Collecting Easter Postcards

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.March 29th, 2021

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Associate Curator for WV Books & Printed Resources & Rare Book Librarian

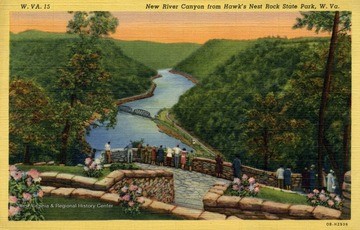

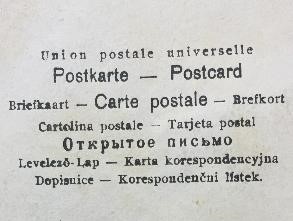

Postcards, a popular form of communication particularly in the late 19th and early 20th century, were sent to friends and family for all occasions. Mail delivery was reliable, running twice a day in most communities, and cheap, since postage stamps were only a penny. With the availability of twice daily delivery, postcards were nearly as quick as a telephone call, another late 19th century invention, and almost as fast as an email sent to your inbox today.

I’ve collected postcards for many years. I’ve purchased postcards from places I’ve lived, places I’ve visited, cards celebrating birthdays, and congratulatory cards filled with best wishes for their intended recipient, but my favorite collecting category is holiday postcards.

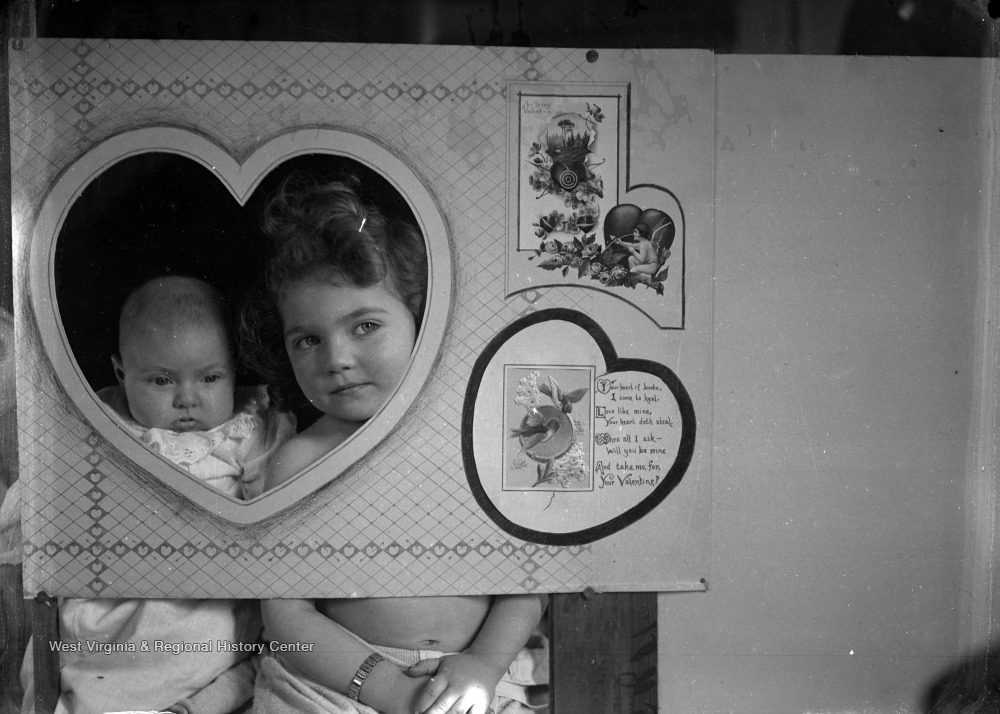

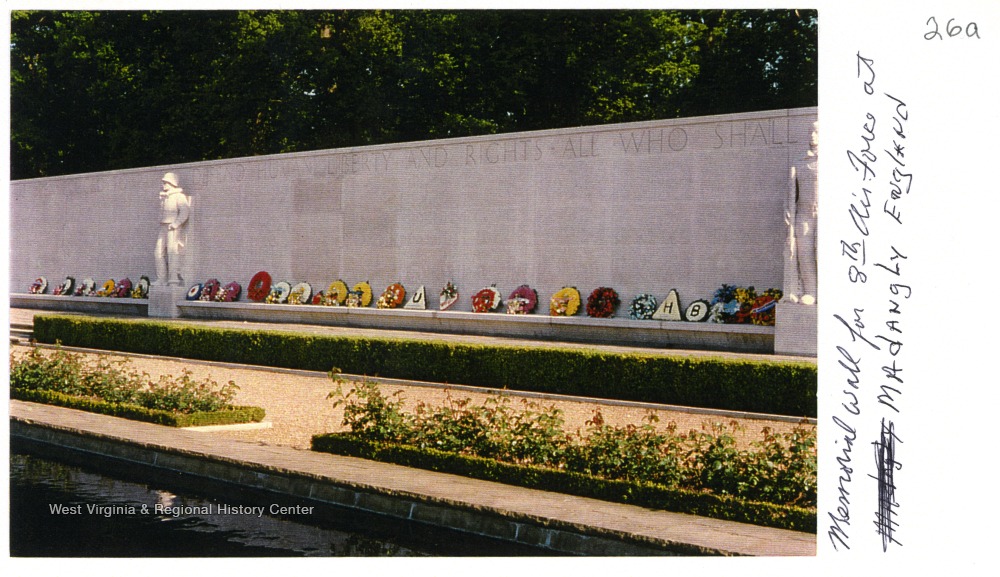

