice (snare drum), Felty E. “Ervin” Shelly (snare drum), and Charles H. “Harry” Davis (bass drum).

- McIlwee’s band was not the only musical outlet for these men. For example, by 1916, saxophonist Walter S. Decker found a national publisher for his musical compositions. Another member from a later iteration of the band, Howard S. Pyles, became a longtime orchestral conductor for the Columbia Broadcasting Company.

- A few bandmembers were not from Mineral County, but neighboring Garrett County, Maryland, where they played in the Mountain City Band of Oakland under the visiting instruction of Prof. McIlwee. On occasion, Keyser band members (e.g., Davis, Decker, and Schaffenaker) also supported the Mountain City Band, as they did when joining them to entertain a Democratic political meeting at Oakland in 1911 Compared to Mineral County, Garrett County was a suffrage hotspot. As a result of this relationship, before the 1917 picket, the McIlwee’s Keyser Band added talented cornet player, Roy F.T. Hinebaugh as a permanent member. Hinebaugh—along with Charles I. Liller, Calvin H. Echard, Wallace “Wall” E. Brown—also marched with the Keyser band in the 1913 parade as guest musicians from the Mt. City Band. This was a semi-regular occurrence, as these same men (and others) also temporarily joined what the Oakland Republican called the “famous Keyser band” in 1910, 1915, 1917, etc. Some switched between the two bands, as needed. For example, Dennis T. Rasche, was listed as an official member of the Keyser band in 1914, yet he was again a visiting musician from the Mt. City Band in 1915.

- Doris Stevens provided a list of songs played during the 1917 picket: ‘Forward Be Our Watchword;’ ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic;’ ‘Onward, Christian Soldiers;’ ‘The Pilgrim’s Chorus,’ from Tannhäuser; ‘The Coronation March; from Le prophète; the ‘Russian National Hymn;’ and ‘The Marseillaise.”

Sources:

This research was made possible thanks to digital resources provided by the West Virginia Newspapers site hosted by Potomac State College of West Virginia University.

- Pittsburgh Press. 28 Oct 1894, p. 13; 21 Mar 1895, p. 1; 03 Jan 1896, p. 4;

- Wheeling Daily Register. 08 Jan 1896, p. 1;

- Mineral Daily News/Mineral Daily News-Tribune. 26 Jul 1912, p. 2; 07 Aug 1912, p. 1; 10 Aug 1912, p. 1;15 May 1913, p. 1; 16 May 1913, p. 1; 27 May 1913, p. 1; 28 May 1913, p. 1; 01 Jul 1913, p. 1; 08 Jul 1913, p. 1; 04 Nov 1913, p. 1; 13 Apr 1914, p. 1; 07 May 1914, p. 1; 01 Jul 1914, p. 1; 09 Sep 1914, p. 1; 18 Sep 1914, p. 1; 19 Sep 1914, pg. 1; 21 Jun 1915, p. 1; 02 Mar 1916, p. 2; 22 Mar 1916, p. 2; 04 Apr 1916, p. 3; 22 May 1916, p. 2; 03 Jun 1916, p. 4; 05 Jun 1916, p. 2; 14 Jul 1916, p. 1; 15 Aug 1916, p. 1; 19 Sep 1916, p. 1; 18 Oct 1916, p. 4; 21 Oct 1916, p. 01; 23 Oct 1916, p. 03; 24 Oct 1916, p. 1; 25 Oct 1916, p. 1; 26 Oct 1916, p. 1; 23 Nov 1916, p. 2; 03 Jan 1917, p. 1; 23 Jan 1917, p. 1; 24 May 1917, p. 4; 04 Jun 1917, p. 1; 26 Jun 1917, p. 2; 25 Oct 1917, p. 1; 29 Nov 1918, p. 2; 02 May 1920, p. 2; 01 Nov 1920, p. 1; 03 Nov 1920, p. 2; 02 Jan 1924, p. 1; 04 Apr 1924, p. 1; 07 Mar 1925, p. 2; 27 Nov 1925, p. 1; 02 Sep 1932, p. 1; 11 Feb 1936, p. 1; 24 Jun 1936, p. 1; 07 Jun 1955, p. 2; 03 Apr 2003, p. 1;

- Tampa Tribune. 29 Dec 1912, p. 8; 05 Mar 1917, p. 3;

- Dunkirk Evening Observer. 28 Feb 1913, p. 1;

- Piedmont Herald. 07 Mar 1913, p. 7; 11 Dec 1914, p. 10; 20 Oct 1916, p. 5; 02 Mar 1917, p. 9; 14 Jul 1916, p. 1; 21 Jul 1916, p. 5; 02 Mar 1917, p. 9; 02 Aug 1918, p. 5; 31 Oct 1924, p. 1; 03 Nov 1938, p. 8; 10 Nov 1932, p. 1; 10 Aug 1939, p. 6;

