A Woman’s Book: How to Know the Ferns, A Guide to the Names, Haunts, and Habits of Our Common Ferns, by Frances Theodora Parsons

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.January 4th, 2021

Blog post by Stewart Plein, Associate Curator for WV Books & Printed Resources & Rare Book Librarian

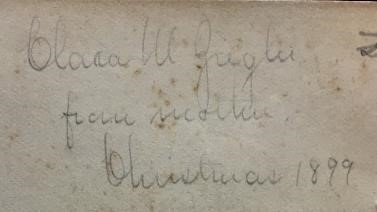

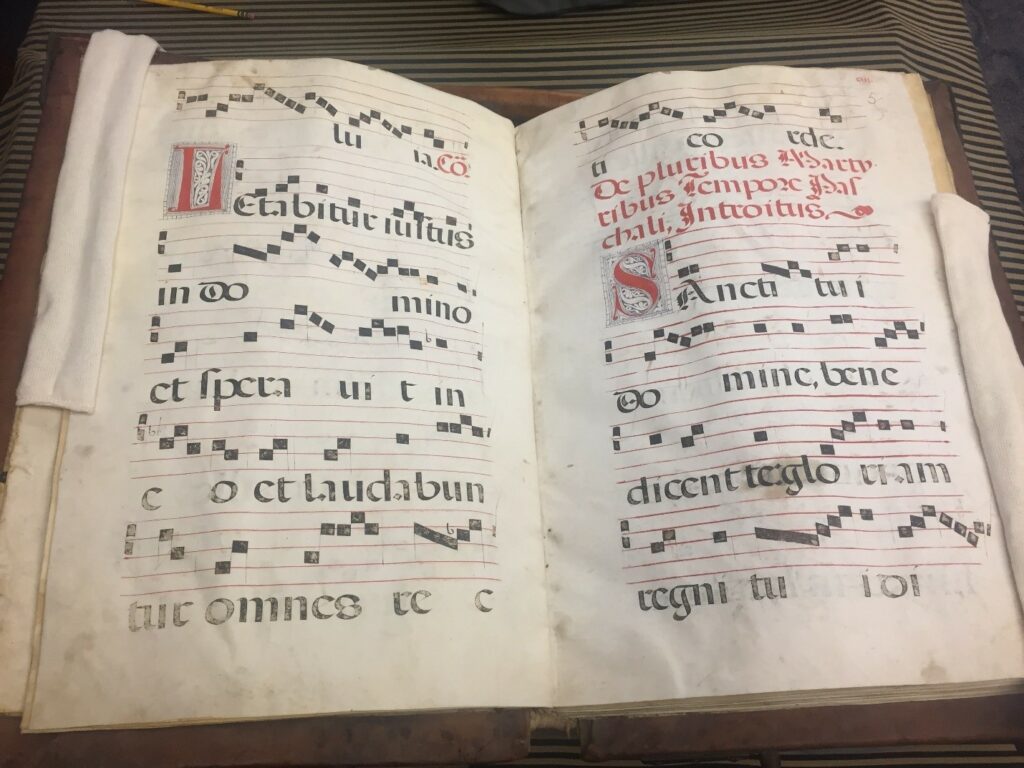

In 1899, Clara W. Greglee or perhaps Griglee, received this book, How to Know the Ferns, as a Christmas gift from her mother. Although there is little that we know about Clara, including the correct spelling of her surname, we do know that she was a passionate amateur botanist. We know, because her book is stuffed with the ferns she picked, pressed between the pages, and identified in her book.

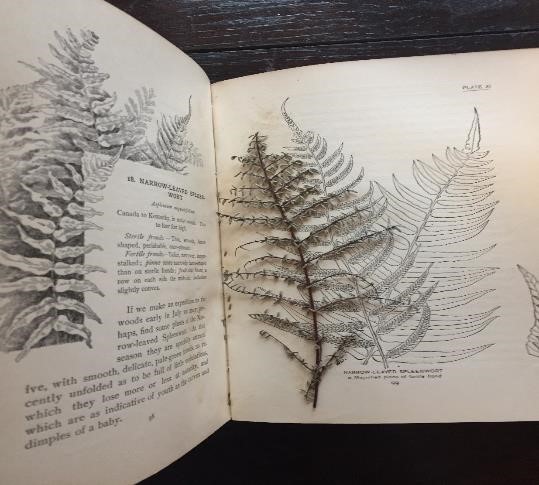

Above, we can see that Clara pressed a fern between the pages describing the Narrow Leaved Spleenwort. However, from her pressing, one can see that this particular example is not the Narrow Leaved Spleenwort, but another type of fern altogether. Perhaps, on this day, Clara picked and pressed as she walked, planning to identify the ferns she gathered at a later time.

