5 Recent West Virginia Reads…and One Kentucky

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.November 2nd, 2020

Blog post by Linda Blake, University Librarian Emerita

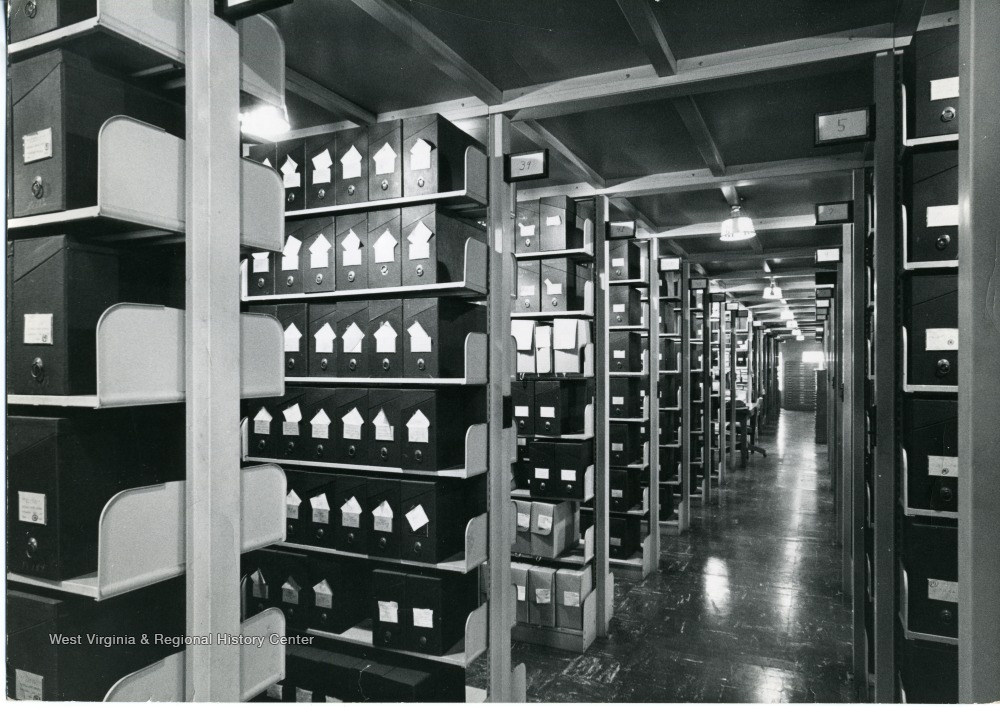

I am always somewhere in the process of reading an eBook, an audiobook, and a book-book, old-fashioned print on paper. Recently I have been migrating toward West Virginia authors and West Virginia history probably because of the in depth look at West Virginia history working in the West Virginia and Regional History Center has afforded me. The books I am featuring in this blog post are all non-fiction, except Ludie’s Life, which is a novel in poetry, and the Kentucky novel, The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek. All include themes of particular interest to Appalachia: the importance of place, family loyalty, and struggle.

Note: Each title links to the WVU Libraries catalog entry. Those held in the West Virginia and Regional History Center book collection cannot be removed from the Center, but those in the Appalachian Collection or the general book collection may be borrowed by WVU faculty, staff, or students. Most West Virginia academic and public libraries should have these titles, or they can be requested through the libraries’ interlibrary loan services.