It’s easy to find them. I’ve collected hundreds of Christmas postcards over the years. I’m also fond of cards depicting New Year’s Day, though they’re harder to find. It’s very difficult to find Valentine’s, Memorial Day, George Washington’s birthday, or Thanksgiving postcards. My collection includes only a couple of each of these cards.

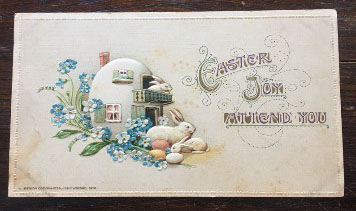

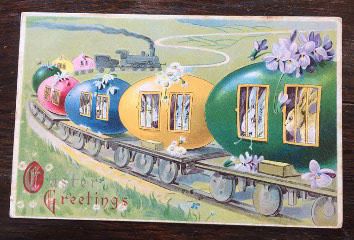

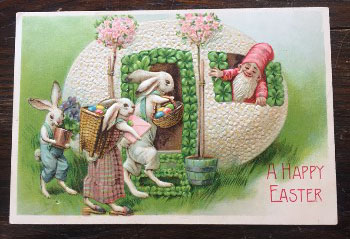

Easter postcards are my favorite collecting category. Besides the traditional bunnies, eggs, and chicks there are many unusual cards that we might not think of today as being associated with Easter. My collection also includes many religious Easter cards, but today, I’m going to share with you some of my favorite cards featuring all the cute things you’d expect to find in your Easter basket.

If you collect cards for a while, you’ll find that they can be organized by theme. Eggs are the central focus of these cards. These four postcards depict eggs as vehicles, such as the bunny train and the bunny drawn chick chariot. Others are used for housing, such as the egg with a balcony and the one made from flowers with a little gnome peeking out the window.

