I’m still hungry (for racial justice).

Posted by Admin.October 11th, 2021

Blog post by Christina White, undergraduate researcher at WVU

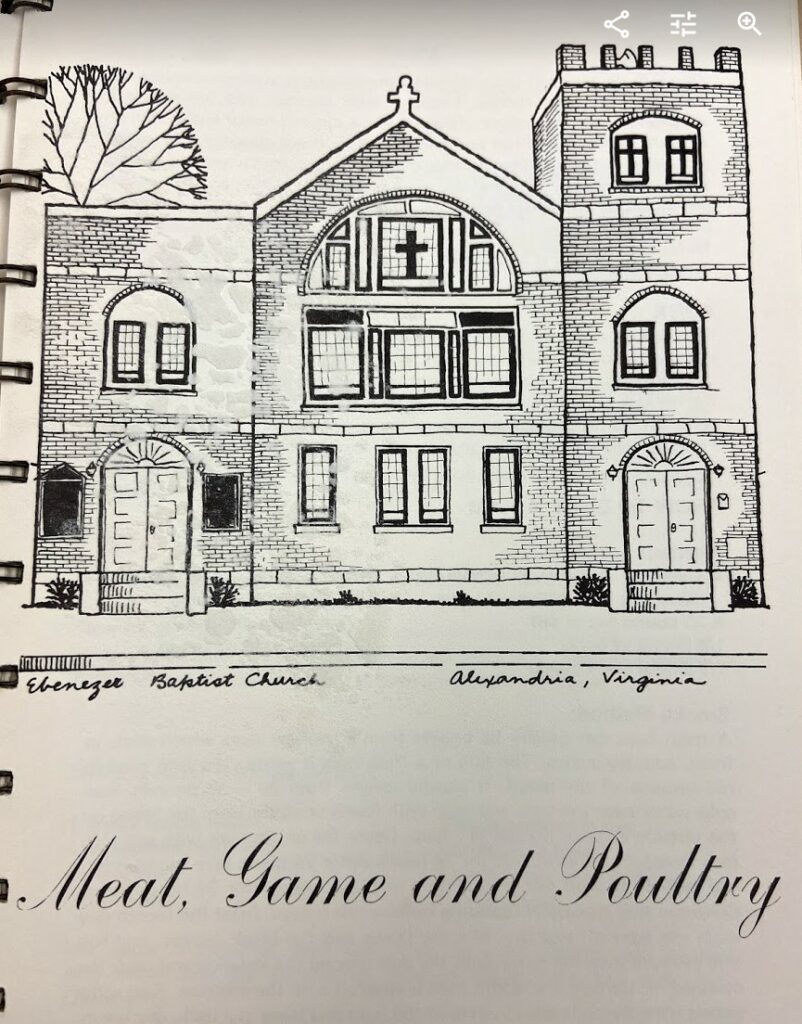

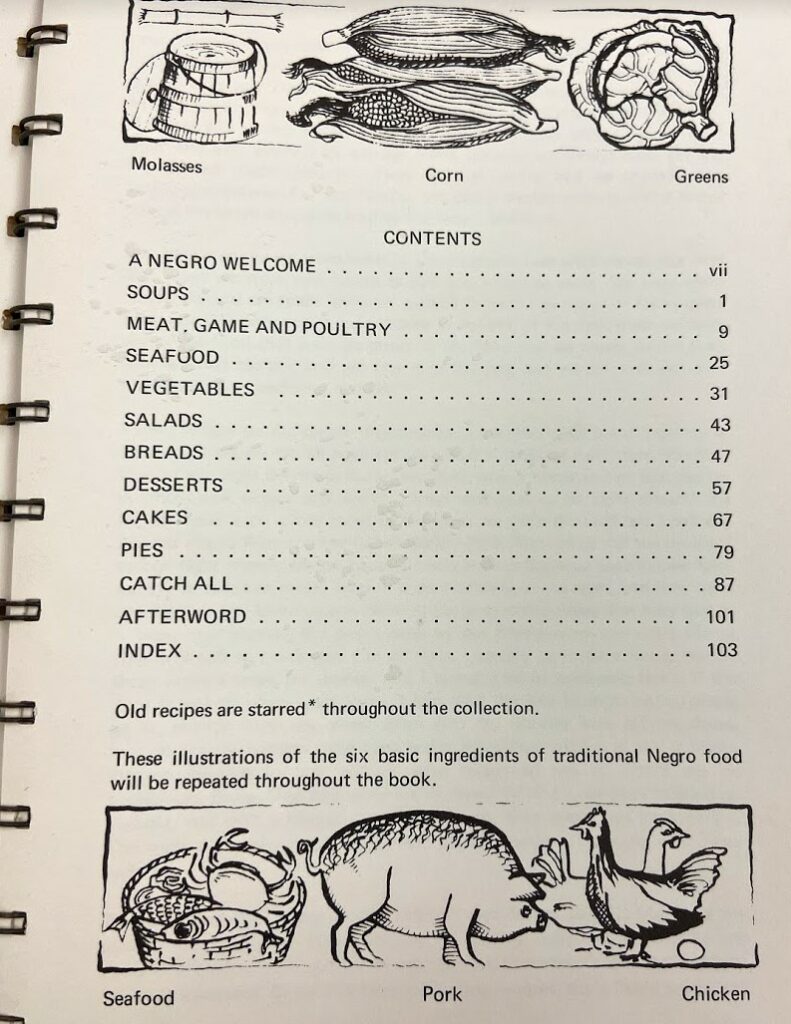

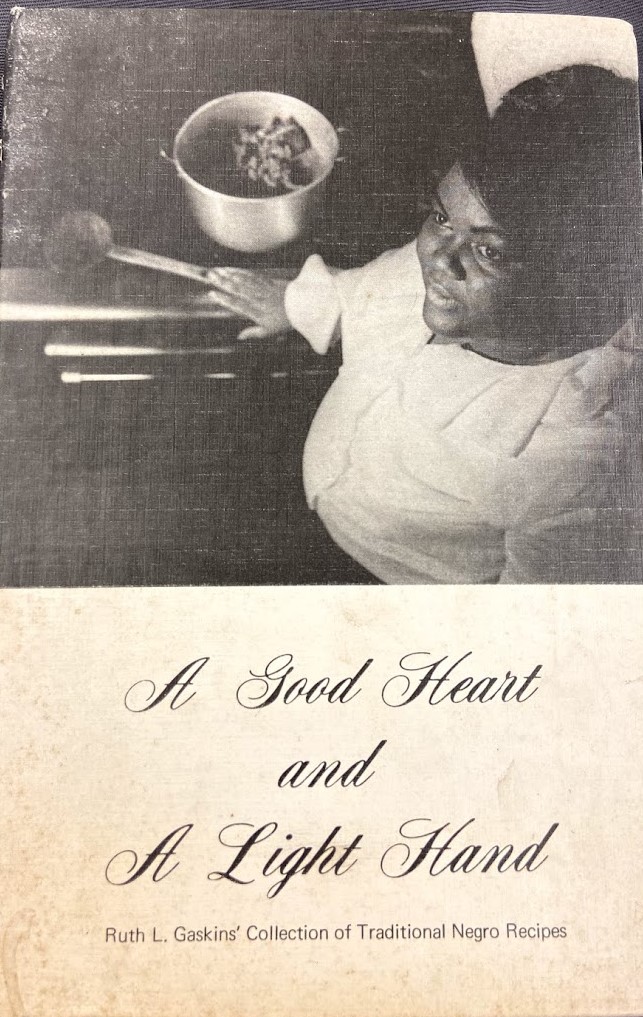

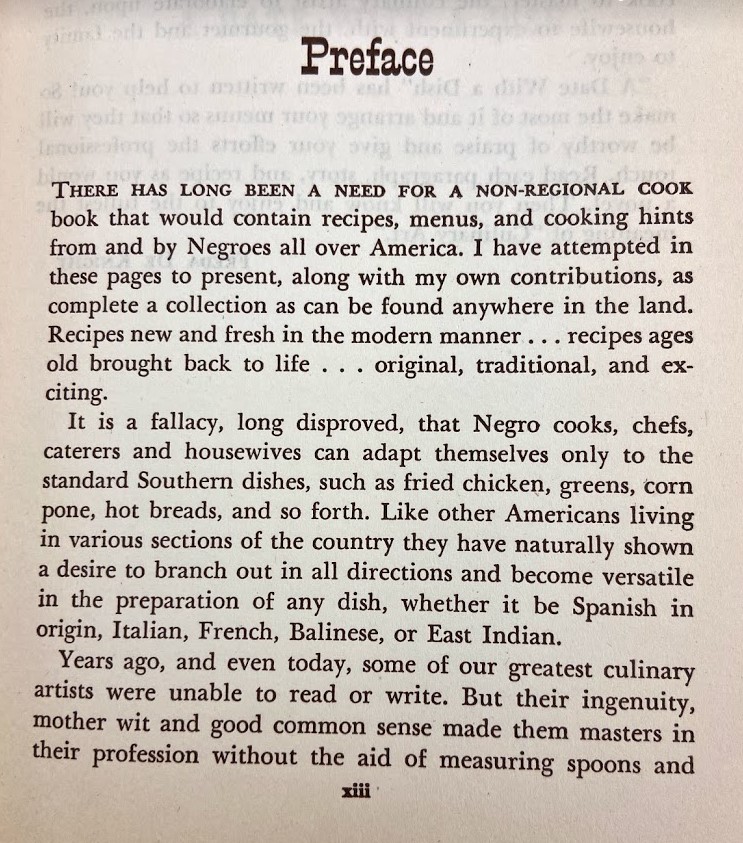

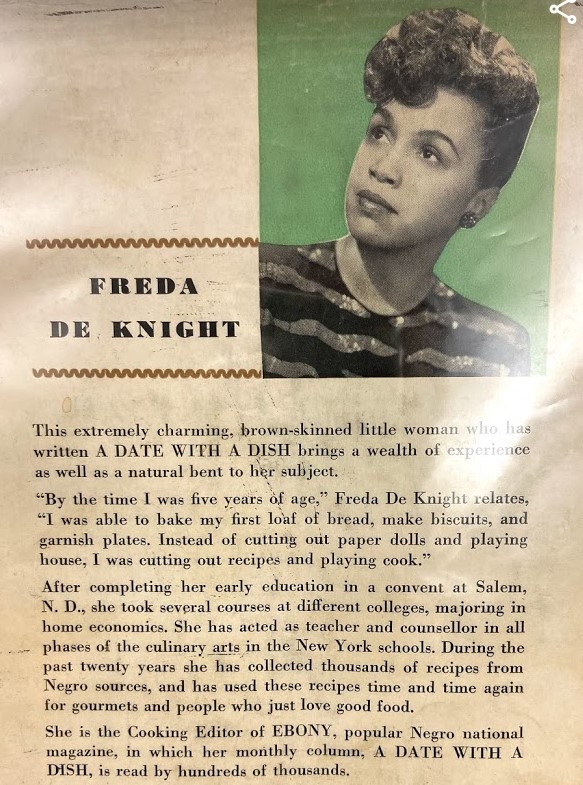

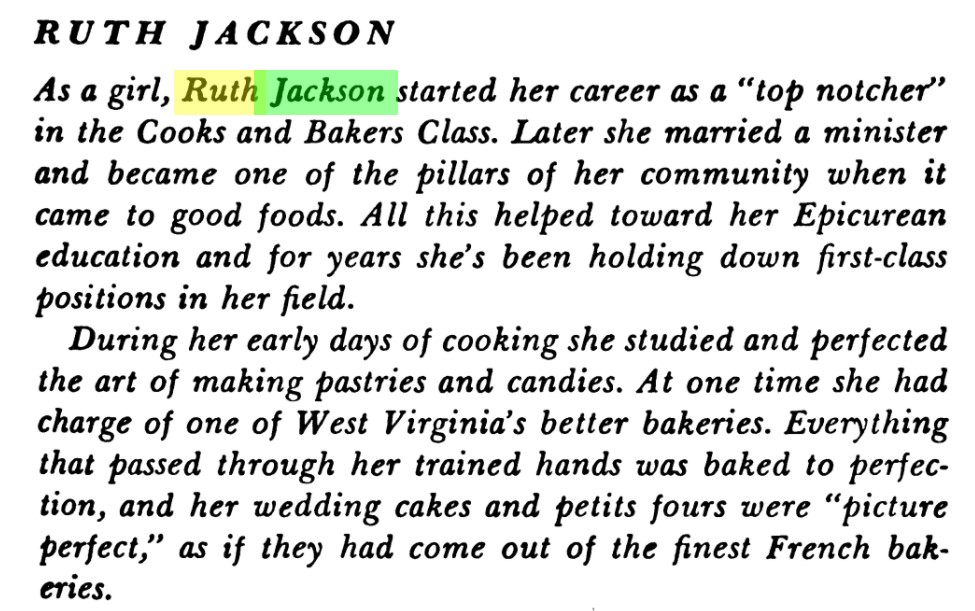

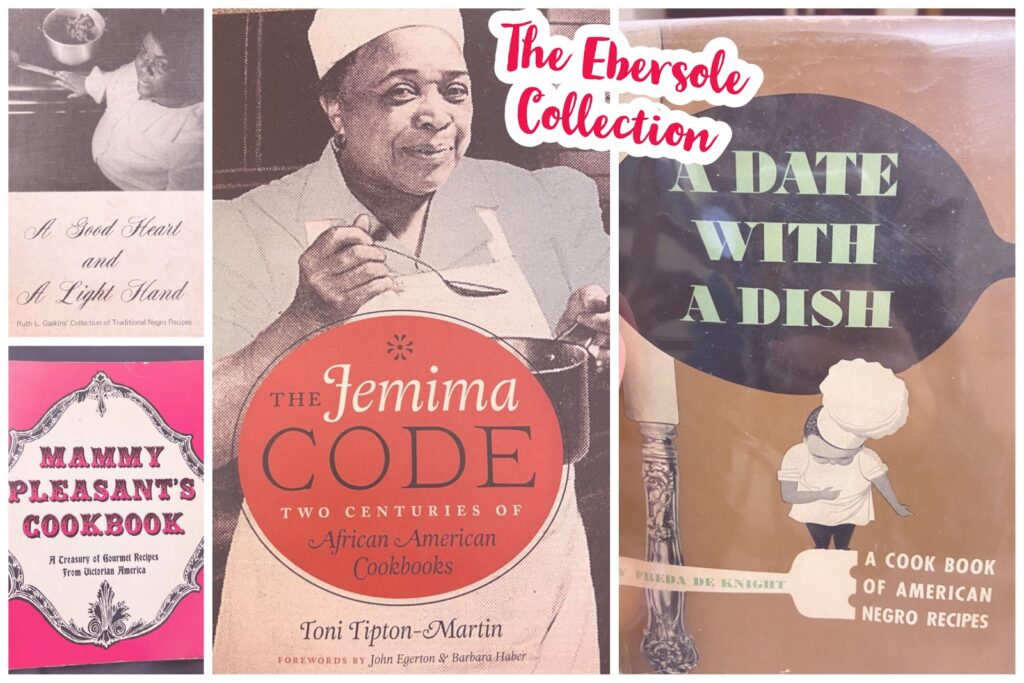