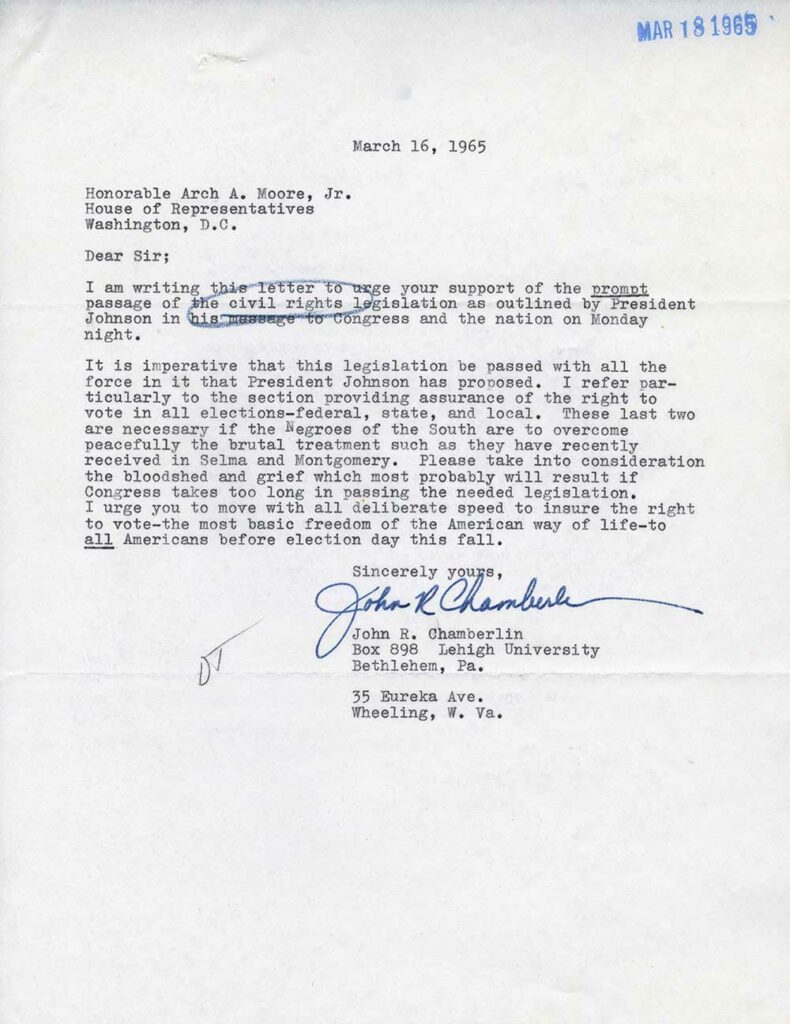

The Buffalo Creek Disaster: How the Survivors of One of the Worst Disasters in Coal-Mining History Brought Suit Against the Coal Company—And Won by Gerald M. Stern. 1977.

In 1972 on a quiet Saturday morning a Pittston Coal Company slurry impoundment broke and flooded Buffalo Creek hollow with 132 million gallons of water creating a 25-foot wall of water and debris. It washed away either all or partially 17 communities along the creek in Logan and Wayne Counties. The disaster resulted in the total annihilation or destruction of homes leaving thousands homeless; the death of 125 men, women, and children; and left behind devastation and guilt-ridden and confused survivors. This book details why this was not “an act of God” as declared by Pittston Coal and the legal battle by over 600 tenacious survivors and family members. The group hired the book’s author’s law firm to represent them in a class action suit. In the 1970s, terms such as post-traumatic stress did not exist, but in a unique move for the time, Stern sued for compensation for “psychic-damage” in addition to property damage and bodily injury. Stern also had to delve into the morass of corporate ownership and its legal implications. This book provides a fascinating account of how the legal case was won.

Diamond Doris: The Ture Story of the World’s Most Notorious Jewel Thief by Doris Payne and Zelda Lockhart. 2019

West Virginians are amazing people full of surprises. Doris Payne is one of these amazing people. She was born in the small segregated southern West Virginia town of Slab Fork during the Depression. She became one of the most notorious jewelry thieves ever. Payne was a woman, and she was Black, but refused to conform to the stereotypes of what a Black woman could accomplish. She used her intellect, good looks, and flair for style to rescue her mother from her abusive father and to rescue herself. How did she accomplish this notoriety? What drove her to steal jewelry around the world? Was she justified? What happened to her as she aged? All the answers are in this fascinating memoir, an autobiography which reads like a novel.

