Dr. Emory Kemp: The Book Collector

Posted by Jane Metters LaBarbara.July 27th, 2020

Blog post by Dr. Connie S. Evans, Ph.D., M.L.I.S., WVRHC AmeriCorps worker

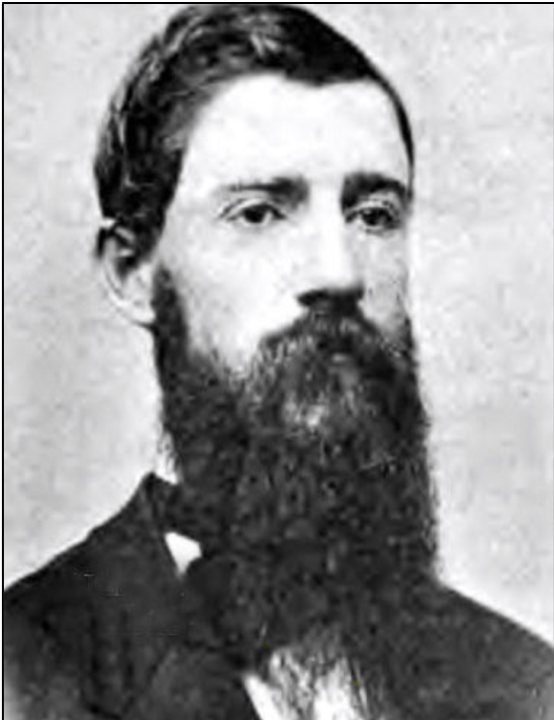

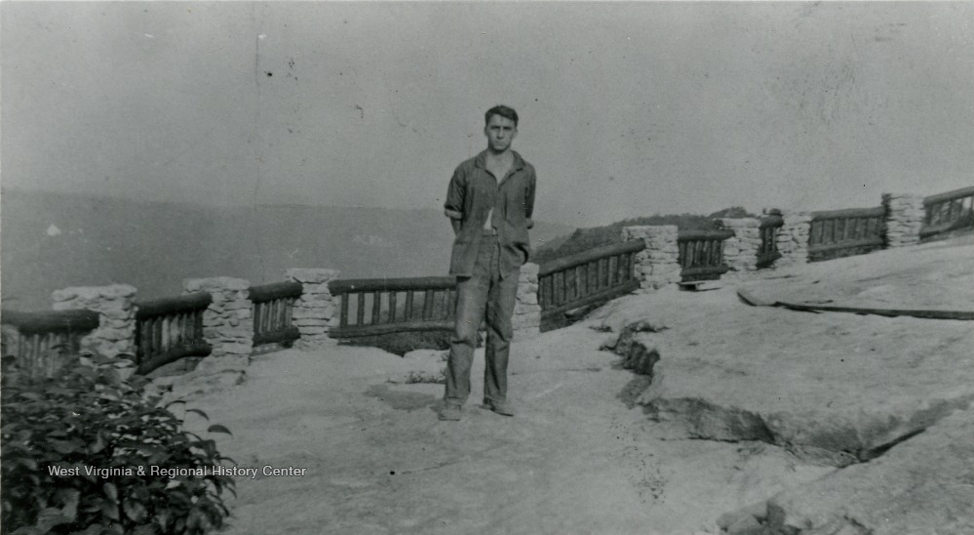

As many people are aware, Dr. Emory Kemp was an esteemed expert in the fields of civil engineering, industrial archaeology, and the history of technology, so it will come as no surprise that he was also an avid collector of books on a wide variety of topics. In his oral interviews with Dr. Barb Howe, he discussed at length how he developed his collection from a very young age, and how the volumes he accrued help shape his future interests and endeavors.