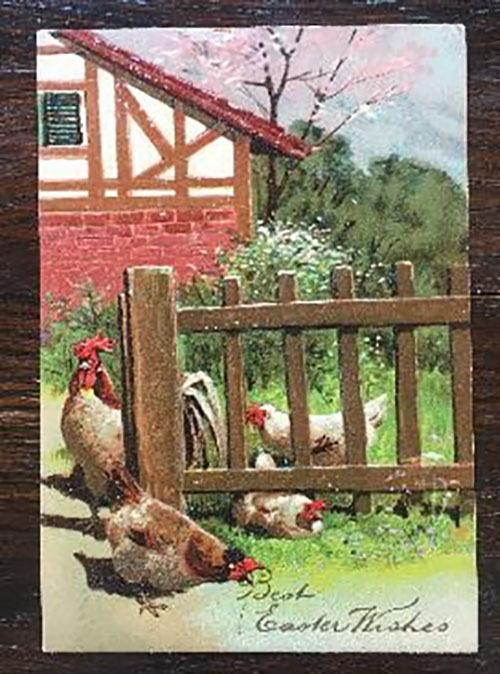

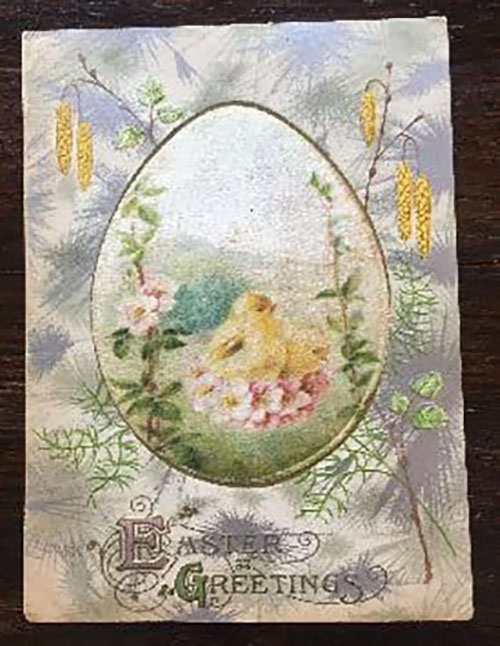

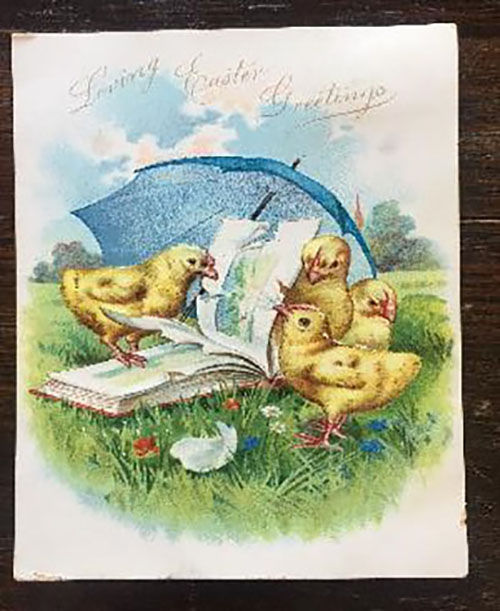

The postcards below have chickens or chicks for their central theme. Eggs are still an important focus for the chick cards. Notice these cards are all vertical in design, while the previous ones were all horizontal. The second card is interesting because it shows a chick and egg surrounded by natural greenery seen in spring. The yellow catkins dangling on each side are flowers from trees. These look like the catkins of the birch tree. The center egg is printed cloth with padding behind it. Even after 111 years, this card is dated 1910, it still creates a charming effect.

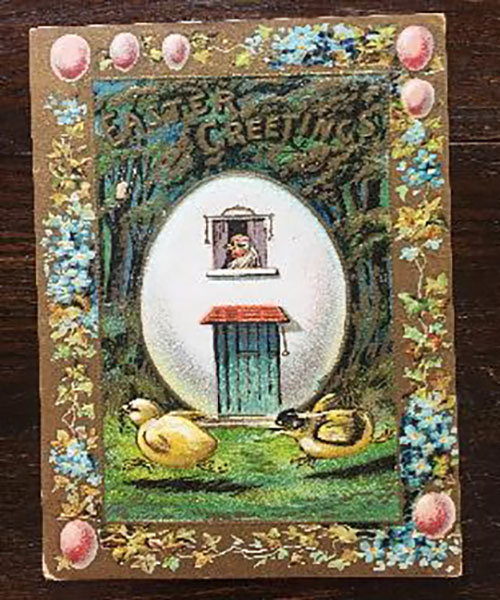

The hen house is one of my favorites. There’s the mother hen looking out her window, watching her chicks playing in the yard below. And what in the world are those chicks doing pecking at that book?