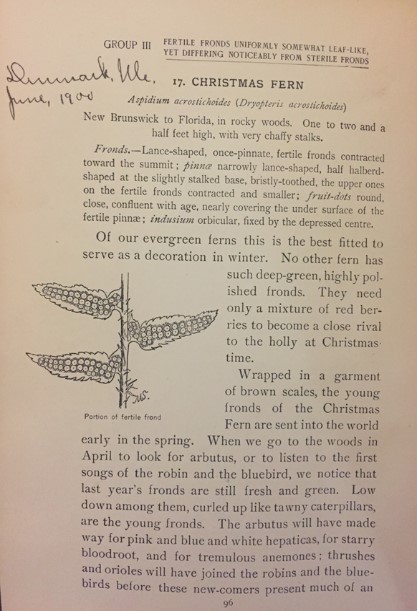

Clara also made notes in the margins of the guide book, such as the note in the photo above. According to this brief notation, we know that Clara identified one of the most common ferns, the Christmas fern, while in Denmark, Maine, in June 1900. This common fern grows all over the eastern seaboard, from New Brunswick all the way to Florida.

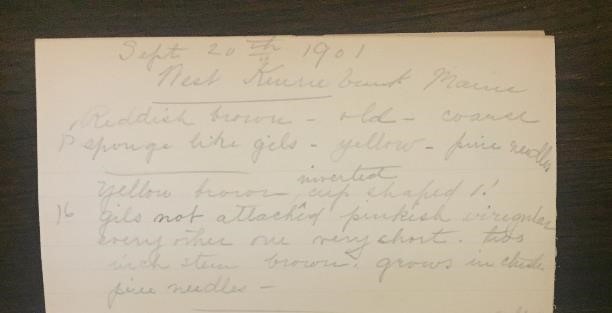

Ferns weren’t the only thing Clara hoped to identify. Pages of notes can also be found inside her book, slipped inside the front cover. On September 20th, 1901, Clara was identifying plants near Kennebunk, Maine. The first entry, perhaps a mushroom, reads “reddish brown – old – coarse sponge like gils.”