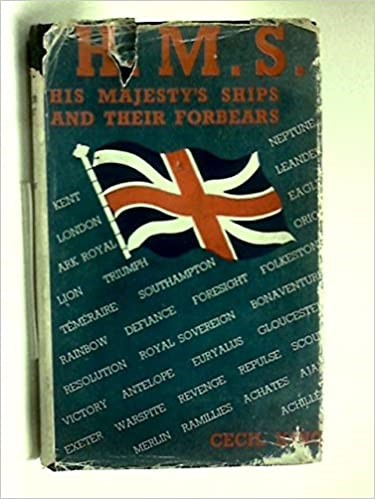

Born in 1931, Dr. Kemp made the decision to be baptized into the Methodist faith at the age of ten and noted that this event sparked his curiosity to study “many things.” As well, “the clouds of war were gathering…in Europe” in 1941, and Dr. Kemp became intrigued by the British Royal Navy and its ships, and, consequently, the general history of Britain. This interest led him to purchase his first book (which he retained throughout his life): H.M.S. His Majestie’s Ships and Their Forebears by Cecil King, which he ordered from the British Information Services in Rockefeller Plaza in New York City.

Dr. Kemp had already been following the fortunes of the war in Europe since 1939, and developed an interest in how the hostilities had evolved from the time of the German Weimar Republic and the rise of Adolf Hitler. He was also intrigued by the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s attempt to head off the conflict at the Munich Conference with his famous “Peace in Our Time” speech. From this interest sprang a desire to become more familiar with British history in general, and Dr. Kemp began collecting books in this genre as he was able to do so.

A precocious learner who had skipped a grade in primary school, Dr. Kemp entered a five-year program at University of Illinois Laboratory High School (otherwise known as Uni High) under the auspices of the University of Illinois in 1943 at the age of eleven; he went on to graduate from the school in 1948. While there, he became part of the school’s War Discussion Group which met once a week, and recalled that he “gave a couple of lectures on [his] understanding of the war itself,” no doubt as an outgrowth of his voracious reading on the subject. However, as Dr. Kemp self-deprecatingly noted, the lectures were never recorded so he was unable to quote from them.

As a young man, Dr. Kemp did not have a great deal of money at his disposal to purchase the books he wanted, and routinely devoted his weekly allowance and the sums he earned from babysitting his younger brother to their acquisition. His wish to buy more books for his collection led him to take a summer job at the Dick Burwash Farm near Champaign, Illinois, where he was hired to de-tassel corn.

The process of de-tasseling corn was aimed at increasing the production of hybrid corn, and it required stripping the tassels from corn by hand, in alternate rows, to prevent self-pollination. Dr. Kemp recalled that the work was difficult, as it was hot in the fields and the corn itself caused rashes on exposed skin. Both boys and girls were hired for the work, and paid equally, although, as Dr. Kemp ruefully noted, the girls were allowed to work from a platform attached to a tractor, while the boys walked the fields.

Dr. Kemp observed that he was never “very much interested in clothes or toys,” so he “haunted bookstores,” and purchased a variety of tomes with his summer earnings, many of which eventually found their way into the collection that he donated to the West Virginia and Regional History Center at the West Virginia University Libraries in October, 2016.