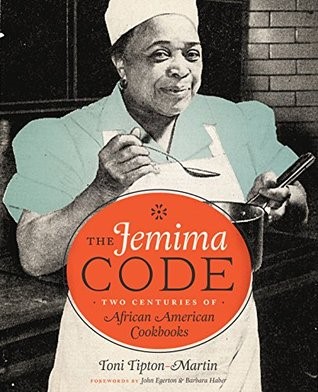

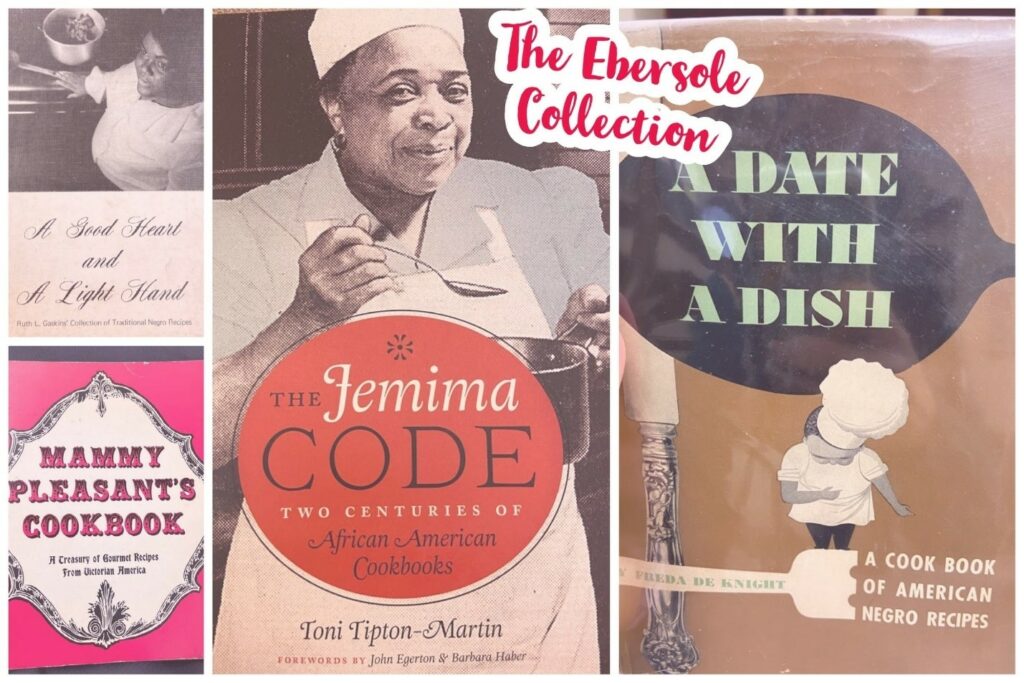

This is the sixteenth and final post in White’s series on race, justice, and social change through cookbooks, featuring the following books from the Ebersole collection: Mammy Pleasant’s Cookbook, A Date with a Dish, A Good Heart and a Light Hand, and The Jemima Code.