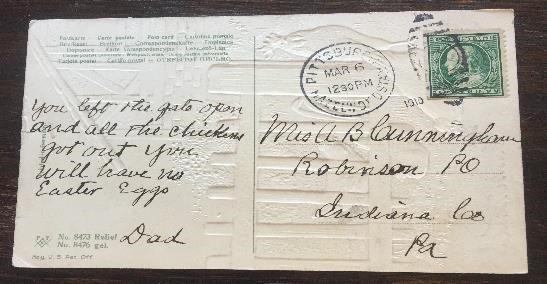

Messages on the back of the postcards are another reason to collect them. Letters home from World War I soldiers, cards posted to friends and family, love notes to a significant other, are all common. Then there’s a message like this one, written on the back of the card above, showing a flock of chickens by a gate. It’s a humorous note from a father to his daughter:

“You left the gate open and all the chickens got out. You will have no Easter eggs.”

Dad

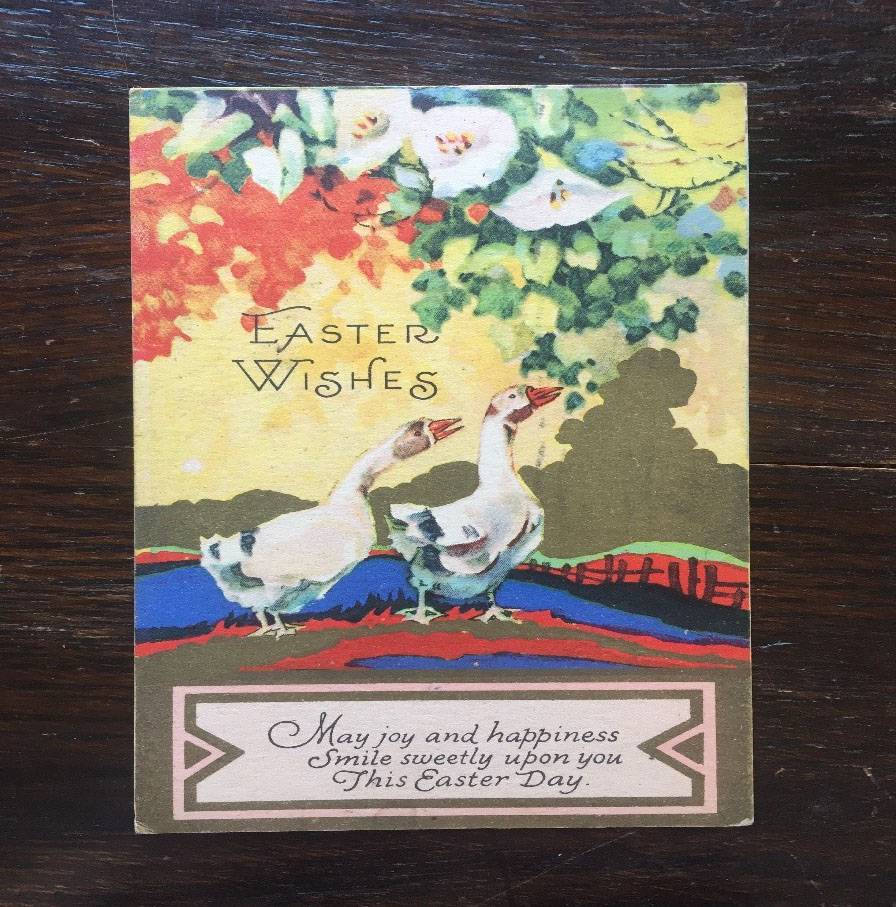

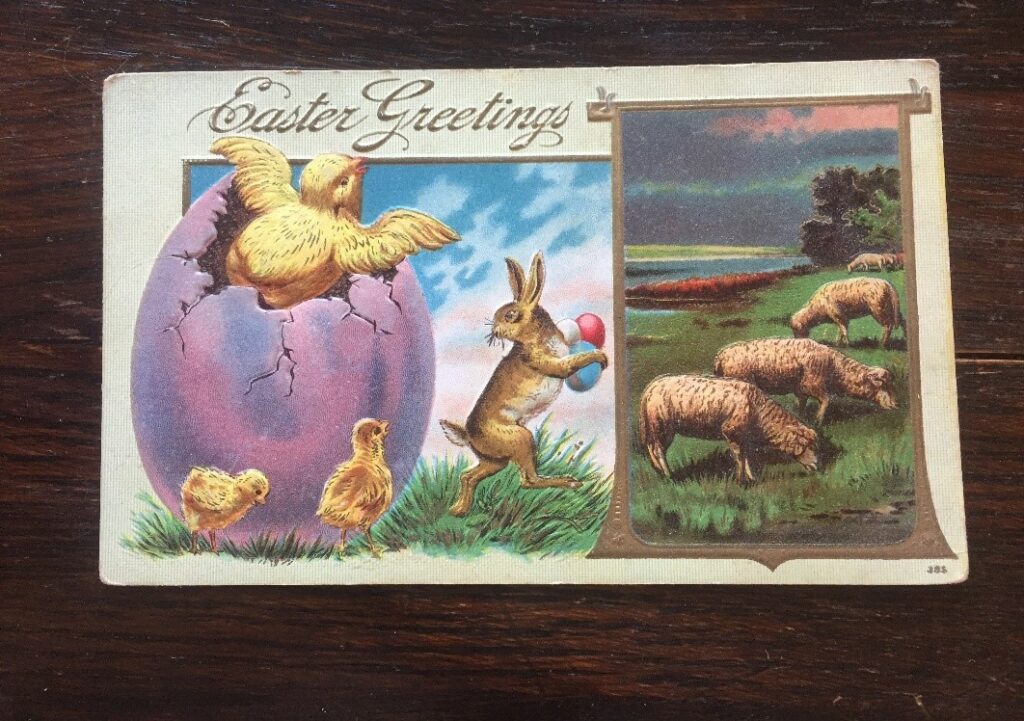

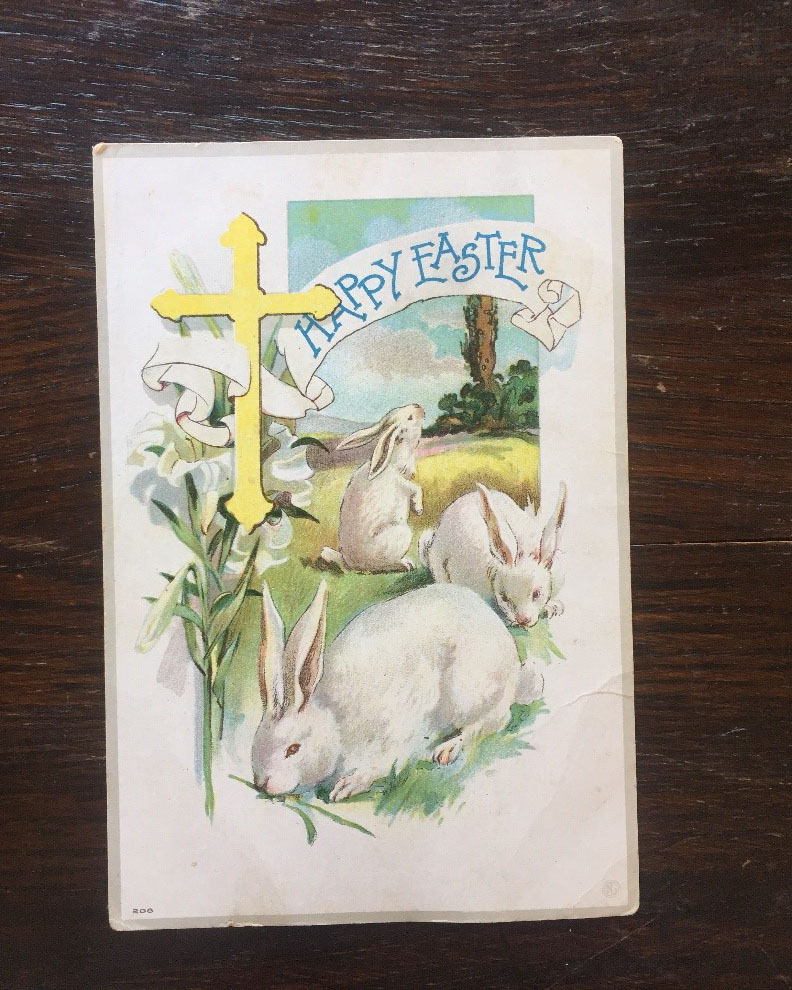

Other animals that may not come to mind as associated with the holiday made appearances on Easter cards too. The geese, sheep, and kittens pictured here make for nontraditional Easter cards. The goose was printed later than the others in this collection. It was printed in 1931 in the Art Deco style, showing that Easter postcards remained popular.