- Keyser Tribune. 20 Oct 1911, p. 2; 22 Nov 1912, p. 2; 20 Dec 1912; 07 Feb 1913, p. 4, 5; 07 Mar 1913, pp.1, 5; 14 Mar 1913, p. 2; 21 Mar 1913, p. 1; 11 Jul 1913, p. 1; 12 Dec 1913, p. 1; 26 Dec 1913, p. 1; 25 Sep 1914, p. 2; 11 Dec 1914, p. 1; 12 Nov 1915, p. 2; 14 Apr 1916, p. 4; 26 May 1916, p. 2; 21 Jul 1916, p. 2; 22 Sep 1916, p. 2; 20 Oct 1916, p. 2;

- Washington Post. 05 Mar 1913, p. 3; 18 Mar 1913, p. 2; 04 Mar 1917, p. 6; 05 Mar 1917, p. 2;

- Fairmont West Virginian. 25 Mar 1913, p. 1; 10 Sep 1917, p. 4;

- Kenosha Evening News. 26 Dec 1912, p. 4;

- Washington Herald. 27 Dec 1912, p. 4;27 Feb 1913., pp. 1-2; 04 Mar 1913, pp. 1, 4; 06 Mar 1917, p. 1;

- Buffalo Sunday Morning News. 19 Jan 1913, p. 18;

- Pittsburgh Daily Post. 04 Mar 1913, p. 1; 03 Aug 1916, pg. 1;

- Baltimore Sun. 04 Mar 1913, p. 2; 11 Mar 1913, p. 1; 23 May 1918, p. 3;

- Baltimore Evening Sun. 04 Mar 1913, pp. 3, 6.

- Wheeling Intelligencer. 04 Mar 1913, pp. 1, 8; 05 Mar 1917, p. 4;

- St. Louis Post Dispatch. 04 Mar 1913, p. 6.

- Nashville Tennessean. 04 Mar 1913, p. 1;

- Alexandrian Gazette. 04 Mar 1913, p. 1;

- Clarksburg Daily Telegram. 04 Mar 1913, pp. 1, 9;

- Moberly Weekly Monitor. 04 Mar 1913. p. 1;

- Houston Post. 07 Mar 1913, p. 1;

- Washington Times. 10 Mar 1913, p. 7; 13 Mar 1913, p. 1; 16 Apr 1913, pp. 1-2; 02 Mar 1917, p. 5; 05 Mar 1917, p. 10;

- Bluefield Daily Telegraph. 11 Mar 1913, p. 1;

- Washington Evening Star. 06 Mar 1913, pp. 1,2; 17 Mar 1913, p. 1;25 Feb 1917, p. 17; 04 Mar 1917, pp. 4, 14,15; 05 Mar 1917, p. 2; 06 Mar 1917, p. 15;

- Saskatoon Daily Star. 26 Mar 1913, p. 4;

- Oakland Republican. 21 Jul 1910, p. 5; 23 Feb 1911, p. 5; 06 Mar 1913, p. 5; 10 Jun 1915, p. 4; 24 May 1917, p. 1; 11 Oct 1917, p. 4; 18 Dec 1924, p. 5; 02 Mar 1933, p. 3;

- Hampshire Review. 24 May 1916, p. 1; 31 May 1916, p. 1; 15 Nov 1916, p. 1; 22 Nov 1916, p. 1; 25 Feb 1920, p. 1;

- Shepherdstown Register. 19 Oct 1916, p. 4; 19 Oct 1916, p. 4;

- Clarksburg Exponent. 24 Oct 1917, p. 4;

- Preston County Journal. 10 Dec 1914, p. 1; 30 Sep 1920, p. 5;

- Cumberland News. 06 Jan 1953, p. 7;

- Mountain Echo. 30 Oct 1952, p. 3; 28 Jun 1956, p. 4; 15 May 1958, p. 3;

- Stevens, Doris (2008). Jailed for Freedom: The Story of the Militant American Suffragist Movement, pp. 92-100. Lakeside Press, R.R. Donnelly & Sons, USA.

- “Boy Scouts at the 1913 Suffrage Parade,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/boy-scouts-at-the-1913-suffrage-parade.htm (accessed 02/12/2023)/;

- “West Virginia and the 19th Amendment,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/west-virginia-women-s-history.htm (accessed 02/15/2023);

- “What the Boy Scouts Did at the Inauguration,” Boys Life. April 1913, pp. 2-4;

- 1916 Democratic Party Platform. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/1916-democratic-party-platform (accessed 03/29/2020);

- Effland, Anne Wallace (1983). The Woman Suffrage Movement in West Virginia, 1867-1920. Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7361. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7361 (accessed 03/03/2023);

- Monticola of West Virginia University, 1896, pp. 124, 132, 139, 201, 202, 205. A.L. Swift and Co., Chicago; and

- Walton, Mary (2010). “Alice Paul, Brief life of pioneering suffragist (1855-1977),” Harvard Magazine, Nov-Dec 1910. https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2010/11/alice-paul (accessed 02/22/2023); and

- “Eudora Woolfolk Ramsay Richardson,” Dictionary of Virginia Biography. Library of Virginia. https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Richardson_Eudora_Ramsay (accessed 03/02/2023.