Writing a series of posts on cunning, determined Black women was an honor and a challenge. Half passion project and half professional goal, this blog is my mode of self-education and sharing lessons from cookbooks that you don’t have time to read.

Real talk: I grew up thinking it was rude to talk about race. Reflecting on this, I realize my good-intentioned parents probably felt uncomfortable or unprepared to educate their child about the oppression of Black Americans, or what my role would be when I grew up. My dad is from a small town in Appalachia where nearly everyone was white, and my mom hails from a different country where race issues appeared differently from those in the US. Either way, I needed to spark a discussion, beginning with myself, or else my comfortable silence might solidify into an illusion that I see too often: race isn’t that big of a problem today.

Not true!

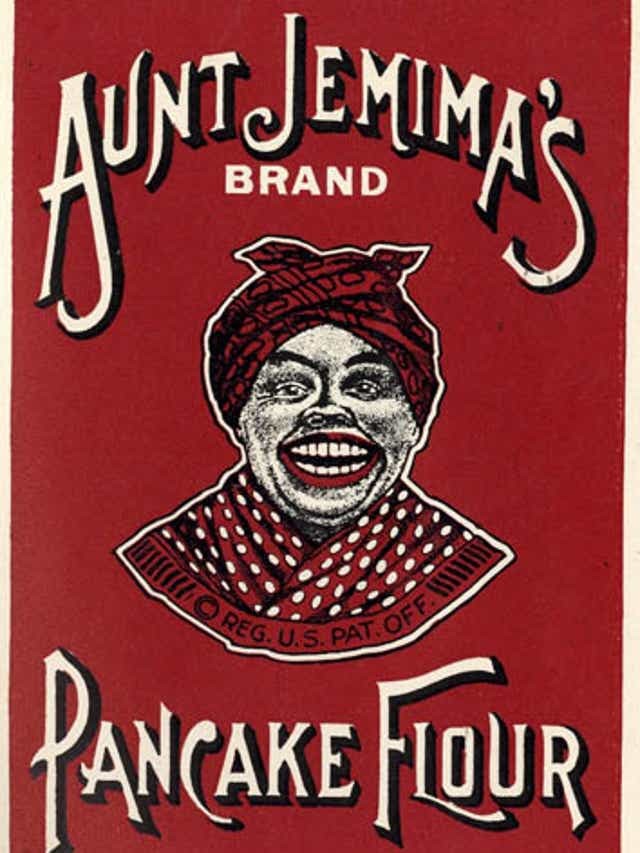

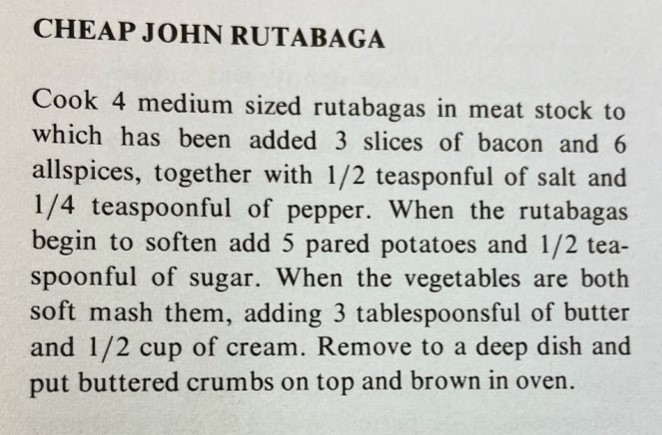

Each cookbook I wrote about in this blog introduced me to historical forms of marginalization, from mammy stereotypes to restricted access to culinary school. These methods roll into modern times under new names and symbols including Aunt Jemima syrup, a lack of representation in the cookbook scene, and the myth that Black food is unhealthy and greasy.