Two of the cards combine both secular and religious aspects of the holiday. The sheep grazing in green pastures is reminiscent of the 23rd psalm, but the opposite panel shows all the traditional secular symbols of chicks, eggs and bunnies. The combination of bunnies with a cross over a spray of Easter lilies also brings together these two categories. These are unusual, as least in my collection, as cards are either specifically religious or secular in theme.

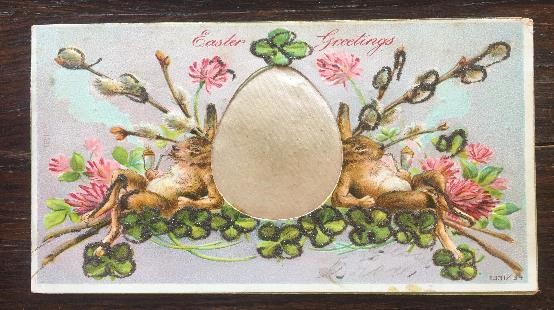

If the delivery of Easter baskets were left up to these two lazy bunnies, pictured below, no one would wake up to treats or have fun at an Easter Egg hunt. This is an undated European card according to the information on the back. There’s lots of interesting details that draw your attention in this card. Like the catkin card above, the center egg is cloth and it has been padded underneath so that it will stand out from the card. The surrounding shamrocks and pussy willow buds are edged in glitter with a dash or two of glitter on the pink clover.