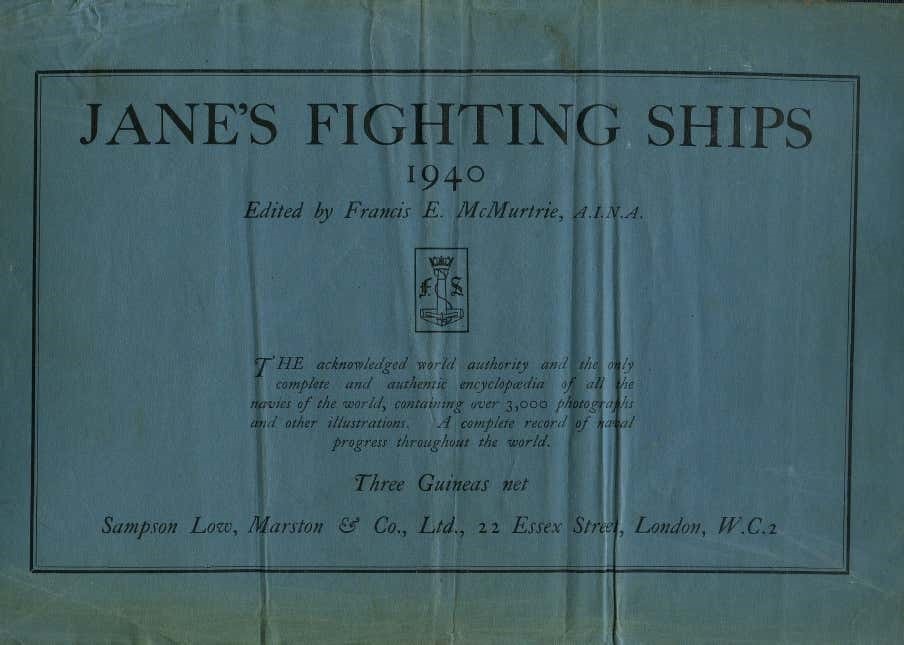

While a student at Uni High, Dr. Kemp met faculty members at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign who proved to be instrumental in the expansion of his book collection. Arthur Davis, an engineering professor, gave Dr. Kemp a number of books on the history of World War I; Dr. Davis, teasing Dr. Kemp, told him that, “I hope we never have war with Germany, because you’ll be incarcerated.” Christmas presents from Dr. Davis were often in the form of more books for Dr. Kemp’s collection. Indeed, his wife, Fern, gave Dr. Kemp one of his favorite books as a Christmas present: the annual edition of Jane’s Fighting Ships by Francis E. McMurtrie, which was a detailed listing of all of the British Navy’s military ships then on the line.

As a student at Uni High, Dr. Kemp was also afforded the use of a University of Illinois library card. Dr. Kemp stated that he “haunted” the university library, and “made very good use” of his library card, at a time when the free run of its stacks was very much an exceptional privilege. He was also able to avail himself of its Interlibrary Loan service in order to get access to materials not held in the library. Today, a corridor of the library contains a collection of bronze plaques that laud outstanding graduates of the university, and Dr. Kemp proudly noted that his name can be found among that group.