Writing these posts, I felt uncomfortable at times. I admit it — I walked into the Rare Book Room at the Downtown Library expecting a familiar lesson on slavery and Jim Crow laws, except focused on cooking. That’s not what I got! I was smacked in the face with racist tendencies that linger. Like I said, it wasn’t until 2020 that Aunt Jemima was rebranded and the mammy character was removed from syrup bottles at convenience stores and “socially-conscious” chains like Whole Foods.

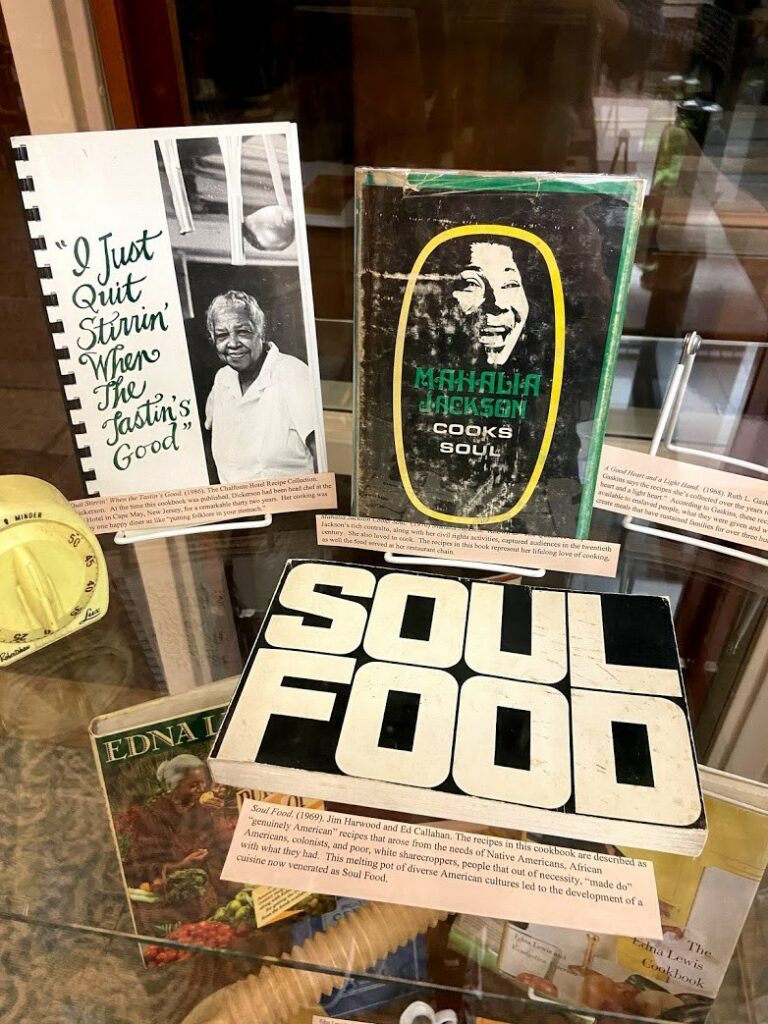

I reached into the Ebersole Collection with a goal to learn and share, and I left room for you to jump in. With hundreds of cookbooks, there are a million topics to tear apart. From race to mental health, single parenthood, international holiday traditions, indigenous peoples, environmentalism, and comedy, you’ll find something tasty and stimulating for a research project or class presentation.

The librarians are eager to help you! I wouldn’t have found my starting place without the hard work and generosity of Stewart Plein, the Rare Book Curator at the West Virginia & Regional History Center.

Some ideas: complete an Honors project using these primary sources, make a presentation, or revitalize hundred-year-old recipes. When you read something that moves or angers you, pursue that theme to its fullest. Chances are you’ll help yourself and others dissolve a stigma, myth, or prejudice that holds our society back.

Thank you, from the bottom of my stomach, for accompanying me on this journey. And if you have no idea what I’m talking about, start by going back to post 1! I hope I’ve inspired you to view food as a vehicle for social change, to get to the root of discomfort, and to give something new a try, whether it’s food or a different way of thinking.