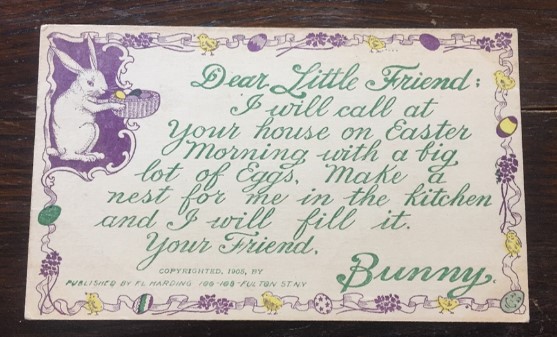

But never fear, the real Easter bunny, pictured below, is here and he’s going to make sure all the little children receive their Easter baskets. This card, bordered with ribbons, eggs, chicks and flowers, copyrighted in 1905, borrows from the cookies and milk usually left out for Santa. Here, the Easter bunny asks children to make a nest for him in the kitchen so that he can fill it with eggs – chocolate ones of course! He’s pictured here with a nest and eggs in his paws to prove it!

Dear Little Friend,

I will call at your house on Easter morning with a big lot of Eggs. Make a nest for me in the kitchen and I will fill it.

Your friend,

Bunny

If you’d like to see more vintage postcards there are several available in the archives at the West Virginia and Regional History Center. If you’d like to see more of my personal postcard collection, request A&M 3989, to see an antique postcard album filled with cards spanning various holidays.

Happy Easter!