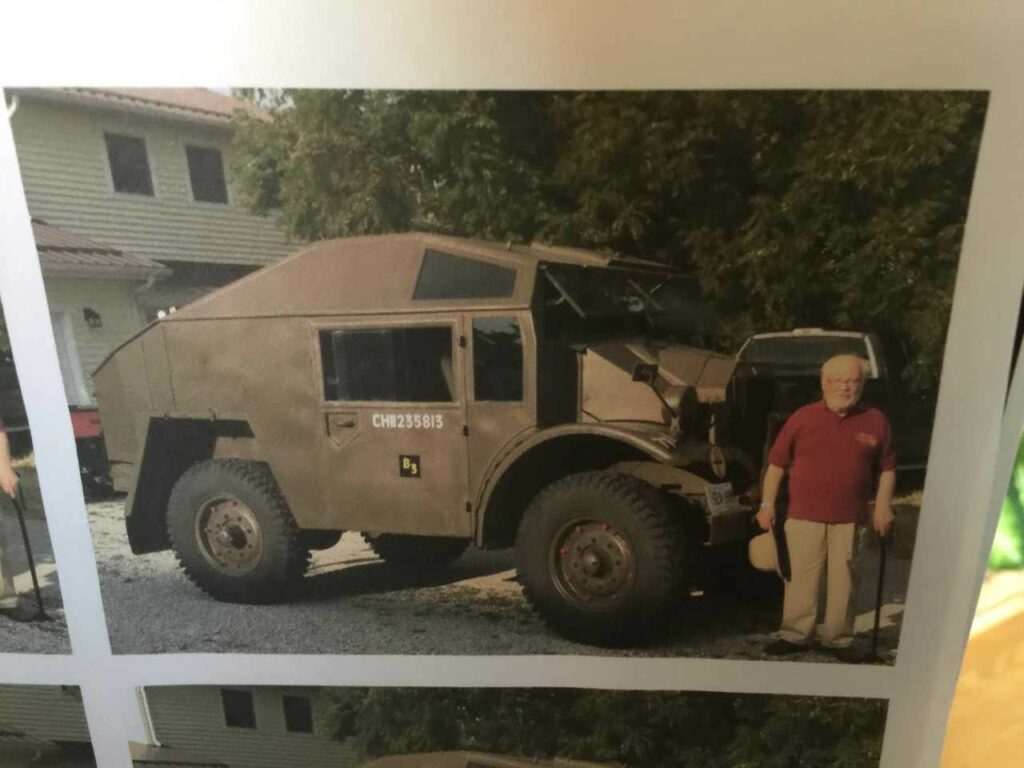

Through his interest in the war, and the Royal Navy in particular, Dr. Kemp drew inspiration from the drawings in Jane’s Fighting Ships to expand on an earlier hobby of constructing small-scale models from scratch; one of those was of the HMS King George V. His process was to make drawings, from which he then made the models, with an emphasis on the ships’ armaments. His collection eventually included military ships from the Royal Canadian Navy as well. Indeed, Dr. Kemp gleefully recalled that, on a recent visit to Canada, he had been able to ride in a British Army artillery tractor, and had promptly pulled out a model that he had made as a boy to “refurbish” upon his return home.

(photo courtesy of Dr. Janet Kemp)

Dr. Kemp’s interest in the British Royal Navy led him to explore its origins and development from Elizabethan times forward, as he believed that the Navy, as an instrument of state, had its beginnings in the late sixteenth century. His research revealed that the government began to build its own ships after the Glorious Revolution in 1688, when James II was forced to abdicate in favor of his daughter, Mary, and her husband, William of Orange. Dr. Kemp said that he began to get very interested in the details and strategy of the Royal Navy as the British Empire expanded; he was also subsequently drawn into Irish history by James II’s attempt there to regain his throne.

Dr. Kemp also read widely about the history of the conflict in Northern Ireland due to his friendship with Fred McAdams, whose father had marched with the Orange Order (the Protestants). This group formed the basis of the Ulster Division (later the Ulster Volunteer Force), which would go on to fight in the First World War at the Battle of the Somme; Dr. Kemp noted that his research revealed that the division was almost wiped out in this one battle, thus decimating their geographic region at home. As a result, Dr. Kemp’s research in this subject came to shape some of his views of war and military engagement.

Moving on from history, Dr. Kemp also acquired a large collection of engineering and mathematics books, many of them in the area of the history of technology and, more narrowly, the development of the steam engine. He learned a great deal of technical information from Henry L. Dickenson’s A Short History of the Steam Engine, which is part of his donated collection. Dr. Kemp also read widely in the areas of thermodynamics, the manufacturing of textiles, British engineers working on harbors, and the British railway system. Dr. Kemp remarked that several of the textbooks he had used when he was a student at the University of Illinois were donated to the university, but that he retained five shelves of books on twentieth-century engineering. Dr. Kemp’s engineering and technology interests meant that he also acquired a number of books on mathematics, and he said that he has passed on several of these volumes to his grandson, Dr. Paul Anderson, also a civil engineer.

While Dr. Kemp was serving in the army during the Korean Conflict, he was assigned to the Engineering Research and Development Lab in Virginia. He began to take courses at George Washington University, where a class in differential equations with Dr. James Henry Taylor sparked a new interest—and a new area for book collecting—for him. Dr. Kemp playfully recalled that he had told a WVU provost that an educated person must have “a familiarity with calculus.”