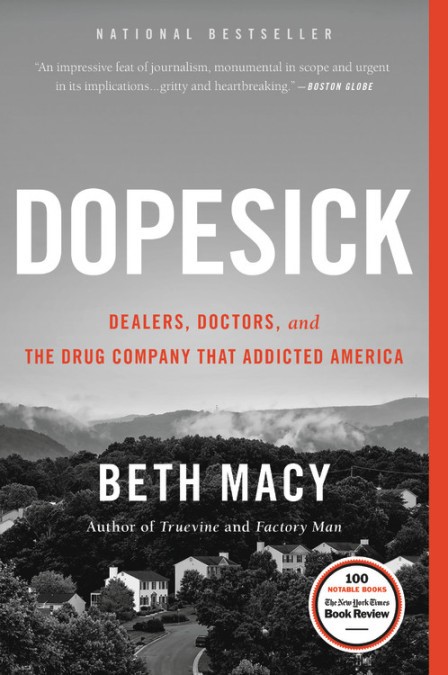

Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America by Beth Macy. 2018

Dopesick is an eye-opener for those of us who thought where we live made us immune to the opioid epidemic. How could opioid addiction, once considered isolated to urban areas, come to small town America and what role did West Virginia play in the epidemic? Macy gives us a very personal and detailed view by tracing the story of some addicts and their families from the beginning of drug abuse. She not only explains how addiction occurs but also the chain from pharmaceutical companies to user, current therapeutic practices, and the justice system’s involvement. The subtitle indicates that Macy points a finger directly at drug companies. This book is not about the oxycotin use in southern West Virginia but about the link between Martinsburg, West Virginia, sitting next to the Baltimore/Washington metropolitan areas, as a wide distribution point for illegal drugs.

Ludie’s Life by Cynthia Rylant. 2006

I am a fan of Cynthia Rylant and I particularly like When I Was Young in the Mountains, a picture book. Rylant is a true West Virginia treasure for the way she captures our traditions and attachment to home with joy and reverence. In Ludie’s Life, a life told in free verse, Rylant again works her magic by giving us Ludie through birth, marriage, childrearing, old age, and death. The book also traces the changes to her coal field community as Ludie observes from her company house. While promoted as a young adult book, I think the themes such as childbearing, illness and death, aging, and loneliness are too raw for youth. For example, Ludie describes her husband’s brother as “a man just teetering on the line between good and bad. No one knew for sure if he was crazy or just plain mean. This much was true: Ludie feared him.” The book is full of truths such as this passage about change “…it seemed to Ludie that little by little life was packing her up for the long journey home. The chickens and chicken pens gone. The hogs gone from the hog lot. No beagle tied to the doghouse. No doghouse.” Maybe you don’t care for poetry, but I promise you that you will fall into Ludies’ Life, see it to its end, and then keep it close by for rereading.

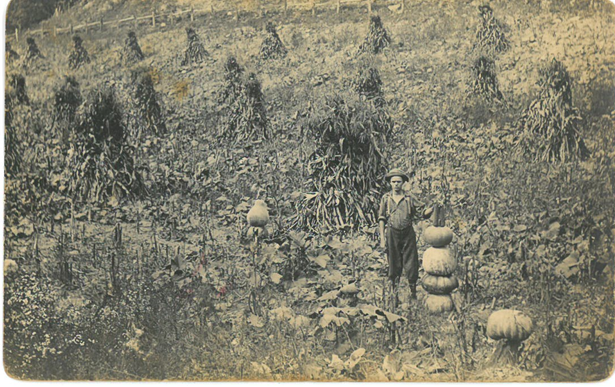

Running on Red Dog Road: and Other Perils of an Appalachian Childhood by Drema Hall Berkheimer

![Running on Red Dog Road: And Other Perils of an Appalachian Childhood by [Drema Hall Berkheimer]](https://news.lib.wvu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/image-3.jpeg)