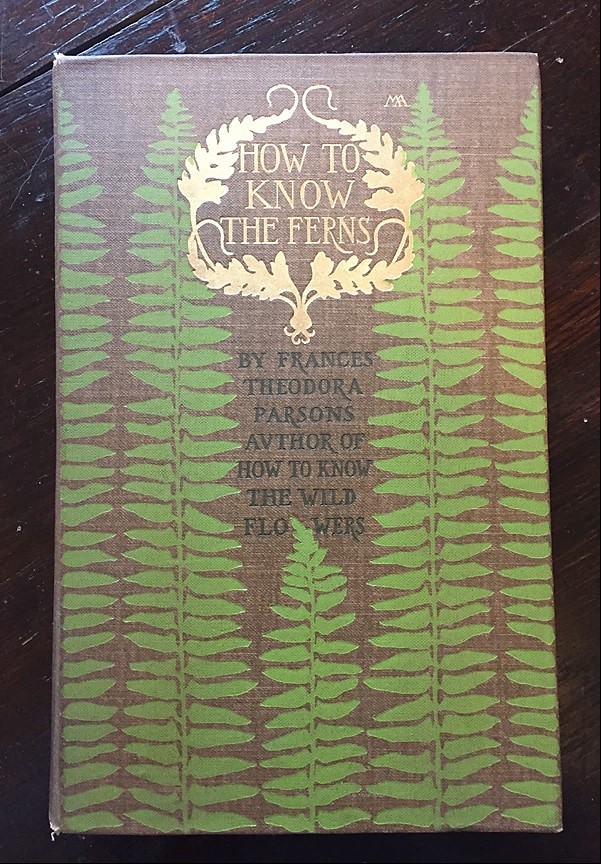

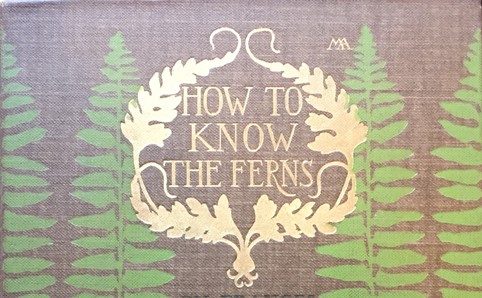

Clara was given this book in the first year of publication, 1899, and by observing the traces she left behind, we know that she was still using it to identify plants in 1901. But Clara wasn’t the only woman to be involved with this book. Three other women made this book possible: the author, Frances Theodora Parsons, the illustrator, Marion Satterlee, and the book cover designer, Margaret Armstrong. All three women were botanists.

The author, Frances Theodora Parsons, also wrote under her married name, Mrs. William Starr Dana. Following her husband’s death in 1890 during a flu epidemic, Mrs. Dana sought solace in nature. She took long walks with her friend Marion Satterlee, an artist. Together, Marion and Frances began identifying wildflowers. These long nature walks led to her first book, How to Know the Wildflowers in 1893. She would go on to publish two more nature guides, According to Season, 1894, and Plants and Their Children, 1896.

It was not until after Frances married James Russell Parsons, a politician and diplomat, that she wrote this book, How to Know the Ferns, which she considered a sequel to her first book, How to Know the Wildflowers.

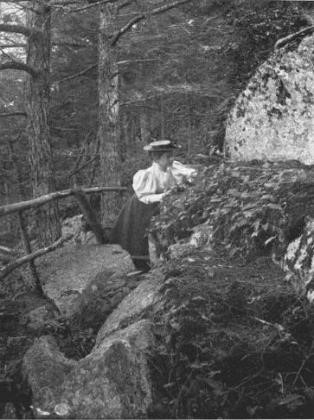

Her friend, and companion for the many long woodland walks together, Marion Satterlee, pictured below, would illustrate all of Mrs. Parsons’ books. She too, was a botanist and her black and white line illustrations beautifully and accurately depict the ferns they encountered.

A second artist, Alice Josephine Smith, also drew some of the fern illustrations. Unfortunately, no information could be found about her work or life.

The fourth woman to be involved with the making of this book was Margaret Armstrong, another artist/botanist who would go on to author and illustrate her own guide to western wildflowers, a guide that did not exist until she tackled it.