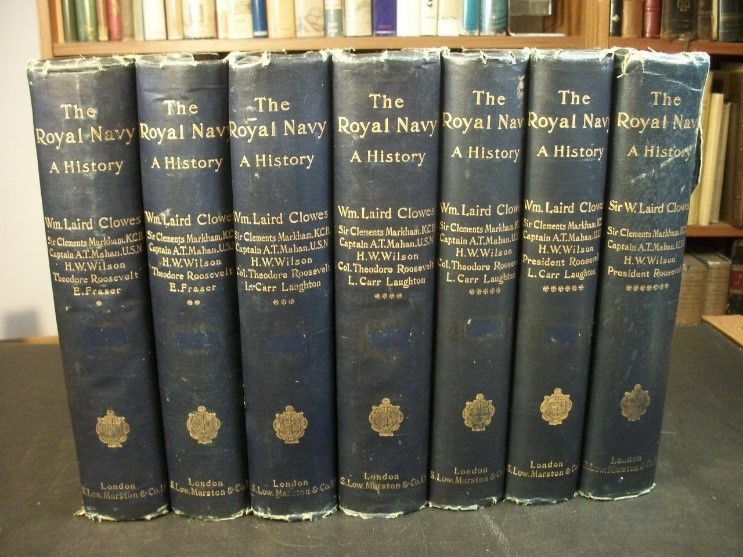

When Dr. Kemp received a Fulbright Fellowship to study in England in 1953, he shipped some of his books to England, but managed to acquire a significant number of volumes while he was there, thanks to a book allotment that was part of the scholarship grant. He was particularly partial to two bookstores in London: one that was in the South Kensington Underground station, and the other, more famous one, Foyle’s, in Charing Cross Road. Dr. Kemp said that the books he purchased at that time were inexpensive, and that he developed a relationship with the bookseller, who put him in contact with publishing houses so he could buy books at a discount. Through the bookseller, he was able to purchase the seven-volume set of The Royal Navy: A History – From Earliest Times to 1900. Dr. Kemp emphasized that establishing a good working relationship with a bookseller is one of the keys to the development of a good book collection.

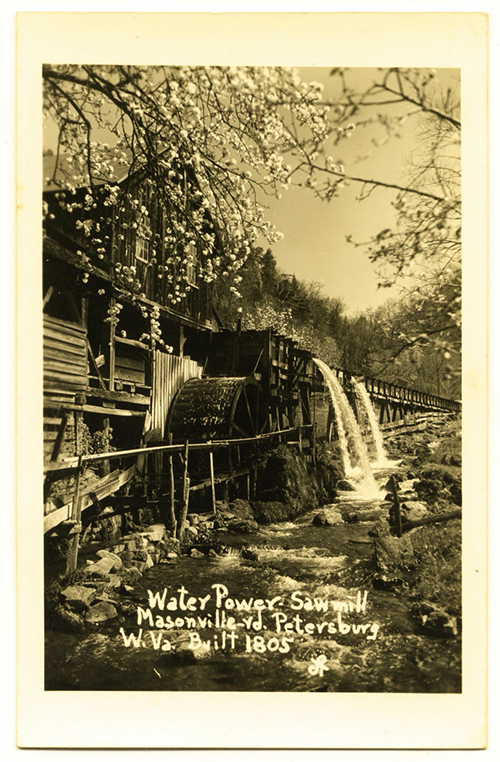

When the time came for his return to the United States, Dr. Kemp was faced with the somewhat herculean task of getting his books back home. He had taken a job at Ove Arup and Partners, one of the leading engineering firms in London, and was part of a team working on the Sydney Opera House. One of his friends in London, Felix Winkler, a refugee from Czechoslovakia, had shipped all of his belongings to London in big wooden crates he had made at a sawmill. Dr. Kemp took the empty crates and rebuilt them to accommodate his book collection and other belongings; he then shipped them to Chicago via Liverpool, where the emptied crates stood for “many years” in the parking lot of the complex in which he and his wife had their first apartment. Dr. Kemp recalled that they were eventually broken up for firewood, but stated, “I regret not keeping those things.”