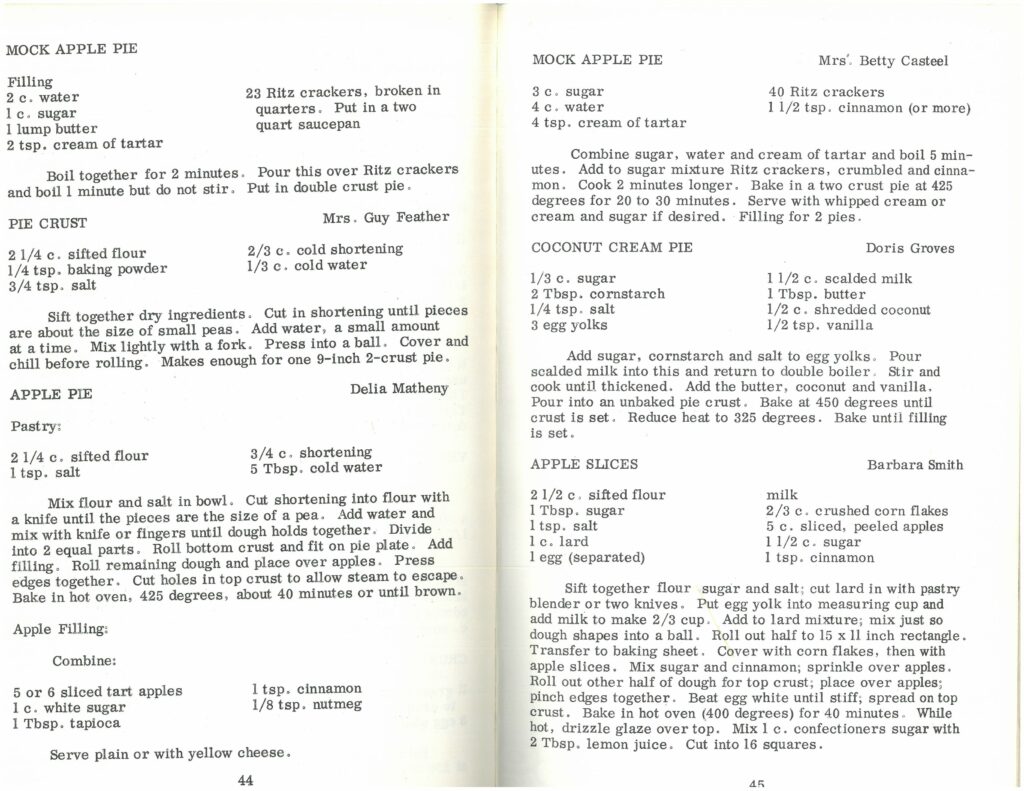

My friend loaned me Running on Red Dog Road. I put it in my “to read” pile and left it there since I thought it was probably another vanity press title. I had seen red dog roads, created by reusing coal mining slate, when I visited McDowell County in the 1970s, so after the book sat in that pile for years, I finally read it. As I began to read, I discovered that the little memoir of life in 1940’s Beckley was a very pleasant surprise. Ms. Berkheimer captured the life of a young girl in southern West Virginia with such detail that I was transported back to my own childhood. I could almost taste the foods my mother made, including thick crust blackberry cobblers, stewed tomatoes, leather britches, and peas with pearl onions. I remembered stories of hobos coming to Mom’s door for food. I remembered long church services and tent meetings on hot summer nights. I remembered playing freely and falling into the stories people liked to tell. The one about her aunt’s experience with a lonely-hearts club was laugh out loud funny. Berkheimer recounts these stories with not only humor for the lightness of life but with compassion for the hardness of life.

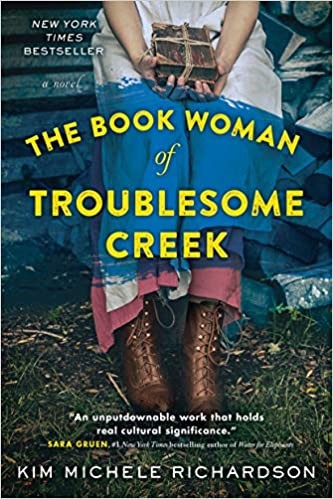

The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson. 2019

Richardson deals with two fascinating topics in her recent popular novel. The “book woman,” Cussy Carter, is based on the New Deal circuit-riding librarians of Kentucky, part of the Pack Horse Library Project. Cussy is also one of the genetically altered blue-skinned people of Kentucky. Two themes emerge then: the power of reading and education for escapism as well as practical information; and the bigotry and isolation faced by someone who looks different. As Cussy travels her route on her mule over rough terrain, she meets and befriends a cast of characters, mostly poor and struggling. They are the women, men, and children of the isolated Kentucky mountains. Poverty, class, and hunger are other prevalent themes in this Depression era engaging novel.