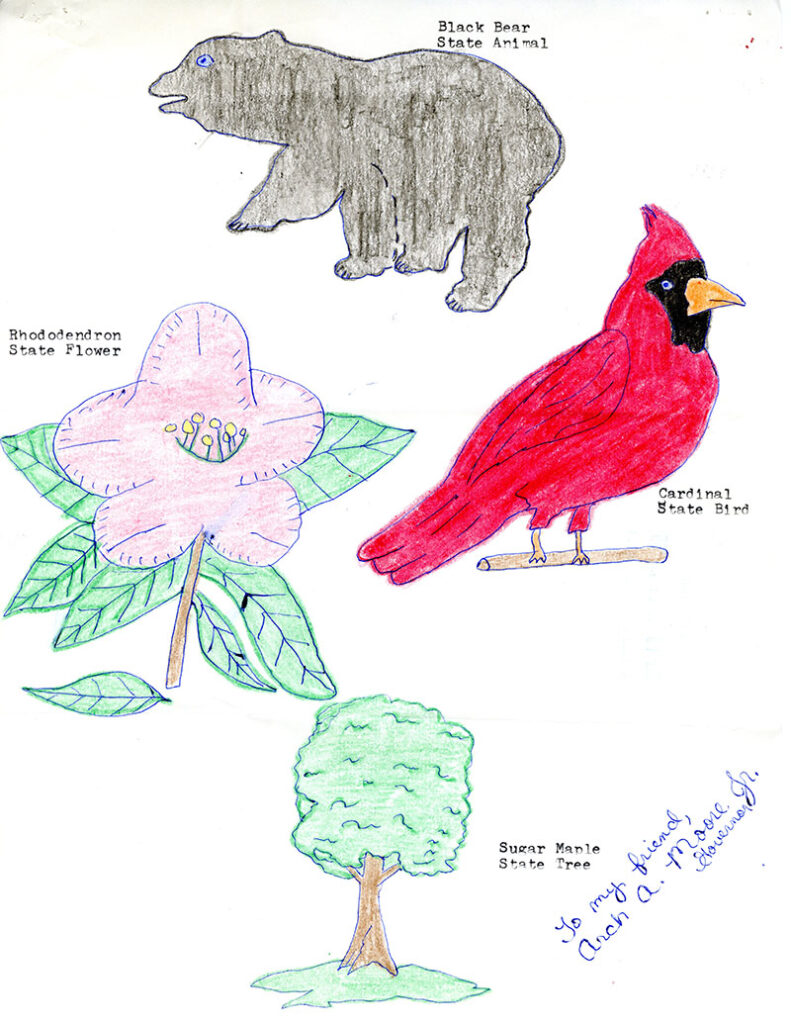

Armstrong, pictured below, was a well-known book cover designer. She created the designs that would be stamped in colored inks and real gold to make attractive book covers that would draw customers and increase sales. She chose to frame the titles surrounded by ferns, and she placed ferns across the cover stamped in green, as if they were growing naturally in the wild. She often signed her designs with a monogram, her initials MA, which can be found near the title at the upper right of the book.

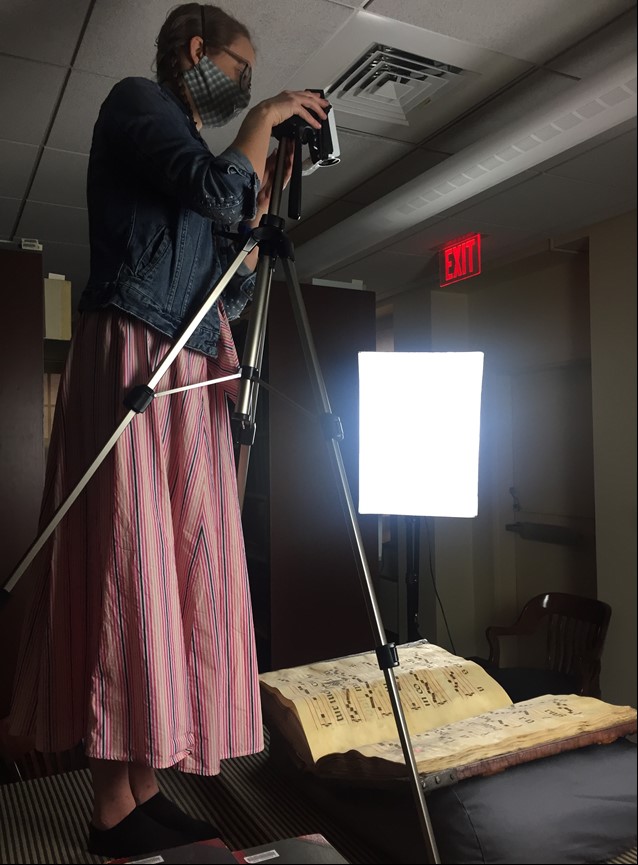

Taken all together, this is a book by women for women. Botany and plant identification were popular pursuits in the late 19th and early 20th century. It was a hobby women could enjoy, as seen here in this photo, pictured below, from the book. Seeing this photograph, we can picture Clara carrying her book with her into the woods, stopping to pick a fern and press it between the pages. We can see Frances and Marion, two friends who found companionship and the inspiration to create a book that would be enjoyed by others, and we can see Margaret Armstrong, another artist who could use her skills to make the book attractive enough to appeal to a mother as a Christmas gift for her daughter.

The rare book room in the West Virginia and Regional History Center has books by Mrs. Parsons, books illustrated by Marion Satterlee, nature guides, and many books with covers designed by Margaret Armstrong.

Resources:

- Frances Theodora Parsons image: https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q4815074 American botanist (1861-1952). Mrs. William Starr Dana. WikiData

- Frontis illustration: Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43167/43167-h/43167-h.htm

- Margaret Armstrong image: The New York Society Library: https://www.nysoclib.org/events/book-beautiful-margaret-armstrong-her-bindings

- Marion Satterlee: https://peoplepill.com/people/marion-satterlee

- Information on Frances Theodora Parsons and Marion Satterlee: Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frances_Theodora_Parsons

![Running on Red Dog Road: And Other Perils of an Appalachian Childhood by [Drema Hall Berkheimer]](https://news.lib.wvu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/image-3.jpeg)