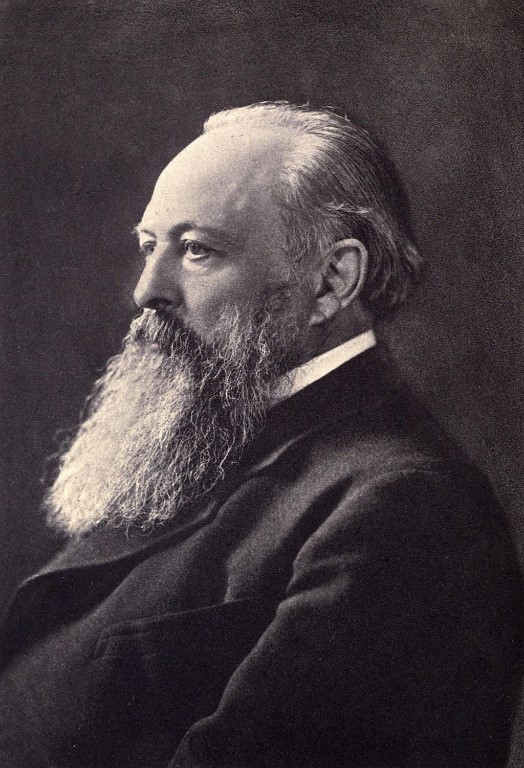

Among Dr. Kemp’s favorite volumes was the series of The Cambridge Modern History of Britain, planned by Lord John Dalberg-Acton, 1st Baron Acton. Dr. Kemp admired Acton’s abilities as a historian, but admitted he had not read any of Acton’s other works; however, he said that he had read this series cover to cover several times, and that the essays in the volumes were written by “really good people.” Dr. Kemp regarded Acton as a “minor hero” since Acton planned the series and solicited the authors.

(photo in public domain)

One of Dr. Kemp’s goals as a professor and as an engineer was to create a contextual work for the history of technology—“real background material for engineers” as he put it—which then did not exist. He also hoped that this area of history would be incorporated into general history survey classes but did not achieve that goal. However, as Dr. Kemp pointed out, history of technology classes are now in the engineering curriculum at WVU, but only as part of the general education requirements. Many of his books on historic structures that date from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were used as part of the effort to incorporate this class into the curriculum. They were also used by Dr. Kemp when he worked on the restoration of the Wheeling Custom House, also known as the West Virginia Independence Hall.

Upon the retirement of Roland P. Davis, Dean of the College of Engineering at WVU, Dr. Kemp acquired some of his published works, as Dean Davis was a noted bridge engineer, and had been an instrumental part of creating the West Virginia State Road Commission in 1919. While many of Dean Davis’ works are in the WVU Library, it only holds two volumes from his personal collection of engineering books; Dr. Kemp has one, as well. It was the practice of the Department of Engineering that, upon the retirement of a faculty member, the books they left behind were put into a big box in the hallway and anyone could choose ones that they wanted—Dr. Kemp said that was how he acquired the works of Dean Davis. Dr. Kemp felt that modern engineers had no use for dated works, but he believed they still had a great deal of value.

The history of religion and theology forms the last section of Dr. Kemp’s collection. Although he donated many of his books in 2016, the donation did not include these volumes, since he was a certified lay speaker in the United Methodist Church and used these books for reference in writing sermons. The donation of his collection to the library, Dr. Kemp felt, was “painful,” as it was almost like “giving yourself away.” While he continued to use many of his remaining books for reference, he regretfully acknowledged that there probably wouldn’t be very many people interested in the books in his donated collection.

Sadly, Dr. Kemp passed away on January 20, 2020, but his recollections as recorded in this oral history will continue to remain a valuable resource for all of us. The books Kemp donated , as well as the oral histories, are part of his collection of papers at the WVRHC.